Arctic countries have begun working together to step up nuclear accident preparedness

International collaboration to prevent and respond to nuclear accidents has begun, but an Arctic Council agreement would help strengthen such work.

Øyvind Aas-Hansen with the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority (DSA) is happy to cooperate with Aleksandr Vazhenin and Pavel Borisov from the Emergency Response Centre of Rosatom, Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation.

A sharp increase in nuclear-powered vessels in Arctic waters is cause for concern among international safety experts who recently teamed up on a voyage to the Bear Island and Svalbard to see how drones can be used to detect possible hazardous radiation.

“Drones could be a very sufficient tool for emergency response units in case of nuclear accidents at sea,” saysAas-Hansen, a senior advisor with DSA. Safety for rescue workers is always a priority and real-time knowledge about radiation levels is essential during all risky operations.

Worst case scenario is reactor meltdown in a nuclear-powered vessel or fire in a cargo ship carrying radioactive waste where crew members have to abandon the ship.

Northern Norway saw a record number of 12 visiting NATO nuclear-powered submarines in 2018. Surfacing near Hekkingen fyr in Malangen west of Tromsø, the subs are in for supplies or crew change before continuing the cat-and-mouse hunt for Russian submarines sailing out in the strategically important waters between Norway, Iceland and Greenland.

It was here, in international waters outside Senja in Troms, the Russian Echo-II class submarine K-192 suffered a severe reactor coolant accident 30 years ago, on June 26th 1989. Radioactive iodine was leaking with the reactor-steam while the vessel was towed around the coast of northernmost Norway to the navy homeport at the Kola Peninsula.

Fearing similar accidents could happen again, Norway is pushing for international awareness to help advance radiation emergency preparedness.

A dedicated task force group was recently established under the Arctic Council aimed at sharing knowledge and experiences between national radiation authorities and other rescue services.

Arctic radiation agreement

“Norway has suggested to form an expert group to work out an Arctic Council agreement for radiation emergencies, like already exists for oil spill and search-and-rescue cooperation,” says Aas-Hansen.

He says such an agreement will not replace any well-working arrangements like the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) Convention of Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident, but rather complement it with strengthened cross-border maritime preparedness for the Arctic.

“IAEA has no objections. An Arctic Council radiation expert group and agreement is needed. We are worried about the sharp increase in nuclear-powered vessels sailing north,” Aas-Hansen explains. “The Council is consensus based, so if none of the member countries protest, the expert group will be operating from after the upcoming December meeting in Reykjavik.”

Iceland holds the Chair of the Arctic Council for the period 2019 to 2021.

An Arctic cooperation agreement on the handling of maritime radiological and nuclear emergencies will open the door for multinational exercises, better exchange of information and plans for coordinated response when the nuclear alarm bell rings.

Meanwhile, international experts on radiation monitoring teamed up with industry developers looking at the potential for using unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in the Arctic. The Barents Observer was on board when about 30 stakeholders from Russia, United States, Germany, Switzerland and Norway this June sailed from Tromsø via Bear Island to Svalbard for the Arctic Drone Event where the 2019 focus was explicitly radiation preparedness and response.

The drone event was initiated by NITO — The Norwegian Society of Engineers and Technologists, and was organized as a voyage on board “Helmer Hanssen”, a research ship belonging to UiT-The Arctic University of Norway.

“As an organization with nearly 90,000 members, we are concerned with more than just salary and tariffs,” says President of NITO Trond Markussen, who participated on the voyage. “Technological expertise is a prerequisite for solving the challenges we face. Not least in the vulnerable north. If we can contribute to connect environmental and safety agencies with the technology communities, we have achieved the goal with these drone events gatherings.”

Flying geiger counter

Some environments are too risky for humans to survey and collect data. A nuclear accident site could be one such spot, especially if it happens at sea.

UAVs, better known as drones, could carry a geiger counter, camera or other tools in the air over hazardous objects like a submarine on fire. From safe distance, emergency response units could then be better prepared before boarding or sailing close-up.

In both the United States and Russia, nuclear emergency teams are already equipped with a wide range of drones, either it is fixed wing or quadcopters. The technology, though, is still in an early phase of development.

