Mission to Chukotka: What Etta found

The people of Little Diomede in Alaska and Big Diomede in Russia had been trying to arrange reunions for years. In July, Alaska Dispatch News’ Kirsten Swann flew to Chukotka Years to follow along with an expedition, years in the making, that would spend two weeks traveling Russia’s Bering Strait coastline seeking and documenting the shared history across the strait.

(This is the third of three parts. Read parts one and two.)

——-

The northeasternmost community on the Asian continent sits on a narrow strip of land at the cusp of the Arctic Circle, bordered by black rocks and a broad lagoon and the flat, freezing ocean.

In Uelen, Russia, shelter is precious.

The waiting list for government-sponsored housing improvements dates back to the 1970s. More than 10 percent of the population is on it. Extended families share single apartments. There’s no vacant room, let alone hotel.

So when a windswept, waterlogged Alaskan tour group motored up to the beach in early July, there was really only one place to stay: the floor of a vacant classroom at the local ivory carving school, once widely considered to be the best ivory carving school in the world.

It was there, at a crowded workbench on the second floor, Etta Tall met a man who looked just like her uncle. They could’ve been related.

The man at the workbench was master carver Stanislav Nuteventin. He’d heard about Tall’s journey — the expedition up the coast, and the long search for lost relatives with family roots in the Diomede Islands. He shared those same roots.

They embraced. Nuteventin, hands covered in ivory dust, told the curious travelers about his visits to Alaska, his family and his work at the carving school. He talked through an interpreter. Nuteventin spoke little English; Tall spoke little else.

Afterward, she slipped into an empty classroom and wept tears of frustration.

“They don’t understand me; I don’t understand them,” she cried. “It hurts because I lost my language.”

An abandoned village, a fading language

For the people on both sides of the Bering Strait, the years of separation and government intervention have taken a toll.

The day before, during the long ride to Uelen, the expedition pulled ashore at Naukan, an abandoned community some 12 miles south. People from Big Diomede were relocated here by the Soviet Union after the border was closed in 1948. A decade later, Naukan was shuttered; its residents scattered along the coast.

Today, only the bones of the former village remain, home to fearless tribes of ground squirrels and fragrant clumps of Siberian Wormwood. On a clear day, the distant rise of Big Diomede sits framed between two upright whale bones.

Nobody has lived in Naukan for more than half a century. Russians rarely visit. But when the party of tourists pulled ashore that July afternoon, they weren’t alone.

There were others on the beach — a trio of old women and a tall American ethnobotanist named Kevin Jernigan.

The women were born here. They hadn’t been back in decades. Now, they accompanied Jernigan, who came to study the native plants and their traditional uses. “He said Chukotka and Western Alaska share similar flora, from fireweed to the fragrant, abundant wormwood.”

“The similarities went even deeper. Native people on both sides of the Bering Strait shared family connections, cultural ties and traditional practices — but they had their differences, too. They used some of the same plants in different ways. They spoke rainbow varieties of Inupiaq, Chukchi and Yupik. Naukan was more than a village: It was a dialect, too.

“The unfortunate thing is, it will probably be lost,” said Jernigan, standing on the beach beneath the ruins of the old town that July afternoon.

As an ethnobotanist, Jernigan was working to compile a bilingual database of plants and their traditional uses. He hoped to save the knowledge in both Russian and Naukan; preserving the language as well as the culture.

“I don’t want to be pessimistic about it — I mean, the kind of work that I’m doing is supposed to be, of course, to help preserve this knowledge,” he said. “But the thing is, once you get to the point where only the very oldest people speak a language, it’s very hard to save it.”

When Tall’s grandfather Kazingnuk wrote his book, Naukan was a busy Bering Strait trading hub. By the time Tall stepped onto the beach, the deserted buildings were sinking back into the earth; their former occupants long gone.

To find people from Big Diomede, Jernigan told her, look in Lavrentiya.

Traces of Alaska

When the boats slid ashore at Uelen, the surface of the ocean was blindingly bright and smooth like glass. Chunks of waterlogged blubber swayed in the shallows, and stray dogs gnawed on bones along the shoreline. Like every Native community along the Chukotka coast, the town survives on subsistence hunting — walrus and whales.

And like every Native community along the coast, a border guard waited on the beach to check the travelers’ papers. A crowd waited to welcome them.

Uelen is filled with traces of Alaska. A boy on the beach wore a hat embroidered with the word. An old Alaska license plate hangs on a weathered front door. Residents talk about relatives in Kotzebue. Uelen’s celebrated Native dance group sometimes travels to perform there.

Shishmaref is just 100 miles across the water. A century ago, when Uelen was an Arctic trading hub, people came from the Diomedes. Nowadays, only the oldest residents remember, and even the 84-year-old man on the street can no longer recall their names.

Nobody Tall met recognized any of the names from her grandfather’s book.

But finally, after three days in Uelen, she found a clue.

A old dancer named Vladimir knew a man whose parents came from Big Diomede. Pasha Tullun now lives in Lavrentiya, Vladimir said.

