How an Alaska professor’s pop-up book aims to spread awareness of marine plastic pollution

The Alaska-themed “Our Plastic Ocean” explains the problem of plastic pollution in northern waters, and is paired with “Our Clean Ocean,” which offers solutions.

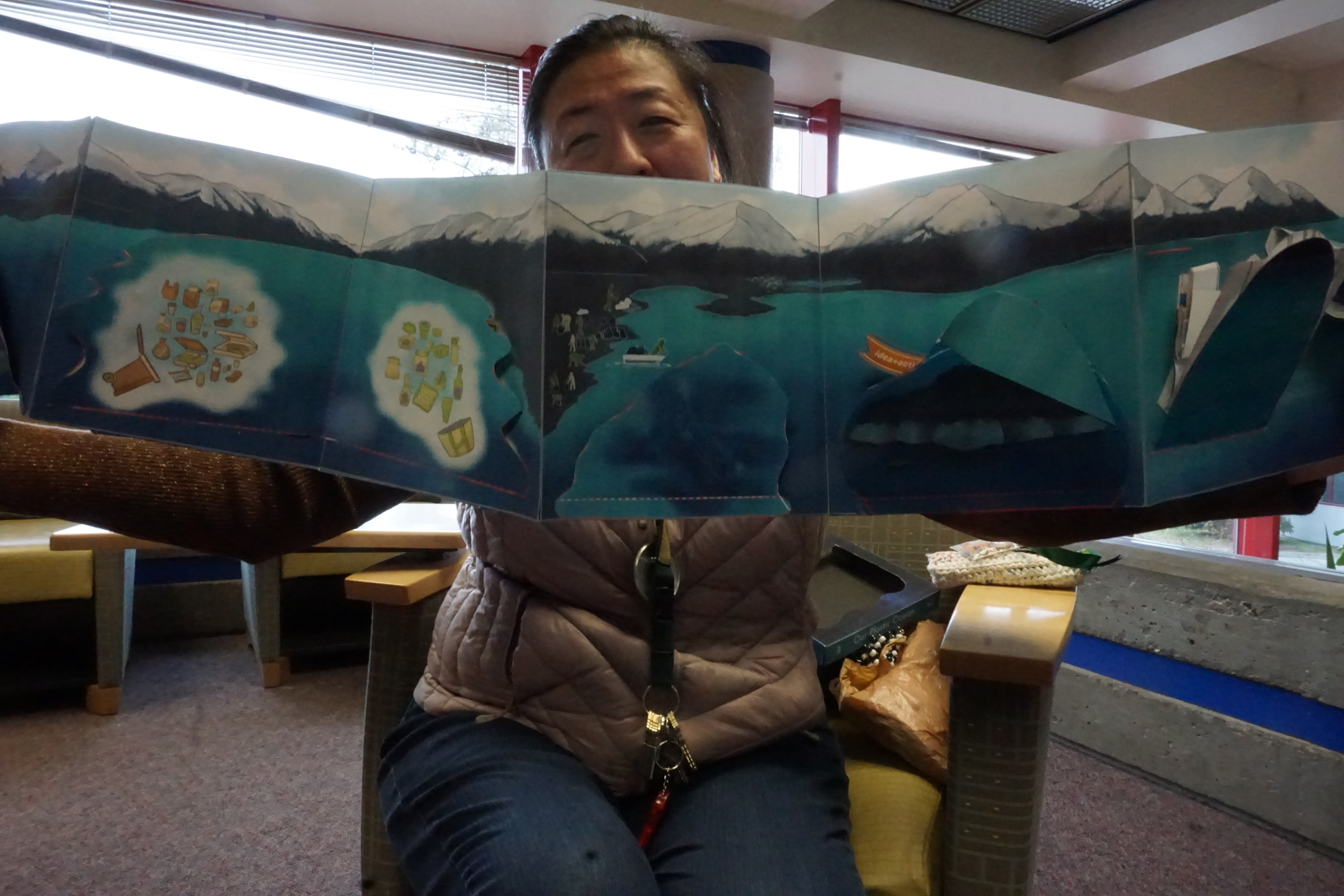

