How Iceberg Alley got its name — and why it may be under threat

Warmer years tend to see fewer icebergs reach Labrador and Newfoundland.

Iceberg Alley, the stretch of coast ranging from Labrador to Newfoundland in Canada, is the southernmost region of the northern hemisphere where one can regularly see icebergs. But hurry up! As the planet continues to warm, Iceberg Alley may soon lose its name.

Iceberg sightseeing is a common — and much-anticipated — activity in Newfoundland. Every spring, locals and visitors brave the region’s damp and chilly weather — it’s one of the foggiest places on the planet — to scrutinize the horizon for large white objects or embark on boat tours, hoping that luck will be on their side.

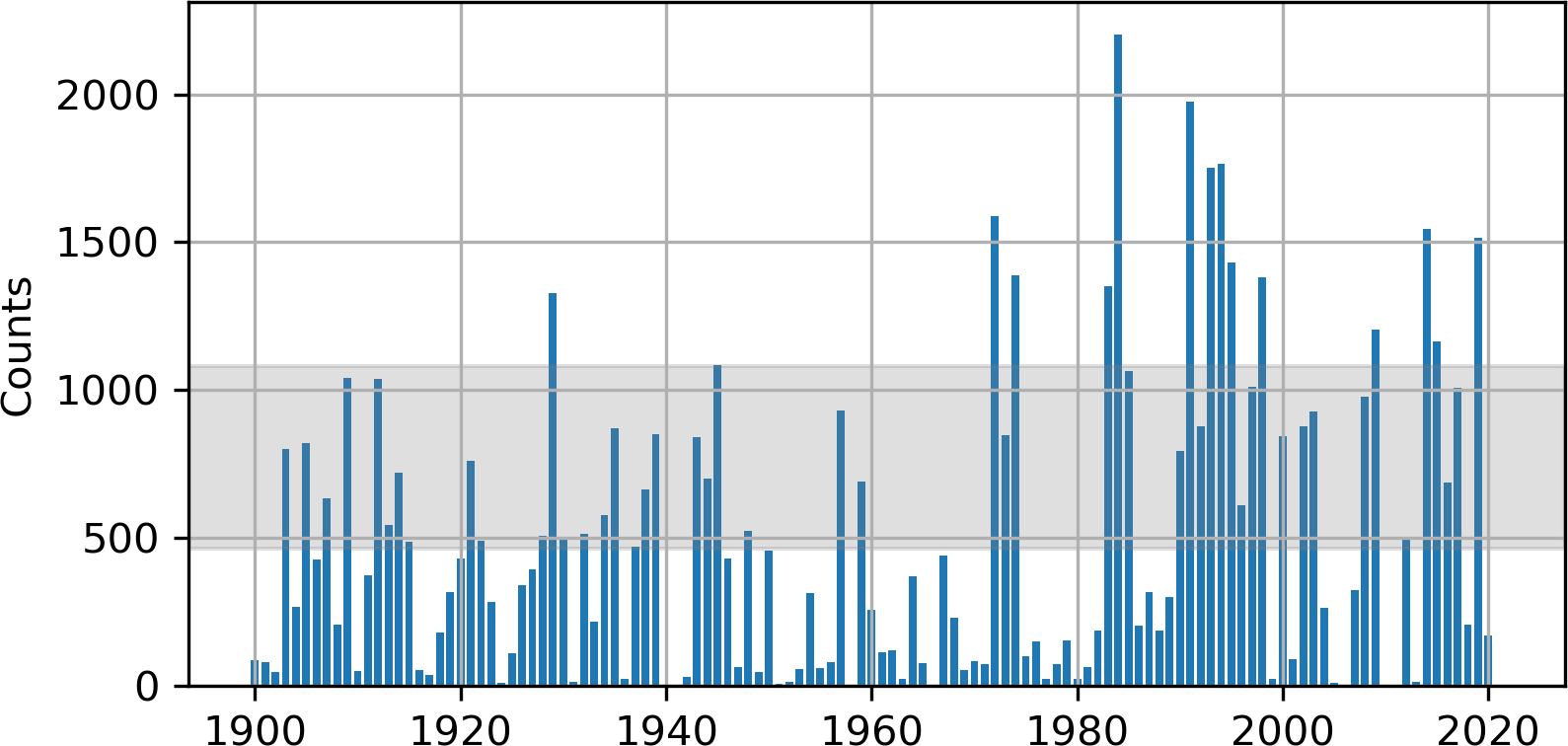

But with iceberg counts ranging from zero to more than 2,000 per year, booking a trip in advance to see these 10,000-year-old blocks of ice can be a gamble.

10,000-year-old ice

Every year, hundreds of billions of tonnes of ice, equivalent to more than 100 million Olympic pools of water, once melted, is shed from Greenland’s glaciers into the ocean. This phenomenon is called calving.

