How an Inuit approach to cancer care in Canada promotes self-determination and reconciliation

"People need to know that they are not alone.”

For thousands of years, Inuit have adapted to the changes in their environment, and continue to find new and innovative ways to survive.

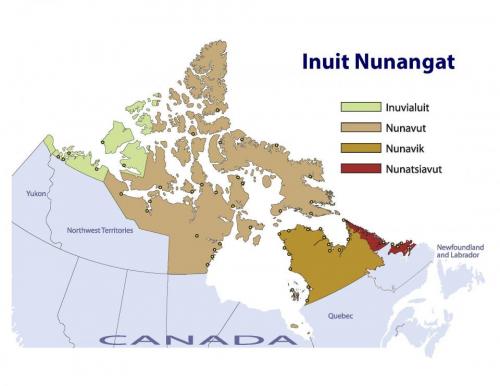

But life expectancy among populations in Inuit Nunangat (the traditional territory of Inuit in Canada) is an average of 10 years less than that of the general Canadian population.

Cancer is a leading cause of this disparity. Inuit experience the highest mortality rates from lung cancer in the world, and mortality rates of some other cancers continue to increase disproportionately.

Inuit communities tend to be self-reliant and are renowned for working together for a common goal, which is evident in their self-governance and decision-making activities. They have also endured a long history of cultural insensitivity and negative health care experiences that span generations.

[Read more: More than one in 100 Nunavut infants have TB]

The ways the Canadian health care system interacts with Inuit populations plays an important part in this health disparity. And there is an urgent need for Inuit to be able to access and receive appropriate health care.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) report made 94 recommendations in the form of Calls to Action. Seven of these Calls to Action specifically relate to health.They explain the importance of engaging community members, leaders and others who hold important knowledge in the development of health care. As members of a team of Inuit and academic health care researchers, we have been working with health-system partners to support Inuit in cancer care. We focus on enhancing opportunities for Inuit to participate in decisions about their cancer care through the shared decision-making model, in a research project we call “Not Deciding Alone.”

We travel thousands of miles for cancer care

Our collective success in addressing the TRC Calls to Action will require health research to focus on addressing the health-care inequities experienced by Inuit, First Nations and Métis populations in ways that take action to promote self-determination.

This is important as current health-care models do not often support Indigenous values, ways of knowing and care practices.

[Read more: Indigenous knowledge is the solution to Canada’s health inequities]

Poor cultural awareness in our mainstream health care systems discourages Indigenous people from seeking care and engaging with health services. It increases the risk that Indigenous people will encounter racism when seeking care.

There are many documented instances of our health care system’s failure to provide appropriate health care to Indigenous people, due to unfair assumptions and demeaning and dehumanizing societal stereotypes.

These health system failures discourage people from seeking care, and have resulted in death, as in the case of Brian Sinclair, who died after a 34-hour wait in a Winnipeg hospital emergency room in September 2008.

There can also be significant physical barriers to care for Inuit. Critical health services such as oncology specialists and treatments are often located in urban centers such as Ottawa, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Montréal and St John’s, thousands of kilometers away from remote communities in Inuit Nunangat. This leaves many Inuit negotiating stressful urban environments, dealing with cultural dislocation and navigating complex health systems without the benefit of community support networks.

During our research, an Inuit peer support worker explained what it can be like for those who travel far from their family and community for their care: “People come with no idea of why, and we are having to bridge two worlds for them. Often patients have no idea why health-care providers tell them to get on a plane, and then they think they are coming for treatment for three days and then it becomes two weeks. It is a tough situation as often people have no money, no support. People need to be able to explain their situation and how it is for them. People need to know that they are not alone.”

Research shows that these geographical challenges significantly impact access to health care and are often exacerbated by language barriers. Together these factors may make people vulnerable to additional harms unrelated to the health conditions for which they seek treatment.

Patients and health care providers work together

Shared decision-making is an important evidence-informed strategy that holds the potential to promote patient participation in health decisions.

In this model, health-care providers and patients work together using evidence-based tools and approaches and arrive at decisions that are based on clinical data and patient preferences — to select diagnostic tests, treatments, management and psycho-social support packages.

Shared decision-making is considered a high standard of care within health systems internationally and it has been found to benefit people who experience disadvantage in health and social systems.

Shared decision-making has also been found to promote culturally safe care, and has the potential to foster greater engagement of Inuit with their health-care providers in decision-making.

The concept of cultural safety was developed to improve the effectiveness and acceptability of health care with Indigenous people. Culturally safe care identifies power imbalances in health-care settings — to uphold self-determination and decolonization in health-care settings for Indigenous people.

The aim of a shared decision-making approach is to engage the patient in decision-making in a respectful and inclusive way, and to build a health care relationship where patient and provider work together to make the best decision for the patient.

Most importantly, our approach has emphasized ways of partnering that align with the socio-cultural values of research partners and community member participants, both to develop tools and create approaches to foster shared decision-making. The term “shared decision-making” translates in Inuktitut to “Not Deciding Alone” and so that is the name of our project.

The results are outcomes that Inuit are more likely to identify as useful and relevant and that respect and promote Inuit ways, within mainstream health-care systems.

Self-determination through Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Our research uses the guiding principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit — a belief system that seeks to serve the common good through collaborative decision-making — as the foundation for a strengths-based approach to promote Inuit self-determination and self-reliance.

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit principles have been passed down from one generation to the next and are firmly grounded in the act of caring for and respecting others.

There is important learning taking place within academic and health-care systems that involves deepening understandings of what “patient-oriented care” means. We need to learn how to do research in partnership with those who are the ultimate knowledge users in cancer-care systems — patients.

In our work, Inuit partners and community members are leading the development of shared decision-making tools and approaches, building on their strengths and resiliency. Our research and health systems are beneficiaries of these partnerships that hold potential to create health care that is welcoming and inclusive for all.

With guidance and support from Inuit and more broadly, from Indigenous partners, we are learning how to take action on the TRC recommendations, and to make respect and kindness integral to best practice in research and health care.

Janet Jull is assistant professor at the School of Rehabilitation Therapy at Queen’s University, Ontario and works with Inuit Medical Interpreter Team of Ottawa Health Services Network Inc.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.