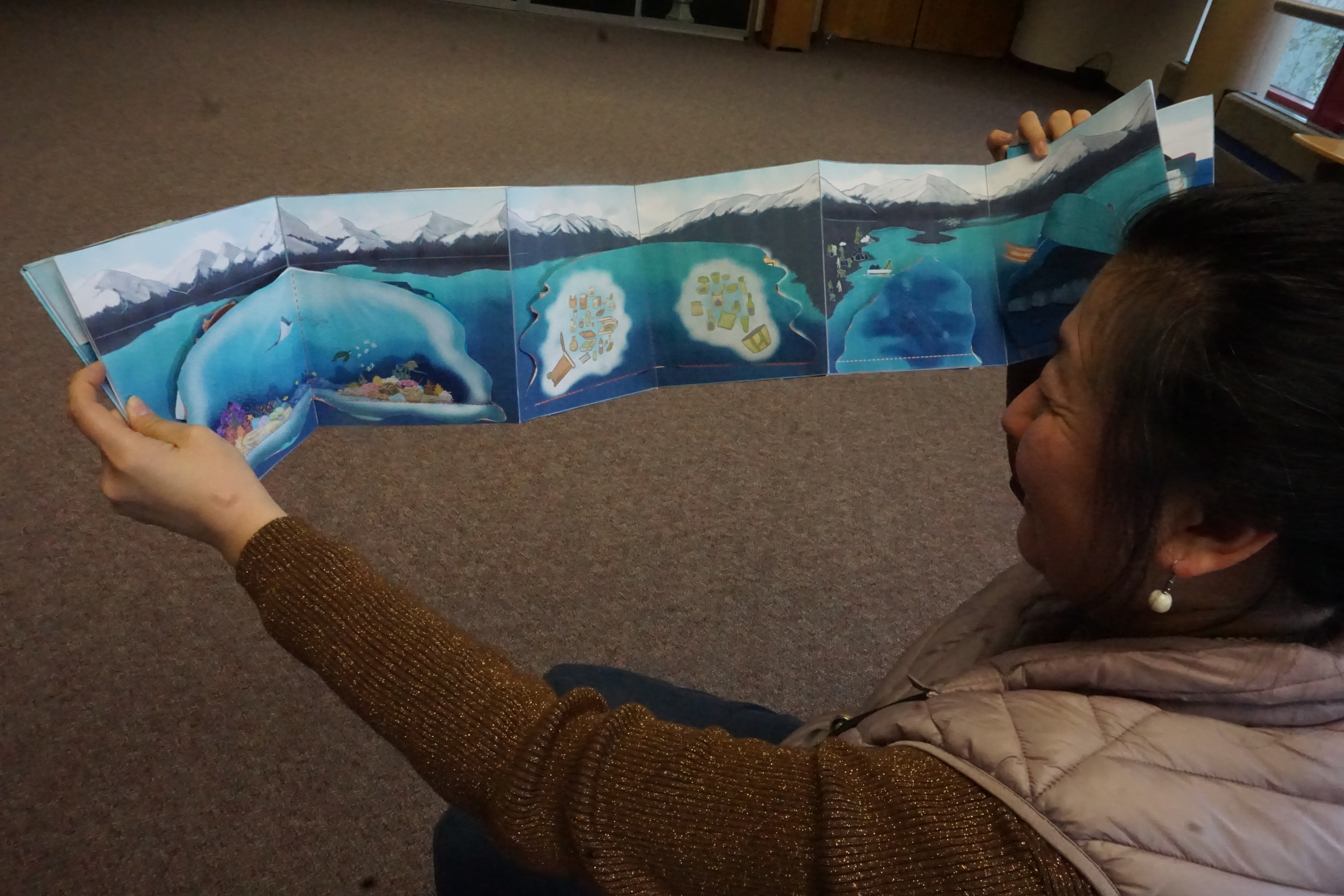

An Alaska art professor’s concern about the marine environment has combined with her passion for pop-up books to produce a colorful three-dimensional tool to educate children about the problems of marine plastics.

