How an art project works to bring Arctic climate change to a global audience

Photographers and videographers of the Arctic Arts Project bring scientific research to life by capturing compelling images of a changing North.

Scientists have been studying climate change in the Arctic for decades, and countless studies have quantified the wide-ranging effects of changes in the region upon the globe.

But for many people located outside the North, it’s difficult to visualize these changes — and to bring them close to their own lives.

That’s where art and photography can help.

Kerry Koepping, the founding director of the nonprofit Arctic Arts Project, works with visual artists to show how rapidly the Arctic is changing — and to spur action from people around the world. The photographers and videographers who collaborate on the project include Andrea Sparrow, Carsten Egevang, Joshua Holko and others.

Climate Chaos: The Permafrost Quota from Arctic Arts Project on Vimeo.

Koepping first conceived of the project about a decade ago. He was photographing the foothills of Denali, and he noticed strange hummocks, shaped like polygons, scattered across the tundra. He soon learned that they were formed by permafrost thaw, and he realized that the visually arresting images he’d captured could illustrate important scientific phenomena. It was, he told ArcticToday, his “first realization that art could communicate something that even science couldn’t communicate at that point in time.”

Arctic Arts now works closely with scientific researchers to bring their work to life.

In March, for example, Jason Box and other researchers published a meta-study gathering 35 years of data on climate change in Greenland — from temperature increases to sea ice loss, from shifts in the tundra to land ice loss.