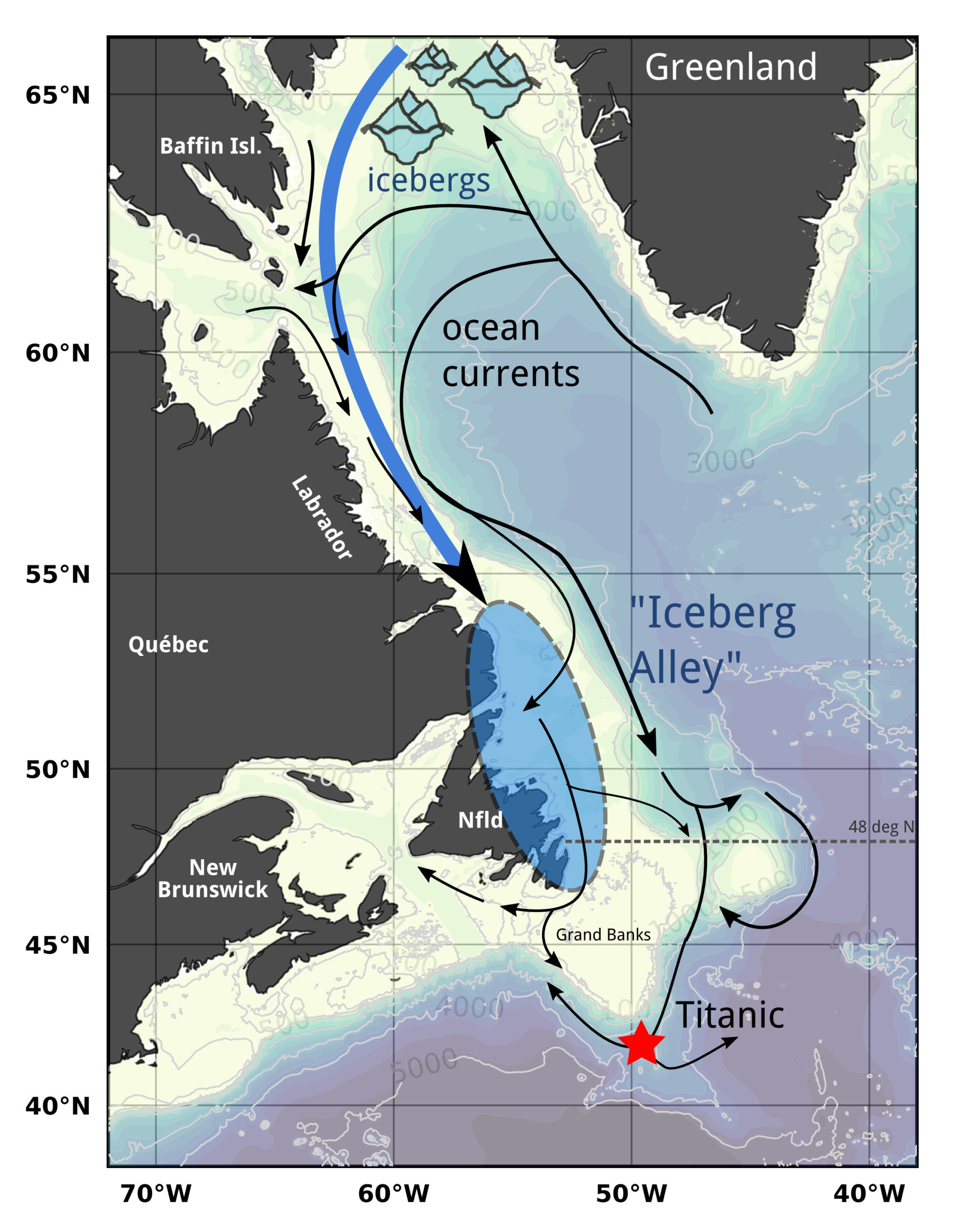

The bulk of the ice calving from Greenland’s glaciers form icebergs. While about 10-50 percent of these icebergs melt directly in Greenland’s fjords, the majority are carried away by ocean currents.

The Greenland ice sheet is the result of thousands of years of snow accumulation that has reached a thickness of more than one kilometer. The pressure that comes from the enormous weight transforms the snow into ice. The same pressure pushes the glaciers — rivers of ice funneled by numerous fjords — towards the ocean where they calve and form icebergs.

A subset of these icebergs, mostly originating from the west coast of Greenland, will reach Newfoundland. While these icebergs can live for as long as a decade, those reaching Newfoundland are generally one to two years old.

Sinking of the Titanic

The most famous of these icebergs is probably the one that sank the Titanic just south of the tip of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in 1912. That year was not an abnormal one for icebergs, with 1,038 icebergs reported. Following this tragedy, in 1913, the International Ice Patrol, operated by the U.S. Coast Guard on behalf of several maritime nations, was created to monitor iceberg dangers for ships in the North Atlantic.

The International Ice Patrol’s annual count of the number of icebergs that slip south of 48 degrees north provides the longest and most reliable time series of icebergs in Newfoundland. In an average year, nearly 800 icebergs are expected to cross the boundary, which lies just north of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

(Frédéric Cyr, Author provided)

These annual counts are extremely variable and affected by the climate of the North Atlantic. The 1980s and ‘90s were an especially cold period in the region, and more than 1,500 icebergs were observed during some of those years, with a record high of 2,202 in 1984. More recently, 1,515 icebergs were spotted in 2019, a year characterized with colder than normal spring temperatures and immediately following another cold period in the mid-2010s.

