How Arctic governance could become a testing ground for Sino-US relations

The Arctic is becoming an important testing ground for US-China relations. As the world tries to work out ways to deal with how climate change is altering the region, the Arctic has the potential to provide an example of how the two global powers can cultivate peaceful co-existence.

Both countries have an interest in the Arctic – but for very different reasons. The United States, through Alaska, is one of five coastal states of the Arctic Ocean and plays a stewardship role in the region. China is the world’s largest producer for marine capture fisheries and the world’s third-largest shipowner – two strong economic interests in the resources-rich Arctic region.

[Chinese president makes surprise visit to Alaska after Trump summit]

The Arctic Five – the US, Russia, Canada, Norway and Denmark through Greenland – believe that since an extensive international legal framework already applies to the Arctic Ocean, there’s no need for another.

But Arctic ice is melting at an alarming rate, enabling increased human access to formerly ice-covered areas. And this has increased the potential for intensifying fishing, shipping, tourism, bioprospecting and mining in the region.

Clearly, these changes present significant challenges that the Arctic governance regime needs to evolve to meet.

Simmering tension

In recent years, China’s economic success has bolstered Beijing’s confidence in asserting its position in regional and global affairs. Chinese diplomacy has become more active.

The country has, for instance, been advancing the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, which intends to construct a Silk Road Economic Belt and Maritime Silk Road to connect Asia, Europe and Africa. And it has been making remarkable progress.

