Swedish supreme court decision upholds Sámi claims in a key land-rights case

The decision is limited to a specific swath of land, but could set a precedent for cases elsewhere.

An association of Sámi reindeer herders in Sweden has successfully argued that its historic connection to a huge grazing area south of the city of Kiruna gives it the exclusive right to manage hunting and fishing there.

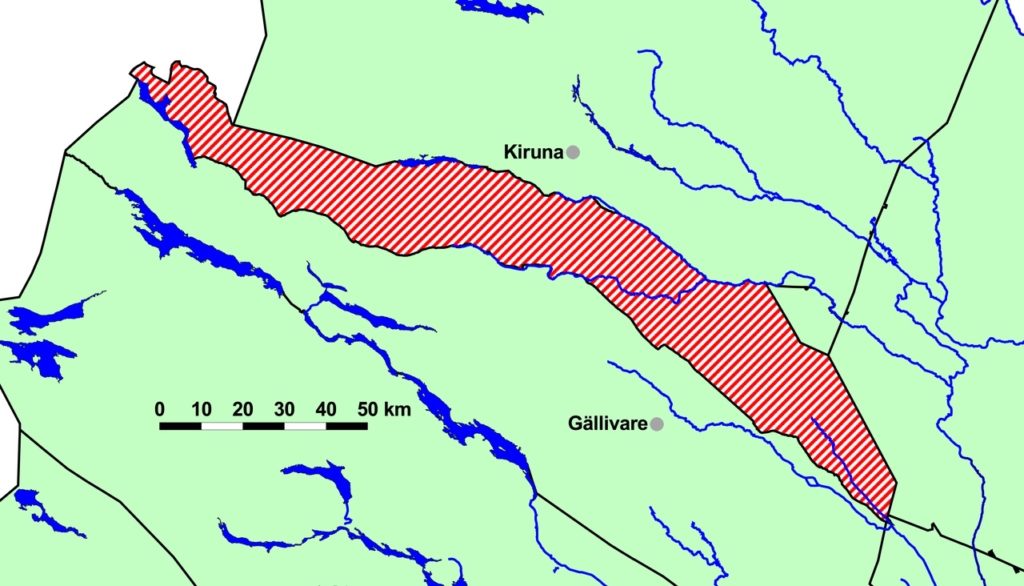

The decision, handed down by the Swedish supreme court on Thursday, applies solely to the 2,000-square-mile (5,000-square-kilometer) tongue of land extending from the Norwegian border known as Girjas Sameby, but Sámi groups hope it can be used as a precedent in other cases challenging state authority over traditional lands.

Justice Sten Andersson said the decision took into account Girjas Sameby’s sparse population and “special situation,” but he underscored that it was in line with the rulings on previous cases involving land-use disputes.

The ruling is the final say in a legal battle that got underway in 2009 when Girjas Sameby and SSR, a national group representing Sámi associations, challenged a 1993 reform of hunting regulations that transferred responsibility for granting permits to the state.

A central question of the trial had been the meaning of “time immemorial” and whether the term could be used to uphold land claims. The court found they could.

“Rights that emerged in the past based on traditional use do not come to an end,” Andersson said. “Yes, Girjas Sameby has the right to regulate hunting and fishing because of its traditional rights.”

Although the court said there were holes in the Sámi documentation for how the area in question had been used in the past and when they first began using it, historical documentation of past land-use in other parts of Sápmi used had been permitted as evidence to support Girjas Sameby’s claim.

“That allowed to make some reasonable assumptions,” Andersson said, “and, based on that, the court could conclude that the Sámi’s rights in this specific area date back to at least the mid-eighteenth century.”

The state had argued throughout that its own authority stemmed from its ownership of the land, which it traces back to the nineteenth century. While the court admitted that this was clearly documented, it found that the documentation showed that the crown had accepted the Sámi’s exclusive right to hunt and fish there, and that with that exclusivity also came the right to authorize hunting and fishing by others.

That right, it had found, had been taken away by the 1993 reform.

The decision is in line with lower court rulings that initially found that the Sámi had an exclusive right to hunting and fishing, but which was later partially overturned by a higher court ruling ordering the two parties to share authority.