Aleksandr Vazhenin, head of Rosatom’s Radiometric Department in St. Petersburg, explains the importance of cross-border cooperation.

“We get exchange of information on measurement equipment and laboratory procedures. It increases the level of mutual trust.”

Rosatom’s emergency team, however, is only responsible for civilian nuclear objects like power plants and the Murmansk-based fleet of icebreakers.

“It is difficult,” Vazhenin says when asked about possible cooperation with the navy who operates the nuclear-powered submarines.

Also present on the voyage to Svalbard was representatives from Nevada National Security Site (NNSS) remote sensing lab in the United States. Like Rosatom, NNSS operate drones and detecting aerial systems that could be deployed anywhere possible releases of radioactivity might happen.

In the Arctic Council work, both U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) and Rosatom are partners. So is the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority, Danish Emergency Management Agency and Norway’s DSA.

More reactors at sea

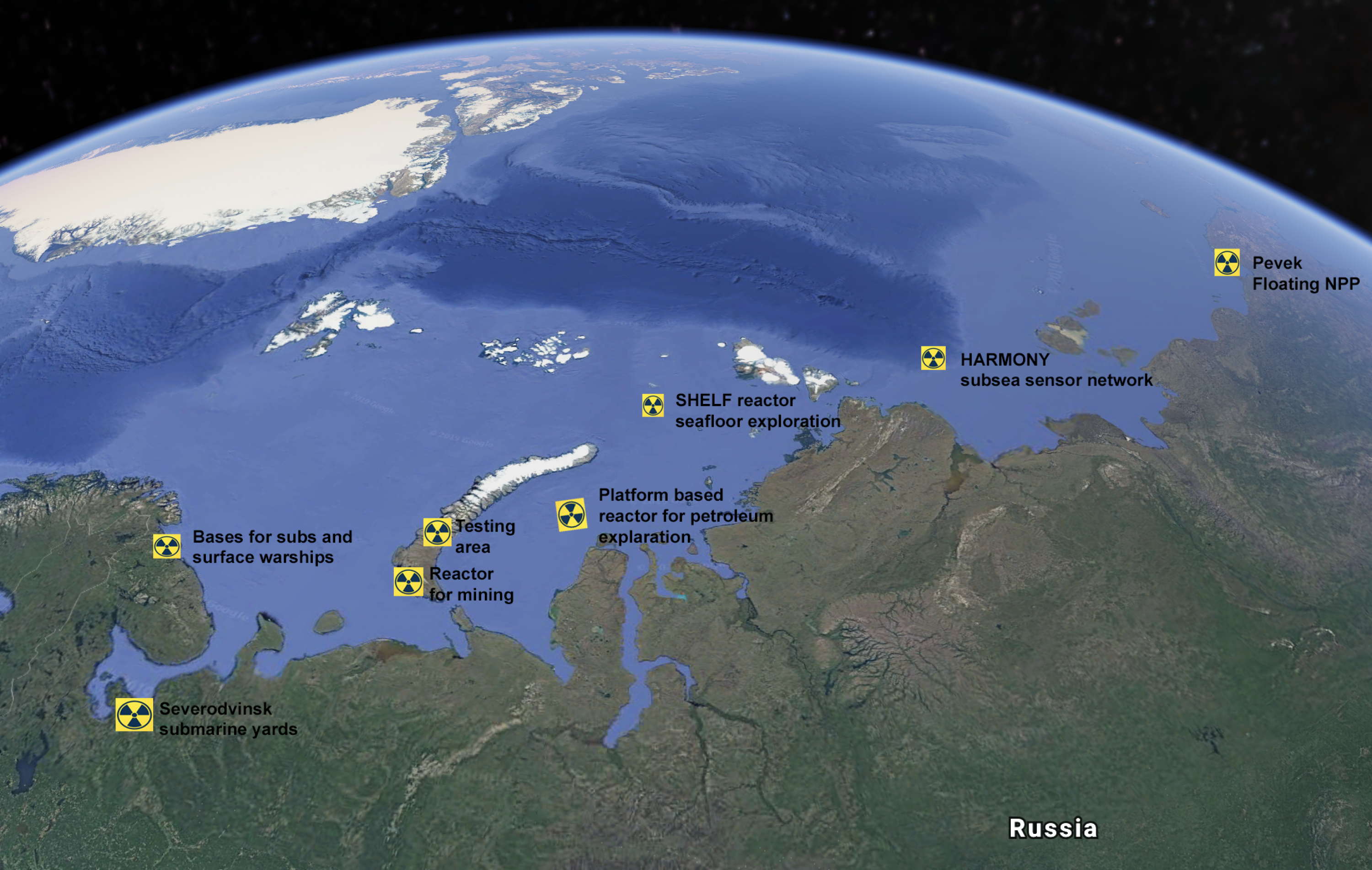

The Barents Observer has recently published an overview listing the increasing number of reactors in the Russian Arctic. The paper is part of Barents Observer’s analytical popular science studies on developments in the Euro-Arctic Region.

According to the list there are 39 nuclear-powered vessels or installations in the Russian Arctic today with a total of 62 reactors. This includes 31 submarines, one surface warship, five icebreakers, two onshore and one floating nuclear power plants.

Looking 15 years ahead, the number of ships, including submarines, and installations powered by reactors is estimated to increase to 74 with a total of 94 reactors, maybe as many as 114. Additional to new icebreakers and submarines already under construction, Russia is brushing dust off older Soviet ideas of utilizing nuclear power for different kinds of Arctic shelf industrial developments, like oil and gas exploration, mining and research. “By 2035, the Russian Arctic will be the most nuclearized waters on the planet,” the paper reads.

And existing icebreakers and submarines will see their service life prolonged. The average age of the Northern Fleet’s nuclear-powered submarines has never been older than today. Several of the submarines built in the 1980s will continue to sail the Barents Sea and under the Arctic ice-cap until the late 2020s.

In August, Russia’s first floating nuclear power plant, “Akademik Lomonosov,” will be towed from Murmansk to Pevek, a port town on the northeast coast of Siberia.

