How Canada’s UN submission will (eventually) draw some of the last lines on its map

But it will be years before the process is complete.

In May 2019, Canada made a partial submission to the United Nations to recognize an extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles in the Arctic Ocean. This means that Canada will soon have the last lines drawn on the map of Canada.

Canada’s submission was made to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) under Article 76 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

There was surprisingly little fanfare over this extraordinary accomplishment in a week of maritime-related accomplishments that included Canada acceding to an international moratorium to prevent unregulated commercial fishing in the central Arctic Ocean.

As a political scientist, I want to understand the processes used, the states involved and the international organizations and law that guided this extraordinary example of global governance.

Shelf’s edge

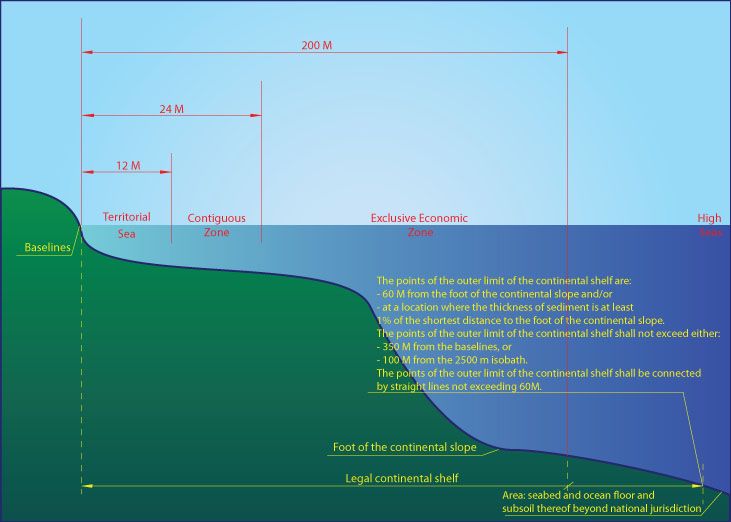

First, what is the continental shelf? Imagine you are standing on an ocean beach. You decide to keep walking for as long as you can feel ground beneath your feet. This ground is the seabed and subsoil, and coastal states have inherent right to explore and exploit the natural resources.

According to UNCLOS, this does not depend upon occupation or an express proclamation; in other words, Canada need not provide any justification. And if the coastal state can provide evidence that its continental shelf extends beyond 200 nautical miles — the outer continental shelf — Canada can explore and extract mineral and other non-living resources from the seabed and subsoil.

Canada’s partial submission to the CLCS, which includes written explanations and physical evidence, was led by branches of the federal government: Global Affairs Canada, Geological Survey of Canada and the Canadian Hydrographic Service.

There was also extensive assistance and participation by various Indigenous groups, Canada’s territorial governments, Parks Canada, the Canadian Ice Service, the Canadian Coast Guard, Defence Research and Development Canada and the Department of National Defence.

Collecting information

Collecting data in the Arctic is extremely difficult and costly. It is only possible to navigate the Arctic in the summer months, and even then, the perennial ice coverage and weather, wind and current conditions pose challenges.

Data collected for Canada’s submission included bathymetric, gravimetric, seismic, aero-gravity and aerometric information. Retrieving 800 kilograms of rock samples and three piston cores involves engineering and scientific feats of marvel, bravery and sheer determination.

Considering Canada had more rock samples from the moon than from the Arctic, it is a reminder of how little is known about the Arctic. Imagine, therefore, the scientific breakthroughs Canada and the world have yet to discover with this data especially now that government scientists helping with Canada’s submission are now at liberty to publish their findings in academic journals.

Collaboration and geopolitics

Canada’s submission was aided by collaboration with the governments of Denmark, Sweden (and especially its icebreaker Oden), the U.S. and Germany.

The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by five coastal states: Canada, Russia, the U.S., Denmark (via Greenland) and Norway. It was anticipated by all of the Arctic states that Russia, the U.S., Canada and Denmark, by virtue of their adjacent and opposite locations, could have overlapping claims.

It was expected that all four would collect data from at least some of the same areas of extended continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. Russia, Denmark and Canada have all made at least partial submissions to the CLCS which will review the scientific evidence and provide technical feedback regarding the scientific integrity of the data provided.

The CLCS cannot reconcile overlapping claims. Annex 1 of the CLSC’s rules of procedure notes that “matters regarding disputes which may arise in connection with the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf rests with States.”

Establishing boundaries

Canada, Russia, Denmark and the U.S. are expected to continue to negotiate, as they will have the final say in determining the extent of the boundaries. This means Canada has years to wait before the process is completed, and there are a few caveats to keep in mind.

First, given the highly technical nature of the evidence and the few number of commission members, Canada’s submission is not expected to be fully reviewed by the CLCS for many years. Canada’s Arctic submission is currently number 84 on the CLCS’ list.

Second, the U.S. is not a party to UNCLOS although it does treat much of it, including Article 76, as customary law (meaning the U.S. agrees to the outlined principles). The U.S. has an active Extended Continental Shelf program and the government is collecting data in anticipation of ongoing negotiations.

Third, there is no time crunch for the resources of the extended continental shelf given the distance, cost and difficulties to access them. Many tend to assume that resources do exist for exploitation, but it could also be that there is nothing of commercial worth available.

Fourth, any resources and activity within the water and airspace beyond 200 nautical miles from the coastal baseline belongs to everyone and is governed by international law.

Finally, there are limitations in UNCLOS on the extent of the continental shelf and Article 82 of UNCLOS provides for a system of revenue sharing by means of payments or contributions in kind with respect to the extraction of non-living resources of the continental shelf lying beyond 200 nautical miles. Given the small size of the Arctic Ocean, however, most of it is already captured within the Arctic coastal states’ exclusive economic zones.

Canada’s Executive Summary submission is available for anyone to review. Despite the complexity of the data, the submission is very readable and excellent scholarship. This reflects the extraordinary work of Canada’s scientists and civil servants, and is an example of global governance working well.

Andrea Charron is associate professor and director of the Centre for Defence and Security Studies at the University of Manitoba.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.