How remote Arctic communities can tap into river power

Northern communities like Igiugig, Alaska, are increasingly looking to renewable energy instead of diesel to power microgrids.

Arctic renewable energy has the potential for a global impact, but stories of energy transformation in the region are often overshadowed. For the month of September, ArcticToday is launching a special focus on renewable energy in the Arctic and this piece is part of that coverage. Find the full series here, or subscribe to our daily newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter to be the first to read new installments.

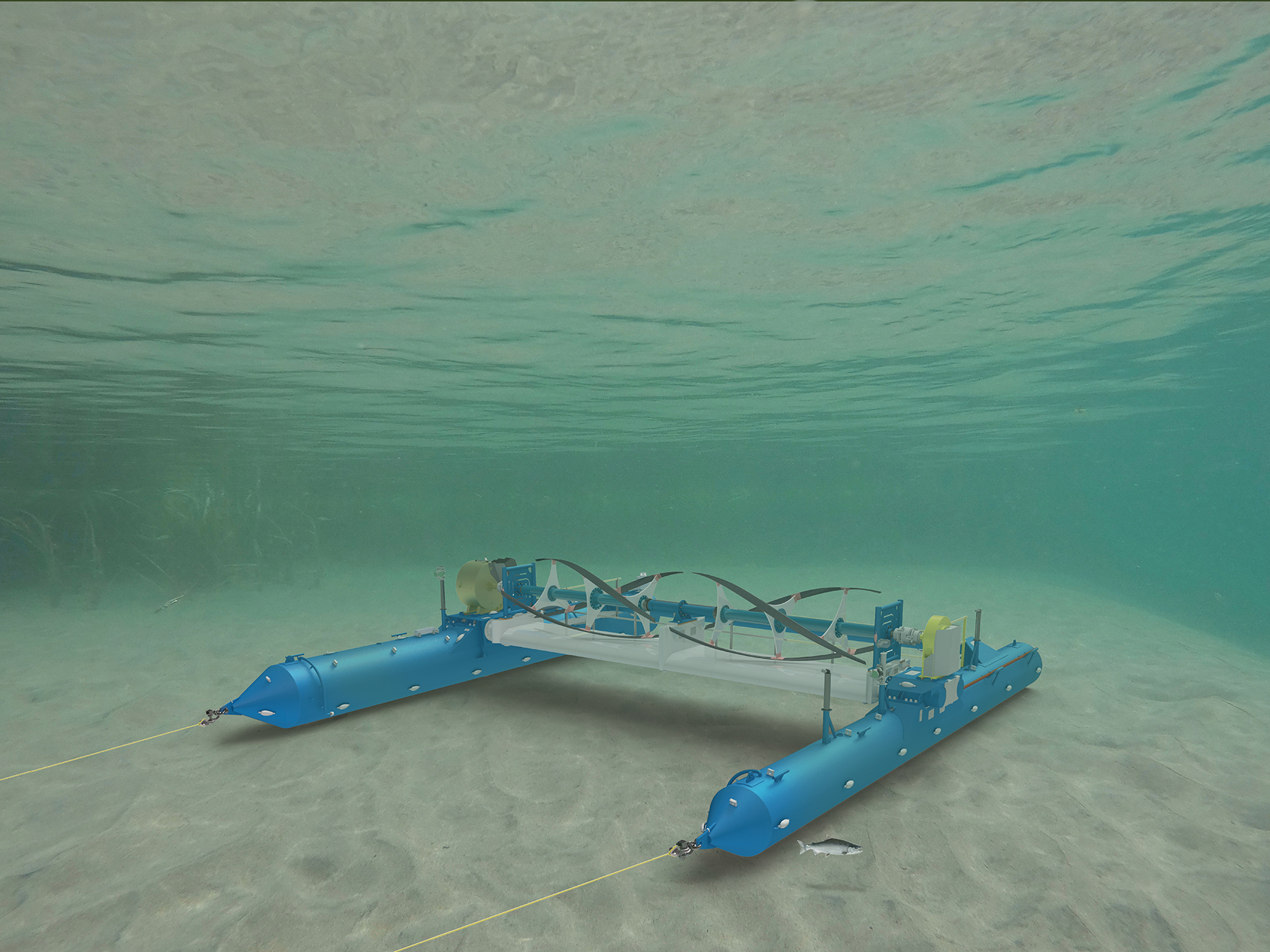

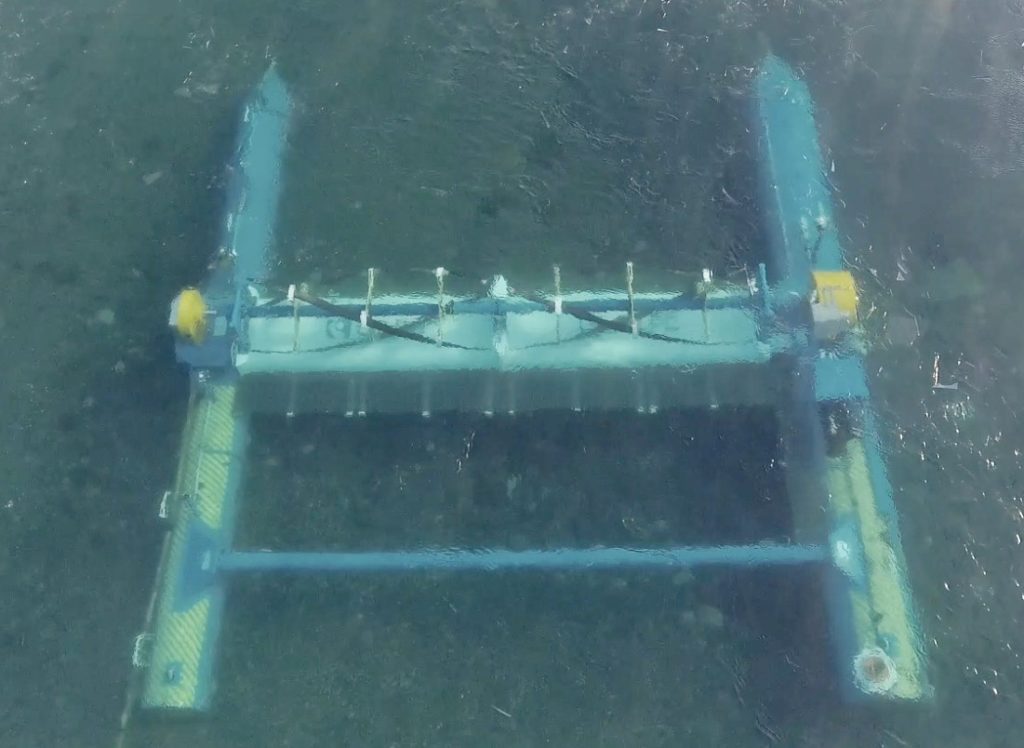

The river ripples over the turbine, which spins like a helix between bright blue pontoon floats. But it’s not floating. The electricity-generating rig is all underwater — anchored about 15 feet beneath the surface.

The Kvichak River in southwestern Alaska hosts the largest sockeye salmon run in the world, bringing in millions of dollars from commercial fishing and attracting sport fishers to one of the premier locations in the state. The river has provided subsistence for Alaska Native peoples for thousands of years.

And now it’s also home to a turbine that generates energy for Igiugig, an Alaska Native village of 70 people on the river’s banks. Iguigig is well south of the Arctic Circle, but the village is similar in many ways — including its energy situation — to remote Arctic settlements elsewhere in Alaska, and in northern Canada, Russia and Greenland.

“We actually find everything we need right on our front door,” AlexAnna Salmon, president of the tribal council in Igiugig, told ArcticToday. “We don’t have camps that we go to and have to subsist from; we do it right where we live.”

The river has sustained life in Igiugig for generations, and now it’s providing the community with renewable energy. The RivGen technology, developed by the Maine-based Ocean Renewable Power Company, generates electricity from tidal and river currents without using a dam.

