Harsh climate: The struggle to track global sea level rise

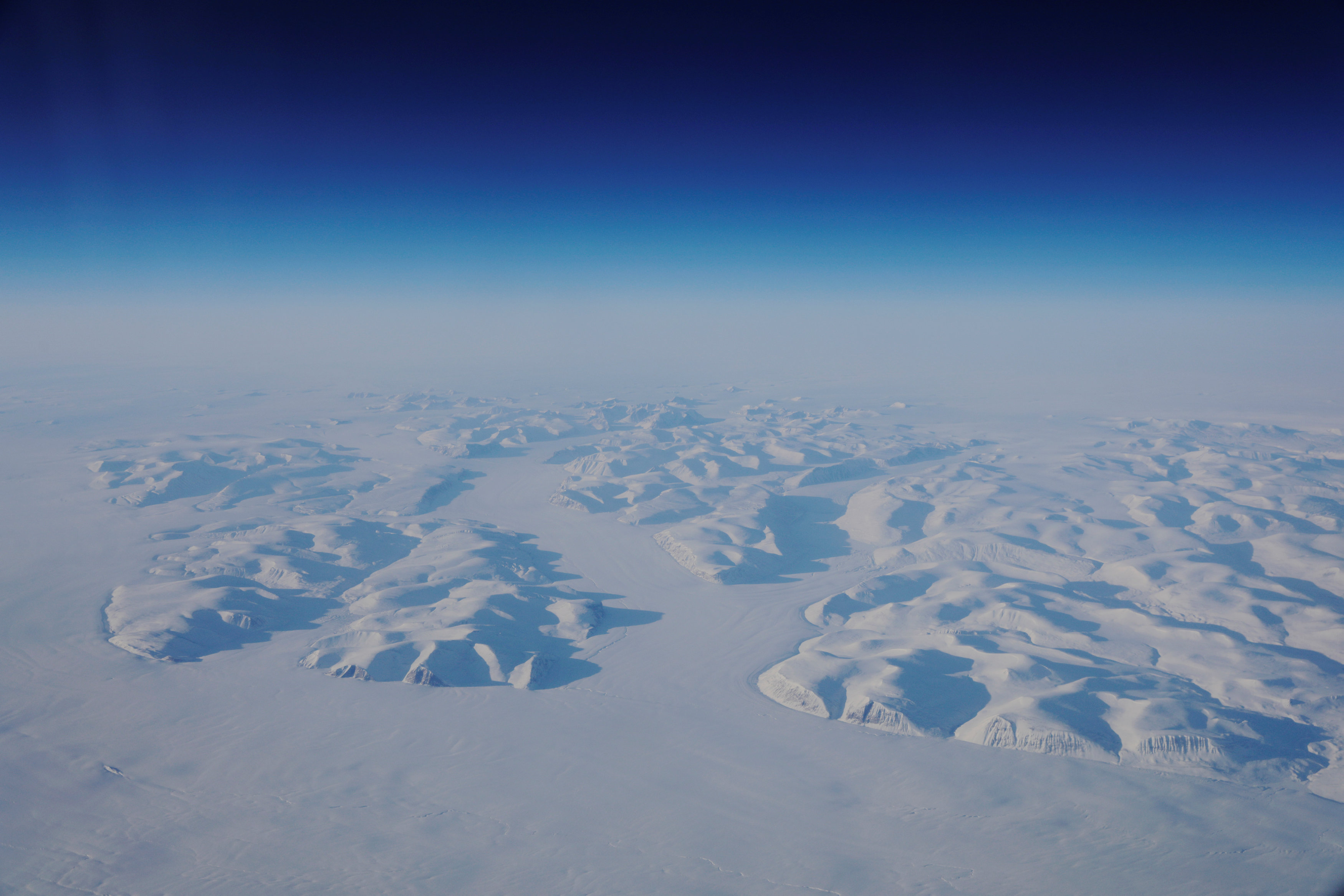

Researchers go to great lengths to better understanding what's happening to Greenland's ice cap and glaciers.

A loud rumble jolted climate scientist David Holland just before he went to sleep inside his fiberglass bear-resistant dome, set up next to a frozen fjord in Greenland. He scrambled outside into the sunlit night at about 11 p.m.

The thundering sound grew louder as he watched a chunk of ice about a third the size of Manhattan break away from the Helheim glacier. Over the next half hour, the iceberg cracked into pieces and tumbled into the water — a mesmerizing sighting of the sea level rise that Holland has devoted years to studying.

Such major glacial ruptures, known as calvings, are rarely observed in person. A Reuters photographer captured the event on video as Holland, a New York University oceanographer, took in the “absolutely breathtaking” scene.

“It’s just amazing how beautiful nature is, how violent and unstoppable; it just does its own thing,” he said. “We actually saw the process by which sea level rises from glaciers.”

Now Holland and other climate scientists just have to figure out how — and how fast — warming oceans are undermining the glaciers of Greenland and Antarctica. The best predictions for sea-level rise this century are getting more dire, and yet less precise, in part because of a lack of understanding of these glaciers and how their behavior fits into global climate modeling.