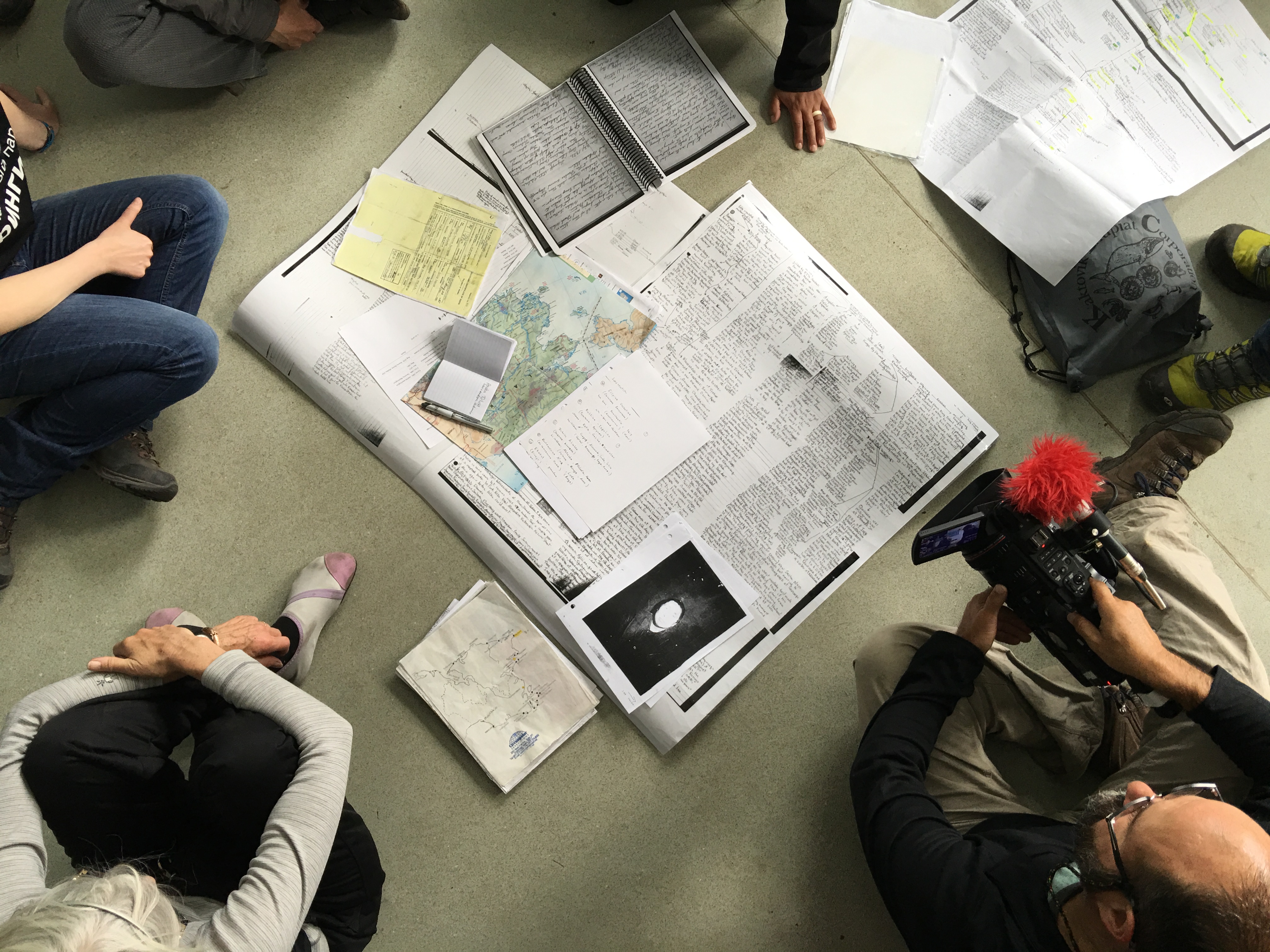

Photo: Looking at a family tree on the floor of the ivory school

He pulled out his cell phone, dialed a number and handed the phone to Tall. The room fell quiet.

“Hello, my name is Etta Tall; my grandpa is Michael Francis Kazingnuk,” she said, while Tandy and the interpreter and Vladimir and the documentary film crew crowded around her in the carving school classroom. “I’m trying to look for my Grandpa Kazingnuk’s relatives.”

The man on the other end of the line spoke a language she’d heard before.

“I don’t understand what you’re trying to tell me,” Tall said.

She listened closely. The words sounded mysterious, yet familiar.

Pasha Tullun was speaking Inupiaq.

Stopped

It seemed like everything was in Lavrentiya. Margarita Gulhih. Pasha Tullun. A museum where Tall hoped to find more clues about the fate of her grandfather’s family

To get there, the expedition made the hours-long boat voyage back to Lorino, then boarded a six-wheel bus to make the rocky overland journey to Lavrentiya the next day. As the shuttle crested the final hill that morning, the city below spilled into view — the air strip, the apartments, the museum.

The bus never made it that far.

