With glacial melt accelerating, a geoengineering movement gathers momentum

More scientists are seriously proposing geoengineering as our best bet to slow the contributions of glaciers to sea-level rise.

Resorting to geoengineering, taking steps to purposely alter the Earth’s climate, to address the effects of a changing climate, is an old idea, dating as far back as the 1980s, when James Early, of The United States’ Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, suggested placing what amounted to a translucent cosmic parasol between the Earth and the sun.

To date, most of the ideas put forward are variants of the same idea and count on blocking some of the sun’s energy to stunt temperature rises.

Such projects are typically deemed as expensive as they are outlandish. But if cooling the planet isn’t economically feasible, temporarily stopping one of its most damaging impacts may be. Or so says an increasing number of scientists who now seriously propose using geoengineering to stop polar glaciers from sliding into the ocean and contributing to sea-level rise.

In commentary published by Nature, a leading journal, this week, four scientists argue that geoengineering is a cost-effective measure that would stave off sea-level rise “for centuries,” buying time to address the root causes of their melting.

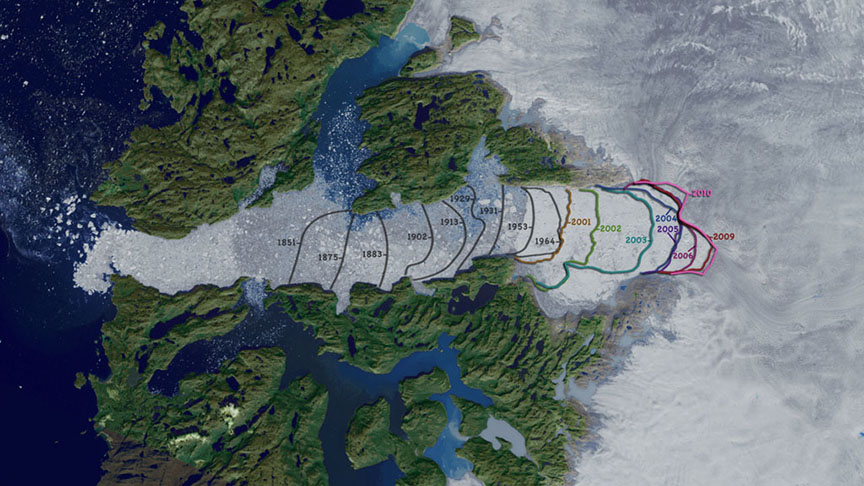

“In our view,” they write, “this is plausible because about 90 percent of ice flowing to the sea from the Antarctic ice sheet, and about half of that lost from Greenland travels in narrow, fast ice streams. These streams measure tens of kilometers or less across. Fast glaciers slide on a film of water or wet sediment. Stemming the largest flows would allow the ice sheets to thicken, slowing or even reversing their contribution to sea-level rise.”

[As Arctic warms, interest in geoengineering increases]

To be sure, such megaprojects would not be cheap, but the authors suggest they would be comparable to less noble megaprojects that have already been completed. Building artificial islands and hydroelectric dams have had price-tags in the tens of billions, for example. The cost of cleaning up after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill is estimated at $65 billion.

As shocking as that is, the alternatives, they point out, are dearer yet. Preventing flooding through sea-walls and the like would cost tens of billions of dollars annually. Not doing anything has an even higher price: an estimated $50 trillion annually in infrastructure damage, societal disruption and human displacement.

“Just a few very fast flowing glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica drain much of the ice sheets, and will be the route for ice that will raise sea levels. These glaciers are tens of kilometers across, and so attractive targets to stabilize rather than building walls around the world’s coastline,” said John Moore, a research professor at Finland’s University of Lapland and the chief scientist at Beijing Normal University.

Glaciers can be slowed in one of three ways, proponents reckon: prevent warm ocean water from reaching their bases and melting them from underneath; use artificial islands to support ice shelves, where glaciers protrude over water; or deny glaciers the water that allows them to slide by draining the glacial beds they sit on.

[So much water pulsed through a melting glacier that it warped the Earth’s crust]

This last may be particularly effective since fast-moving ice streams supply 90 percent of ice entering the sea. As a glacier slides over the ground underneath it, the friction generates heat. The ice this heat melts makes up 90 percent of the water at the base of the ice streams.

Now sitting on a lubricant, the glacier begins a cycle that sees it move faster, generating even more heat, creating more water, which increases the rate of movement further.

In the past, technological fixes to human-induced global warming, including a plan to spray water on Antarctica’s ice, have been debunked as ineffective, and possibly even counter-productive. Others chafe at the idea of doing something that enables the behaviour that changes the climate in the first place.

However, that has not stopped various ideas for preventing glaciers from melting from emerging in recent years. Most involve covering ice in some manner to prevent it from being melted by the sun’s energy.

[A climate chain reaction: Major Greenland melting could devastate crops in Africa]

Whether covering glaciers or stopping them from moving, both are inspired by natural processes, say proponents. Snow and clouds reflect the sun. Glaciers, meanwhile, have occasionally been observed slowing or even stopping their forward progress.

And, since preventing glacial melting focuses on the symptom, and only temporarily, humans, the authors note, are not off the hook entirely.

“Geoengineering of glaciers will not mitigate global warming from greenhouse gases,” the authors write. They also suggest that if carbon pollution increases unchecked, their proposal may only be an exercise in “managed collapse,” rather than a rescue effort.

Regardless of how much momentum the idea has gained, it may still meet immovable objects. Economics is one. Technical and political considerations are two others. Antarctica, for example, is governed in concert by 53 countries. Getting them to agree on the details of such a massive undertaking would take irresistible argumentation.