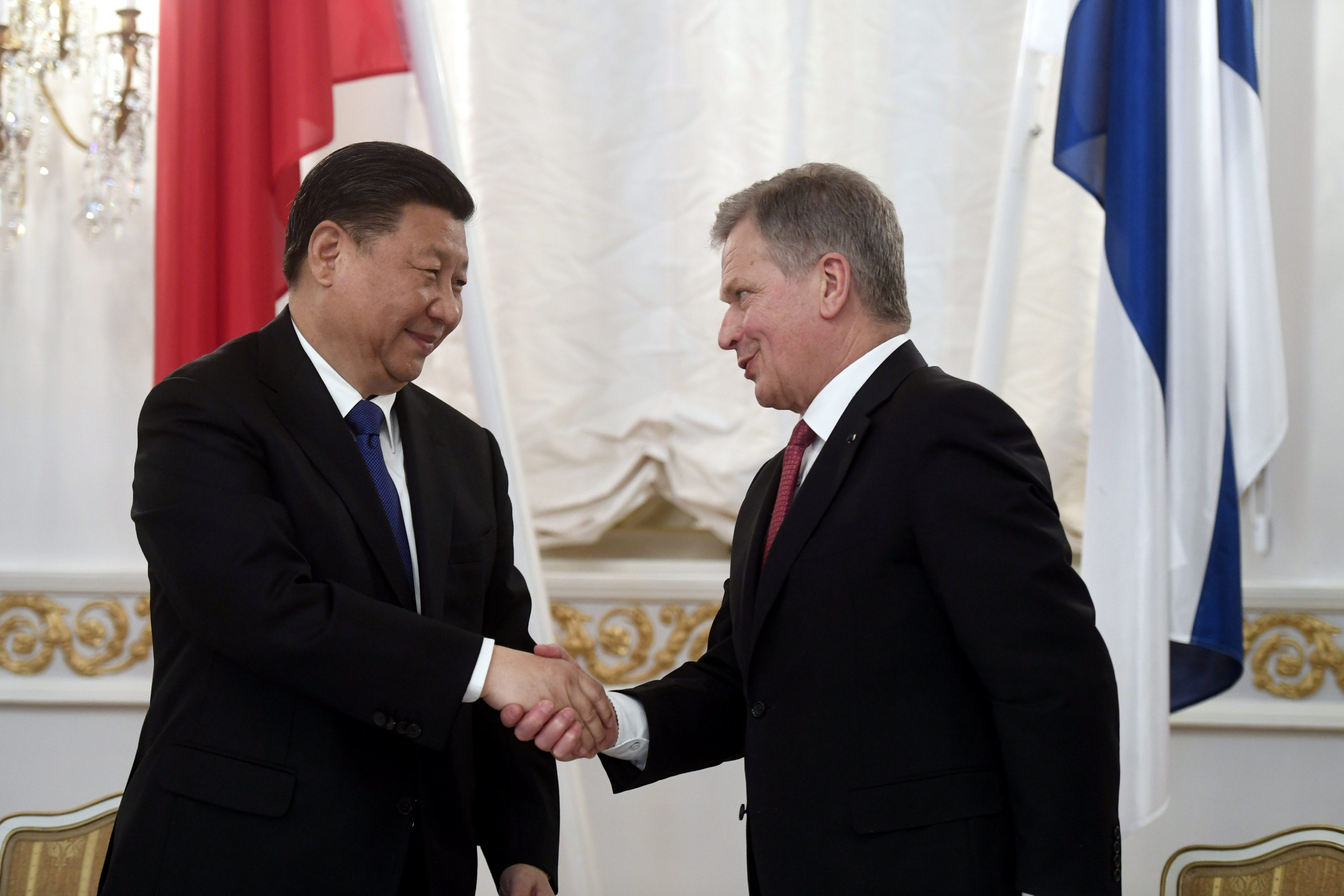

[Xi says China, Finland to increase cooperation under China-EU framework]

Achievements in 2016 alone include the opening of Gwadar Port in Pakistan, run by China Oversea Port Management Corporation, as well as the Djibouti Navy Base – China’s first navy support base on foreign soil.

Under the Obama administration, the United States advanced the Asia-Pacific Rebalance Strategy in an attempt to contain China’s growing influence in the region. And Donald Trump’s presidency could pose a new challenge to the Sino-American relationship, not least due to Trump accusing China during his campaign of “raping” the US because of “unfair trade policies”.

At the same time, China has been condemning the US for being the root of tensions in the South China Sea. The planned deployment of the THAAD anti-missile system in South Korea has also deeply angered China.

It is not surprising, then, that there are concerns relations between the two nuclear-armed countries could deteriorate into an economic or military confrontation in the Trump era.

Chinese interests

Since changes in global governance result from bargaining between rising powers and incumbents, the Arctic could come to act as a barometer for US-China relations. Evolving Arctic governance could provide the ideal testing ground for how the two countries can work together.

China is expected to publish its first official Arctic policy soon. According to Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs Zhang Ming’s speech at the third Arctic Circle Assembly in 2015, China now clearly identifies itself as a “near-Arctic state” and a major stakeholder in the region.

[Chinese leader Xi’s Finland stopover on way to Trump reveals global trade shift]

Ming said the Chinese government believed that the changing environment and resources of the Arctic have a direct impact on China’s climate, environment, agriculture, shipping and trade as well as social and economic development. At the same time, China has the political will to contribute to shaping Arctic governance.

While China has thus far emphasised a cooperative attitude in Arctic affairs, it might become more assertive in the governance of the region in response to confrontation with US in other parts of the world. It could, for instance, use the Arctic as a trade-off for a US compromise in South China Sea disputes.

US leadership

For the US, the Arctic could present a litmus test of the strength of its leadership in global affairs. To date, the US has been a leader on many global issues and the Arctic is no exception.

Negotiations on the regulation of high sea fisheries in the central Arctic Ocean, for instance, is a US-led process. These were initiated in 2007 by a joint resolution of the US Senate, which called for a moratorium on Arctic fisheries until an adequate instrument was adopted.

In 2015, the Arctic Five adopted the Oslo Declaration and invited China, the European Union, Iceland, Japan and South Korea to join the process for developing a regional fisheries organisation or arrangement for the central Arctic Ocean.

Under US leadership, the so-called Arctic 5+5 negotiations have made important progress. Held from March 15-18 2017, the grouping’s latest meeting in Reykjavik, Iceland, issued a statement emphasising that consensus had been reached on most issues and that there was a general commitment to conclude the negotiations soon.

China, though a major global player in distant water fishing, did not challenge US leadership in these negotiations.

A potential template

Sino-US relations in the Arctic will also provide insights into the effectiveness of American diplomacy in the Trump era. The Obama administration achieved considerable success on this front.

It incorporated central Arctic fisheries into the eighth US-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue Special Joint Conference on Climate Change, for instance. And the US initiative on fisheries regulation in the central Arctic Ocean was reaffirmed in a bilateral meeting between Barack Obama and Xi Jinping during the G20 Summit in Hangzhou in September 2016.

Indeed, the success of the Obama administration in Sino-Arctic diplomacy could explain why the Chinese government supports the ongoing Arctic 5+5 negotiations. Whether the Trump administration can continue to effectively engage the Chinese on Arctic governance issues remains to be seen.

Future Arctic governance could not only be impacted by broader US-China relations, it could also provide a template for how the two global powers can work together.

Nengye Liu is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Adelaide and Michelle Lim is a Lecturer in environmental and sustainability law at the University of Adelaide

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.