Somewhere in the middle of town, the bus stopped to meet a pair of uniformed officers; members of the Federal Security Service or FSB. They came to check permits and passports. Something was missing. In the rush to leave town that morning, the group forgot to carry the special travel permissions mandatory for all movement within a Russian secure border area.

The forgotten papers were found and faxed within 10 minutes, but it was too late. A federal law had been broken. A report had been filed. The FSB officers were not smiling.

Instead of the museum, the bus ferried the tourists to an FSB base at the outskirts of town — a low structure surrounded by a rusting fence, old military vehicles and the wreckage of a dozen other buildings.

Inside, uniformed officers herded the group into some kind of classroom. Oksana Yaschenko, the expedition’s Russian translator and guide, explained the process: Cases were being prepared against every member of the expedition. When the paperwork was complete, every member of the expedition would face a judge. The whole thing would take hours.

One by one, the travelers were escorted to a back office. The decor was sparse: a coat rack, a wall calendar featuring classic cars, a giant map of Chukotka, a bulky desktop computer and printer. A dour Russian officer typed while asking questions through the interpreter.

Back in the conference room, tea was served — Lipton yellow label, flavorless gingersnaps and chocolate. A few books of Chukotka photography and history were distributed around the conference room. Then an officer procured a pen.

Sign it, please, they said, gesturing to the coffee table book with the thick glossy pages.

Write about your experiences in Chukotka so far.

Then it was time for lunch, and the group was unceremoniously released back onto the bus for a leisurely stop at the local cantina.

That’s where Tall met Tullun.

He had been notified of the group’s predicament, and agreed to accompany Tall back to the headquarters where the group was detained, just so they could talk. The officers agreed to let him.

Huddled around the desk in the FSB conference room, guards watching, Tall showed Tullun her grandfather’s book. He spoke to her in Russian and Inupiaq. Could he be one of those distant relatives for whom she’d been searching? Oksana was gone, busy translating for the officer and the tourists in the back office, but the FSB guard helped translate where he could.

Tall spoke little Inupiaq. As a child on Little Diomede, she heard Inupiaq at home but English at school. Eventually, the Inupiaq words had all but faded from memory. Today, only about 22 percent of Alaska’s Inupiat people still speak the language, according to the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

When Tullun spoke, Tall could not understand.

Before long, it was time to face the judge. Tall and Tullun parted ways on the courthouse steps, sharing one last quick embrace, and the group filed through a metal detector and into a tiny lobby. One by one, the travelers were summoned into the courtroom. One by one they emerged with sealed paperwork detailing their ultimate punishment: A fine of about $8.20.

By the time the final hearing ending, well past 3 a.m., there was nothing to do but tumble back into the bus, bleary-eyed and exhausted, for the return drive to Lorino.

Back to Lorino

That night, Tall dreamed they were chased by a bear and its cubs. In her dream, a Native man came to save them — but someone killed him before he could.

What did it mean? The next morning, those thoughts weighed heavy on her mind. She felt nauseated.

She wondered: Should she stay in Lorino or try and go back to Lavrentiya? Should she give them her book like she’d planned? Would they even understand it?

“Will it help them, like it helped me to be strong?” she wondered. “I think about the young people: Do they care about their history?”

In the end, she decided to stay. The journey back to Lavrentiya was too long, the results too uncertain. And she felt a kinship with the people in Lorino.

They are marine mammal hunters, like the people from the Diomede. Every summer, the Lorino hunters’ collective fills a quota of 56 whales and some 300 walrus, just enough to feed the community for another year. The leftover bits and pieces feed the local dog teams and strays.

In 2014, Chukotka whalers struck 124 gray whales total, according to International Whaling Commission records. Alaska whalers, with a quota for bowhead, struck 53.

What she found

From Lorino, it was a choppy, picturesque boat ride to a quiet bay; then an ambling sunset bus ride across boulder fields to Novoye Chapolino; then a slow journey back up the winding, rocky road to Provideniya, where the tourists would await the Bering Air flight back to Nome.

On the last night in town, the women in the expedition gathered for a visit to the local banya, where the beaming proprietress proffered slippers and sauna caps. Russian music videos blared from a television set on the wall. Between steams, the women sipped strawberry juice and ginger tea.

Afterward, they walked back to the apartments through the fog, stopping at the local market to buy sticky vanilla ice cream bars. The Provideniya streets were quiet and still.

Back in the apartment, Tall scrolled through her phone, looking at all the memories she’d collected over the past few weeks.

Videos of the boat ride up the coast. Selfies with elders in Lorino and children in Uelen and people up and down the long Bering Strait coast. She struggled to remember their names. Maybe Tandy Wallack would find a way to hold a reunion on Big Diomede. Maybe she would see them again.

“I told them to add me on Facebook,” she said.

Her grandfather’s book sat tucked into her bag, ready for the flight home. She never found Kazingnuk’s relatives. She found something else instead.

“I feel relief — a release,” Tall said. “Maybe I don’t have to wonder anymore.”

PREVIOUSLY:

Kirsten Swann is a journalist living in Anchorage. She writes for Alaska Dispatch News’ 61° North magazine and ShowMeAlaska.net.