A key obstacle to producing better predictions is the extreme difficulty of the research, which requires dangerous field work in some of the world’s harshest terrain.

Researchers must contend with winds strong enough to sweep away bolted-down equipment; temperatures that can freeze skin on contact; and remote locations that make securing supplies a steep challenge.

Security teams help scientists avoid falling into hidden crevasses, and, in the Arctic, teams arm themselves with rifles and sleep in fiberglass shelters to avoid becoming a meal for polar bears.

The challenges of data collection also require a host of creative solutions that scientists are refining through trial and error. A NASA team that is now three years into a five-year, $30 million project called Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) has used radar to map changes in the sheet’s ice loss over time by returning each year to fly the same precise path; dropped probes from planes to measure water temperature and salinity at various depths; and mounted sonar instruments to ships to map the topography of the ocean floor.

The difficulties and dangers in accessing the ice-choked waters near Greenland’s glaciers caused some researchers to enlist the help of local wildlife by tagging seals, halibut or narwhals with sensors to gather data.

NASA researchers and Holland are focused on Greenland because it currently contributes more to sea level rise than the colder region of Antarctica — and because the research is so much harder in the Antarctic, with its punishing climate, massive scale and logistical challenges.

“It’s mind-boggling how difficult it is to do things in Antarctica,” said Holland, who has conducted studies in both regions. “Work that can be done here in Greenland on the scale of summer takes five to ten years to set up and accomplish in Antarctica.”

A $20,000 bolt

Scientists worry that the calving process underway at Helheim — named for the Vikings’ world of the dead — provides a preview of what might happen in Antarctica on a larger scale. Another Greenland glacier called Jakobshavn has seen similar calving events.

In both polar regions, field researchers face serious hazards. Bad weather can strand researchers for weeks and hidden dangers can lurk beneath the snow. In 2016, Holland’s colleague Gordon Hamilton, a U.S. climate scientist, was killed in Antarctica when his snowmobile plunged into a crevasse.

The job of keeping Holland’s team safe belongs to Brian Rougeux, a former mountaineering guide who has worked in both polar regions. Rougeux, who originally met Holland in 2010 in Antarctica, where Holland was servicing weather stations, said sudden changes in weather and visibility in Antarctica can sometimes be life-threatening.

“You’re trying to navigate to a tent in the middle of half a million square miles of flat white, with no real terrain features,” Rougeux said.

GPS can help, but could lead teams into areas with hidden crevasses.

Preparation is key to efficiency as well as safety.

“Going back to town to get a particular bolt takes $20,000 of helicopter time, so it becomes a pretty expensive bolt,” Holland said.

The research challenges often persist after researchers return home from the field. The data-gathering tools they leave in place — from moorings that monitor oscillating water temperatures to radars encased in 10-foot-tall, egg-like protective shells that take images of melting ice — are vulnerable to the elements. A buoy collecting ocean data for Holland’s team in Greenland was swept away by powerful currents and eventually surfaced on a beach in Scotland, and powerful winds swept away other equipment they had bolted in place.

Help from the locals

Sometimes conditions are so brutal that researchers need to enlist the experts: local wildlife.

In the Ilulissat fjord in western Greenland, Holland’s team uses native ringed seals fitted with sensors to record depth, temperature, and salinity year-round near the Jakobshavn, the island’s fast-flowing river of ice. They relied on seals because it was too dangerous to pilot a boat through the icy waterway near the glacier, which is believed to have produced the iceberg that sank the Titanic.

“It is difficult to find a way that a robot made by an engineer could do anything similar to what a seal can do,” said Holland.

Holland had teamed up with a local seal biologist, Aqqalu Rosing-Asvid, a former hunter and fisherman. In 2010, they camped out on Greenland’s west coast for a week, but caught no seals. It was not until their next attempt two years later that they finally tagged their first seal.

They also use halibut because their deeper swimming helps monitor the water column nearest the seafloor. The team only tagged fish caught during the warmest days of the fishing season to prevent their eyes from immediately freezing in the cold.

The team relies on fishermen to retrieve the data: Rosing-Asvid’s phone number is on the fish tags. “The fishermen call me on the phone, and we arrange to send the tag here,” he explained.

Last year, three out of the 20 halibut sensors made it back.

Another animal pressed into research in the Arctic is the narwhal, an elusive whale with a tusk protruding from the male’s head. Marine biologist Kristin Laidre, of the Polar Science Center at the University of Washington, has in the past netted narwhals in order to pin a satellite tag to their dorsal ridge “like an earring.”

Laidre shared the narwhals’ depth, temperature and salinity readings with the NASA team, important because warmer, saltier Atlantic waters tend to sit below colder, fresher waters off the coast of Greenland. Glaciers connected to the deeper waters are melting at faster rates.

“Even today, there are some places where we still don’t know how deep the water is,” said Josh Willis, lead scientist for NASA’s OMG project. The tagging “gives us an idea that the water in some spots is at least as deep as a nearby narwhal dive.”

Reporting by Lucas Jackson in Greenland and Elizabeth Culliford in New York.