How Canada’s northernmost community is handling Nunavut’s new COVID-19 lockdown

“Everybody here is taking it seriously.”

In Grise Fiord, about 1,500 kilometers north of the nearest COVID-19 infection, the 150 or so residents in town are living under the same two-week lockdown as everyone else in Nunavut.

Grise Fiord, or Aujuittuq — ”the place that never thaws” — in Inuktitut, is the most northerly community in the territory, and in Canada. Located on Ellesmere Island, at 76 degrees 25 minutes North, it’s a place where the sun sets at Halloween and won’t rise again until Feb. 10 next year.

In Grise Fiord there may be no COVID-19, but “everybody here is taking it seriously,” Anne Akeeagok told Nunatsiaq News on Wednesday, Nov. 18, the first day of the lockdown that will continue to Dec. 2.

The lockdown is intended, as Nunavut Premier Joe Savikataaq said, to be a “circuit-breaker,” to stop the growing number of new coronavirus cases in the territory.

[Nunavut COVID-19 lockdown begins as cases continue to rise]

Imposed after cases jumped this month from none to 70 by Nov. 18, it comes with a number of restrictions to keep people safely at home.

In close-knit Grise Fiord, where visiting is a natural part of life, there’s no visiting now “unless you have to go out and see somebody,” Akeeagok said.

Many of Akeeagok’s closest family members live too far away to visit: her parents, Margaret and Mike Gardiner, a retired Anglican minister and winner of the Order of Nunavut, are in a long-term care home, the Embassy West Senior Living residence in Ottawa, about 3,500 km away.

She hasn’t seen them since September 2019.

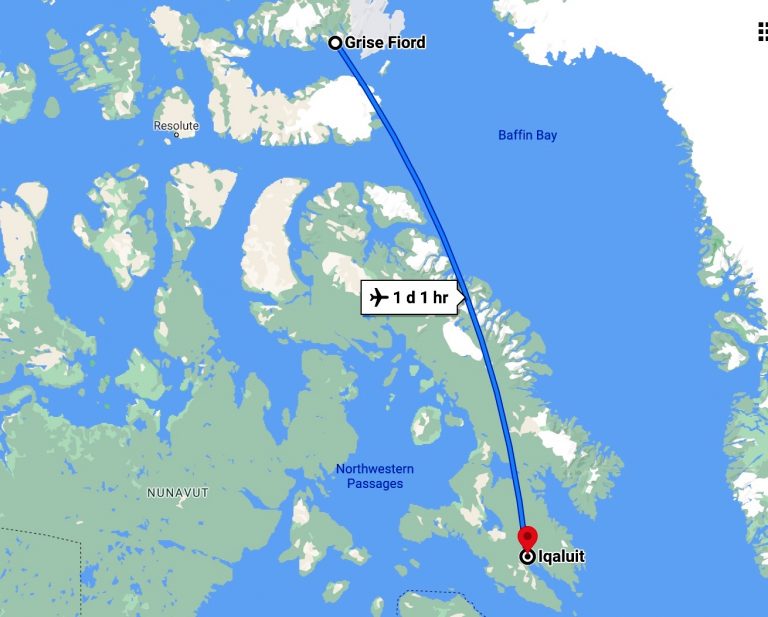

Her sisters, Susan Black and Pat Angnakak, an Iqaluit MLA, live in the territorial capital, about 1,500 kilometers to the south, as does Akeeagok’s son P.J. Akeeagok, who is president of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, and his family.

Also in Iqaluit is the closest hospital, the Qikiqtani General Hospital.

But to get there requires a journey of several hours, at best, in an air ambulance or up to 25 hours on a commercial flight.

As nurses look after the community’s health needs, everyone is doing their best to comply with the new measures to keep COVID-19 away, Akeeagok said.

“I know our government is looking after us,” she said. “We hope it doesn’t come here.

“We are a small community. We all are worried and hoping it doesn’t come here.”

Since the lockdown started, Akeeagok, a Government of Nunavut employee, is working from home like everyone else.

It’s hard for the community’s young kids not to see their grandparents, aunts or uncles, she said.

“But the kids here are very good once they are told something,” she said.

The 30 or so children at Umimmak school are now studying at home for the next two weeks, using learning packages prepared by their teachers.

Regular updates on COVID-19 come from Grise Fiord’s mayor, Meeka Kiguktak, who is also the local Health Department representative, and Nunavut’s chief public health officer, Dr. Michael Patterson.

“We all have to follow what the government and Dr. Pat says. We’re not used to it but we have to try our best, everyone has to try their best, and also to help each other,” Akeeagok said.

That is the larger-than-life power of Grise Fiord, whose first residents were dropped off on Ellesmere Island by Canadian federal government agents in the early 1950s to serve as “human flagpoles” for Canadian sovereignty: they earned an official apology from Canada only in 2010.

As Larry Audlaluk, one of the Arctic relocatees and author of a new book, “What I Remember, What I know: The Life of a High Arctic Exile,” put it during a recent conversation with Nunatsiaq News, “We survived. We lived. Most of us, we survived up here. There is always hope and light at the end of the tunnel.”

It’s never been easy to live in the dark and cold for most of the year.

“I know that in times of crisis they band together to help each other,” said Nunavut’s deputy premier, David Akeeagok, about people in Grise Fiord.

He is from Grise Fiord and represents the community in the territorial legislature as MLA for the High Arctic riding of Quttiktuq.

“I know being isolated is very difficult, but we have to do this for the sake of our health,” he said.

He takes some comfort because Grise Fiord is so isolated, “more than any other communities in Nunavut.”

And the Nunavut government is standing by and would be ready to send its COVID-19 rapid response team in, if necessary, he said.

For now, business at the local Arctic Co-operatives Ltd. store, the only store and business now open in Grise Fiord, continues as usual, in the “new normal” way, said manager Mike Mandla Sibanda.

“We are taking it as we have COVID,” he said. “Safety first. We’re not taking any chances, we are doing our very best to get ready for it.”

Customers now wear masks, and they receive a free disposable mask if they don’t have one. There’s a hand-sanitizing station and Plexiglas to protect those at the cash register and at the post office counter.

Elders check out at the cashier first if they are ready to go, and children under 14 must be accompanied by an adult.

The co-op, with five employees, has now hired an extra person to help clean.

The store is regularly stocked, Sibanda said.

Everything comes in via Resolute Bay, an hour and a half away by air.

“We’re still getting our orders on time, but we have increased our orders. If anything happens, we have a big warehouse,” he said.

The pandemic has brought some financial assistance to Grise Fiord to help residents with the high cost of food, which can be as much as a third or more higher than elsewhere in Nunavut.

Pandemic subsidies from the federal government’s Indigenous Community Support Fund and the Qikiqtani Inuit Association recently brought in $1,000 per family—an expansion of a $2-million emergency initiative that the QIA rolled out last April at the height of the pandemic’s first wave.

The money is to help with harvesting country food, buying groceries and cleaning products, and buying sewing supplies to make warm winter clothes.

There are challenges in Grise Fiord beyond COVID-19: the board of the local hunters and trappers association agreed recently that the three polar bears hanging around town were not scared of the bear bangers and vehicles anymore, were “getting braver every day,” and would have to be put down for the community’s safety.