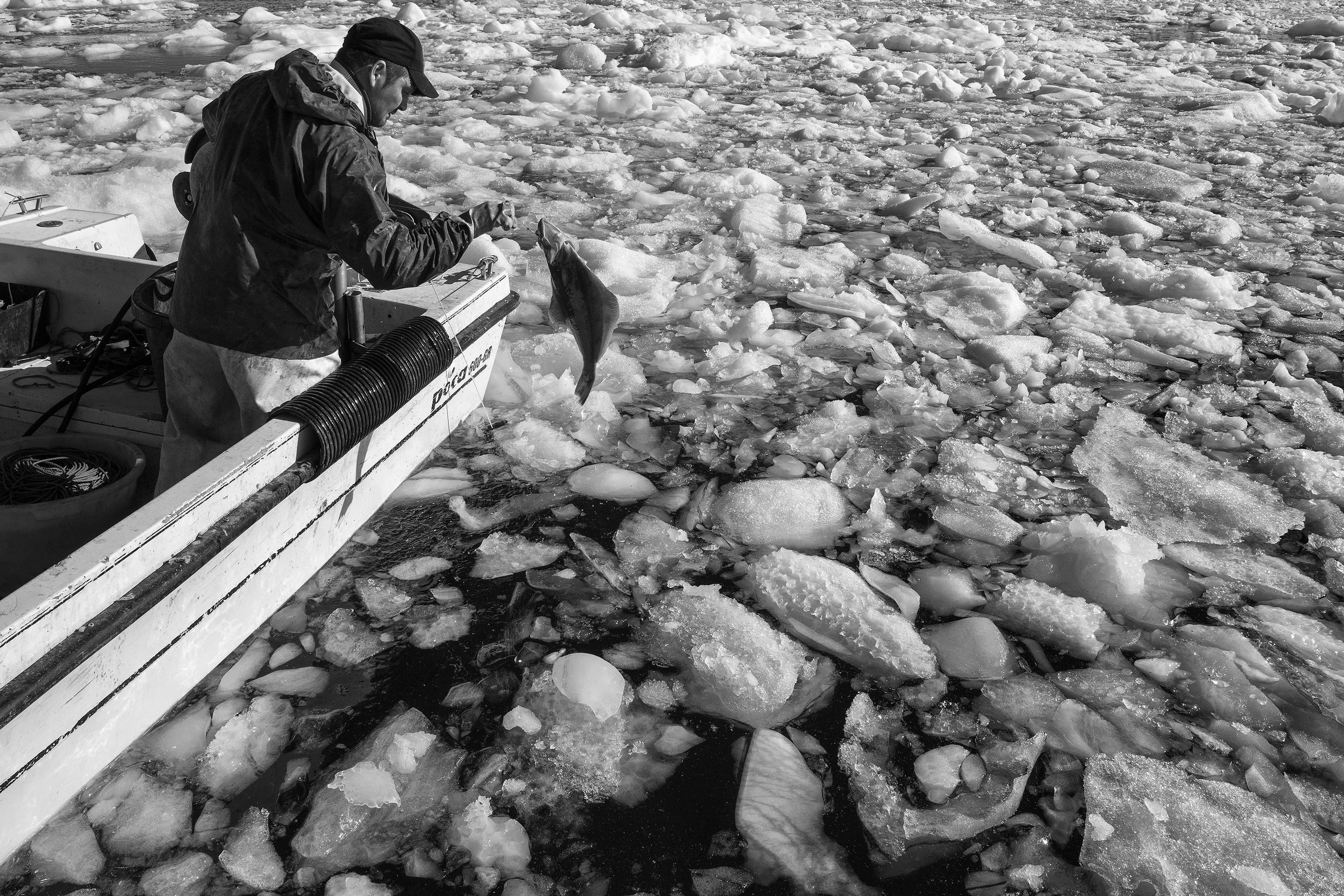

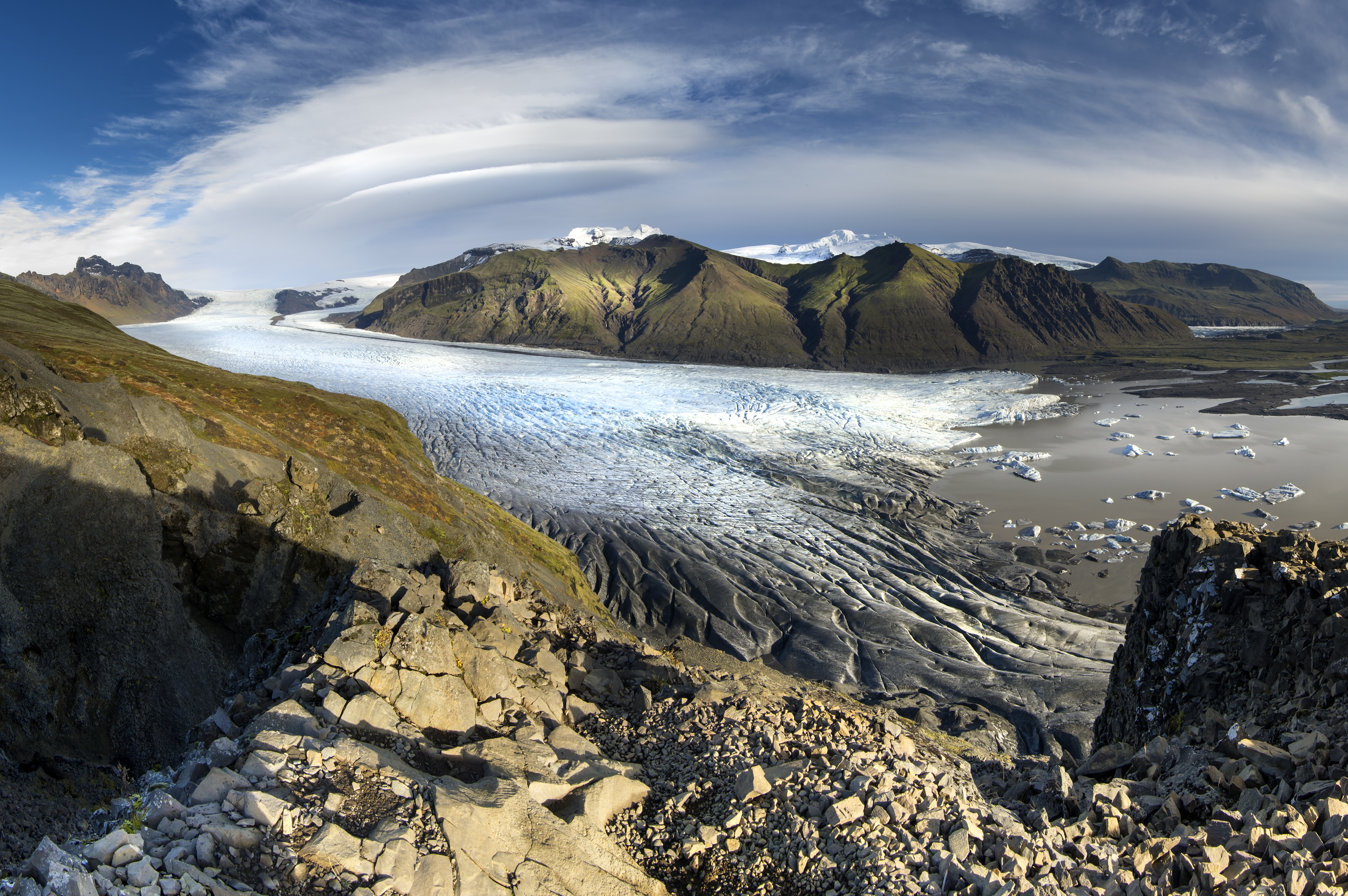

Two months later, in May, Arctic Arts photographers and videographers traveled to Greenland to see exactly how those changes are playing out in real time. They captured images of early flora bloom, of dissolving sea ice, of glacial runoff and flow. They also compared photographs they’d taken just two years earlier of the Eqi glacier and found it significantly reduced in that short period of time. They could already tell that this summer would see unprecedented change in the Greenland ice sheet — and it was all backed by long-term trends in research.

“The whole impetus of the project is to drive a visual reference on the science of climate change,” Koepping said. “To give people an understanding, visually, of what is happening on a global basis and how it’s relevant to their own lives.” Even those who are already interested in how climate change is reshaping the planet may find the science overwhelming, he said.

The nonprofit, which is mainly funded by donations from corporations and private individuals, is based in Boulder, Colorado. It’s part of the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAR) at the University of Colorado.

“We’re fortunate being based here, that we have these great scientific minds to draw from. And they’ll come to us and say, you know, we have no visuals on x, y, z,” Koepping said. The nonprofit now has an archive of 140,000 photos and videos of the changing Arctic. The images can be used for everything from publication in national outlets to helping scientists further their own research.

“That’s really been the joy of the last few years, is teaching scientists how to communicate what they do,” Koepping said. “It’s not just about creating data, it’s about what we do with the data that means something to people around the world.”

In June, Andrea Sparrow presented many of the project’s dramatic images on climate change in Greenland at the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, and the visual artists hope that their work will continue to reach audiences at events and to be used in educational materials.

Next, Koepping is headed back to Greenland to capture this year’s dramatic changes, while Sparrow is following researchers from Toolik Station to document Alaska’s record-hot summer.

“The key is to tie those visuals directly to the science,” Koepping said, “and then directly correlate them to people’s lives individually.”

“What can somebody do that will make a difference?”