But these numbers decrease drastically during years characterized by milder winters and an early spring. This occurred in 2010 and 2021, where only one iceberg was observed; in 2011, which saw two icebergs; and in 2013, where 13 icebergs were recorded. Only two years, 1966 and 2006, in the 122-year time series have reported no icebergs journeying south of 48 degrees north.

An uncertain future

With the planet warming up as a result of anthropogenic climate change, the Greenland ice sheet is losing mass. While this may suggest that more icebergs will calve into the ocean, it is far from guaranteed that this will lead to more sightseeing opportunities in Newfoundland. And the numbers may lie, as improvements in iceberg-detecting technology may be responsible for an apparent upward trend in counts.

The environmental parameters that control the number of icebergs in Newfoundland in a given year remain unclear. However, it appears that a warmer climate definitely leads to fewer or simply no icebergs at all in Newfoundland.

For example, when looking at the region’s three warmest years on record — 1966, 2010 and 2021 — only zero, one and one icebergs were reported. These outliers may well become the new norm as climate projections suggest with a high level of confidence that the frequency and severity of extreme events, such as an anomalously warm year, will increase in the future.

While the Newfoundland iceberg sightseeing tourism industry may well have benefited from a succession of exceptional iceberg seasons linked to a recent rebound in cold ocean conditions in the mid-2010s, its future is less certain.

Will the Iceberg Alley lose its name? It would be unfortunate, but it is possible. For the moment there is still time to enjoy these 10,000-year-old remnants of the past. So hurry up before it’s too late!

Frédéric Cyr is an adjunct professor of physical oceanography at Memorial University of Newfoundland.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.