Fossil fjords in Africa hold clues to how the Arctic could look in a distant future

Ancient dried up fjords in Namibia and modern northern fjords formed under similar conditions, but hundreds of thousands of years apart.

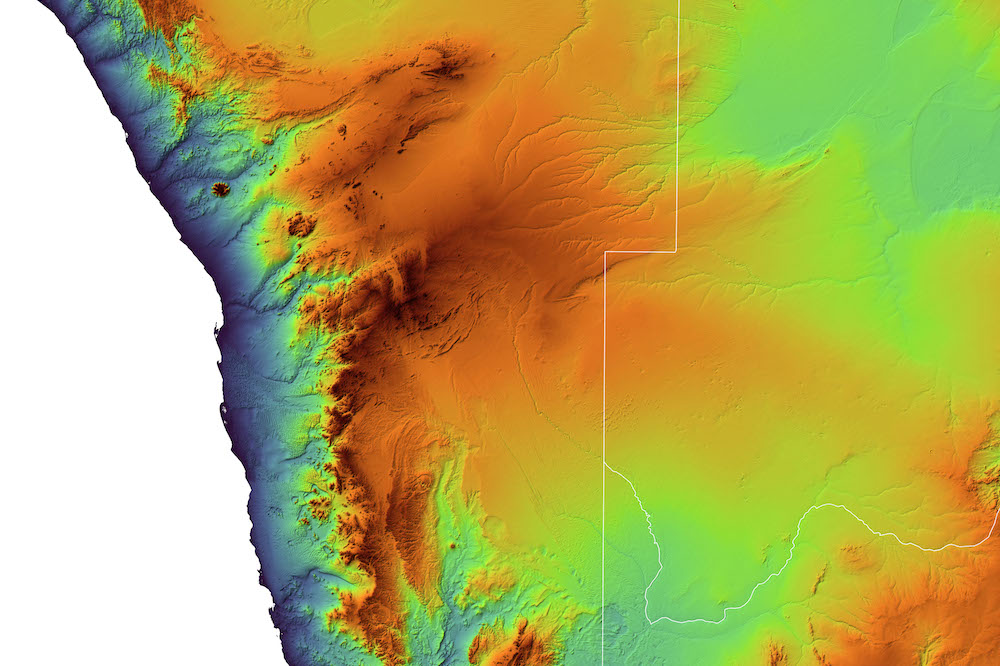

Unless you are Namibian, the image above may, at first glance, appear to be yet another satellite image of a fjord-cracked northern coastline — perhaps Greenland or Norway.

The close similarities in appearance aren’t just a coincidence; Namibia holds a network of fossil fjords that could help climate scientists better understand the climate of the past while also offering insights into the role modern fjords play in a warmer world, suggest the authors of a recent scientific paper.

And they can give us some hints about how Arctic fjords may end up looking in a distant future.

Subtropical Namibia would seem an unlikely place to find a landscape carved by glaciers, but its climate has not always been that way. Some 300 million years ago, during a period known as the Late Paleozoic icehouse, much of the landmass that today is Africa was close to the southern pole, where it was covered by an ice sheet measuring 1.7 kilometers (slightly more than 1 mile) thick.

As this ice moved, it carved long narrow valleys. When the climate warmed, the ice sheet was first reduced to isolated glaciers some 100 meters thick before disappearing entirely. As they shrunk, the valleys served the outlet for meltwater. When they melting was complete, the valleys were filled with seawater and formed fjords.

Then, as now, fjords serve as major carbon sink. Modern fjords, which formed around 12,000 years ago, may contain more than 10 percent of the world’s buried carbon, despite accounting for just 0.1 percent of the world’s oceans. By acting in the same way, fjords of the past probably played a key role in climate regulation, according to the paper’s lead author, Pierre Dietrich of the University of Rennes.

Namibia’s fossil fjords are believed to have acted in the same way as modern fjords in the North. And while fjords in places like Greenland and Norway may be much larger, their appearance is the same as those in Namibia, reflecting the similar ways in which they were formed.

Geologists have long assumed that fjords and other geological features formed by glaciers were transient — that over a relatively short span of time on a geological scale, they would be eroded or collapse. That Namibia’s remain standing suggest that northern fjords may do so, too.

The most likely reason Namibia’s fjords did not disappear is because as the waters of the prehistoric fjords retreated, sediment began to build up. Initially, that protected them. Over time the sediment has been eroded, exposing the walls of the now dried out fjords.

Thanks to their similarity and their relatively pristine state, Dietrich reckons, it is likely that Namibia’s fjords can help modern scientists understand what happened as the Late Paleozoic icehouse period came to an end and a warmer climate took hold (icehouse periods mark the end of a cooler period during Earth’s history, and, as it happens, is its current stage).