Herminia Din, a professor of art education at the University of Alaska Anchorage, has created an Alaska-themed pop-up book titled “Our Plastic Ocean.”

It shows, from page to page, how human activities produce trash that goes from land to the sea and how, once the plastic trash is in the water, it breaks down into small pieces that are eaten by marine creatures and wind up inside the fish that people eat.

“I feel like it’s a public health matter. I feel like it’s to that point. Serious,” she said. “The plastic will not dissolve. It will just break down from visible to invisible.”

The book’s message is not all gloom and doom.

To find the solution to plastic pollution, readers can flip it over and see another version, titled “Our Clean Ocean.” There they see, in pop-up form, the steps to take to keep plastics out of the water — steps like switching to cloth bags and reusable cups, recycling more waste and using less disposable packaging that creates waste.

The book is still in mock-up form and not yet published. Copies will be printed later this year and are expected to be available for sale at the end of summer or early in the fall.

For Din, the book is part of a years-long campaign to bring attention to marine plastics in Far North waters — a problem that’s only gained widespread recognition in recent years, and still surprises some people.

“Everybody thinks that we are so clean and so fresh, nothing being polluted. No. That’s not the case at all,” she said.

Plastics, often in tiny pieces, accumulate in the Arctic because of the way ocean currents flow north, carrying trash deposited from far away. New research has found that Arctic sea ice traps and transports microplastics, the tiny pieces of plastic that are birds and fish can mistake for food. The Arctic Council has identified plastics pollution as a problem that demands and international response, and an action plan is in the works.

Din got firsthand looks at the problem when she visited coastal towns in Norway and villages in Alaska.

She visited Norway through here connections with the University of the Arctic; the consortium of northern institutions has a network focused specifically on Arctic plastic pollution and on sustainable art. In Norway, where she was a visiting art educator, communities are right on the beaches, making debris more accessible for examination and cleanup — and more obvious.

But in vast and sparsely populated Alaska, where much of the trash washes up in remote areas, awareness about and cleanup of marine debris can be more complicated.

In communities like Anchorage, where Din lives, and Nanwalek and Port Graham, Alutiiq villages in the Gulf of Alaska that she visited last year, waters are fairly sheltered from external currents, meaning most of the plastics pollution is locally generated. That includes the “ghost owls,” the local kids’ term for plastic grocery bags that are whipped around by the wind, she said.

In sites that have exposed ocean beaches, though, there are stunning loads of plastic coming in from faraway places, she said.

An eye-opening experience was her trip last fall to St. Paul Island in the eastern Bering Sea. There, Din served as an artist in residence during the community’s Bering Sea Days educational program, and she split her time between creating art projects at the school and working with the children to clean up beaches, at times translating the Chinese characters that were on pieces of long-distance-traveling marine debris.

Din also helped encourage some changes in daily practices on the island. The large amount of superfluous plastic packaging that was being used for school lunches, from Styrofoam containers to the plastic-wrapped packages of plastic utensils, was “one thing that shocked me the most,” she said. Students, teachers and parents came up with a response — they are using forks and spoons brought from home and washed in the school’s home-economics classroom.

Din’s practices what she preaches. She carries in her handbag a set of flatware, a collapsible and washable tea cup and a reusable shipping tote, all within convenient reach if she needs them.

The pop-up book and other plastics projects grow out of Din’s long experience blending environmental stewardship with art.

At UAA, she has promoted “Junk to Funk” projects that helped students convert items as large as used car parts, which can become furniture, to scrap paper, which can be rolled into beads used for jewelry. With inspiration from Scandinavia, she has also helped manage an outdoor Winter Design Project, using the UAA campus as a setting for temporary art pieces like snow sculptures and ice etchings.