Other plans to use nuclear reactors in the Russian Arctic in the years to come include many first-of-a-kind technologies like sea-floor power reactors for gas exploration, civilian submarines for seismic surveys and cargo transportation, small-power reactors on ice-strengthen platforms.

In the military sphere, the Arctic could be used as testing sites for both Russia’s new nuclear-powered cruise-missile and nuclear-powered underwater weapons drone. Both weapons were displayed by President Vladimir Putin when he bragged about new nuclear weapons systems in his annual speech to the Federation Council last year.

An Arctic Council summary report printed this spring by the Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response Working Group highlight the risks: “The presence of radiological and nuclear material in the Arctic poses a risk for serious incidents or accidents that may affect Arctic inhabitants and their communities, the Arctic environment, and Arctic industries, including traditional livelihoods such as fisheries and local food sources.”

For Norway and Russia, a nuclear accident in the Barents Sea could be disastrous for sales of seafood. The two countries export of cod and other species is worth billions of Euros annually.

In Norway, the Coast Guard and Sysselmannen, the Governor of Svalbard, are using drones for different purposes.

Drone pilot Bård Alexander Raunlid says the Coast Guard aims at having drones on board all vessels within some few years. “The mission is for information collecting and sharing to achieve situation awareness between joint agencies.”

Raunlid explains how drones can be used for fisheries inspections, search-and-rescue, oil pollution and different police tasks. “We are soon to enter a cooperation with the Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority.”

The Norwegian Coast Guard’s area of responsibility is from Sagerak and the North Sea in the south to the Norwegian and Barents seas in the north, including the waters around Svalbard. With deliveries from 2022 to 2024 Norway gets three new ice-classed vessels, the largest Coast Guard ships to sail the European Arctic.

But drones have limitations, not least in the Arctic.

Most drones can’t fly for more than 30-40 minutes without their batteries running low. The colder it is, the shorter time in the air. Wind and polar darkness are other challenges. Icing on wings and propellers could crash a drone within seconds. And the further north you are, the more misleading are the GPS signals used for navigating the drone.

For Arctic purposes, Svalbard is a perfect place to test drone technologies.