Energy costs in the Arctic and sub-Arctic are among the highest in the world. Remote communities in the Arctic often run on diesel-powered microgrids, not connected to larger electricity grids.

Bringing fuel into communities and running the microgrids can be costly.

In Igiugig, diesel energy costs about 80 cents per kilowatt hour for residential and 91 cents per kilowatt hour for commercial energy, Salmon said. That’s six times higher than the average residential rate in the United States of 13.28 cents. In Alaska, the average is 22.26 cents.

The high cost of diesel threatens people’s ability to continue living in Igiugig, Salmon said. “If we could bring the cost of electricity down, or at least stabilize it, then we can continue to enjoy our high quality of life.”

Transporting diesel fuel can also be dangerous: There’s the risk of fuel spills as well as the effects of emissions from burning fossil fuels. Communities like Igiugig are witnessing firsthand the effects of human-caused climate change, and that was a big motivation in finding more sustainable sources of energy, Salmon said.

“We are a self-sufficient village with strong cultural and environmental values,” she said. “Bringing diesel in, risking all of the diesel transportation and then burning them in our generators, did not fall into the mission statement of upholding our environmental values.”

The shift toward renewable energy in this remote village has been a long, expensive and complicated process.

Igiugig’s journey began in 2004, when the village applied for an Alaska Energy Authority renewable energy grant. But the $750,000 grant would have all been spent on baseline studies and environmental reviews before any device could even be deployed, Salmon said.

“One million dollars can’t even get you to any kind of renewable energy out here in rural Alaska,” she said.

Next, Igiugig applied for U.S. Department of Energy efficiency grants, and several renewable energy companies competed for the award. ORPC rose to the top.

“We liked how they worked — they turned to the local knowledge and collaborated,” Salmon said. “They realized we’ve lived here on the river for 10,000 years, so we have innate ingenuity when it comes to working in these conditions.”

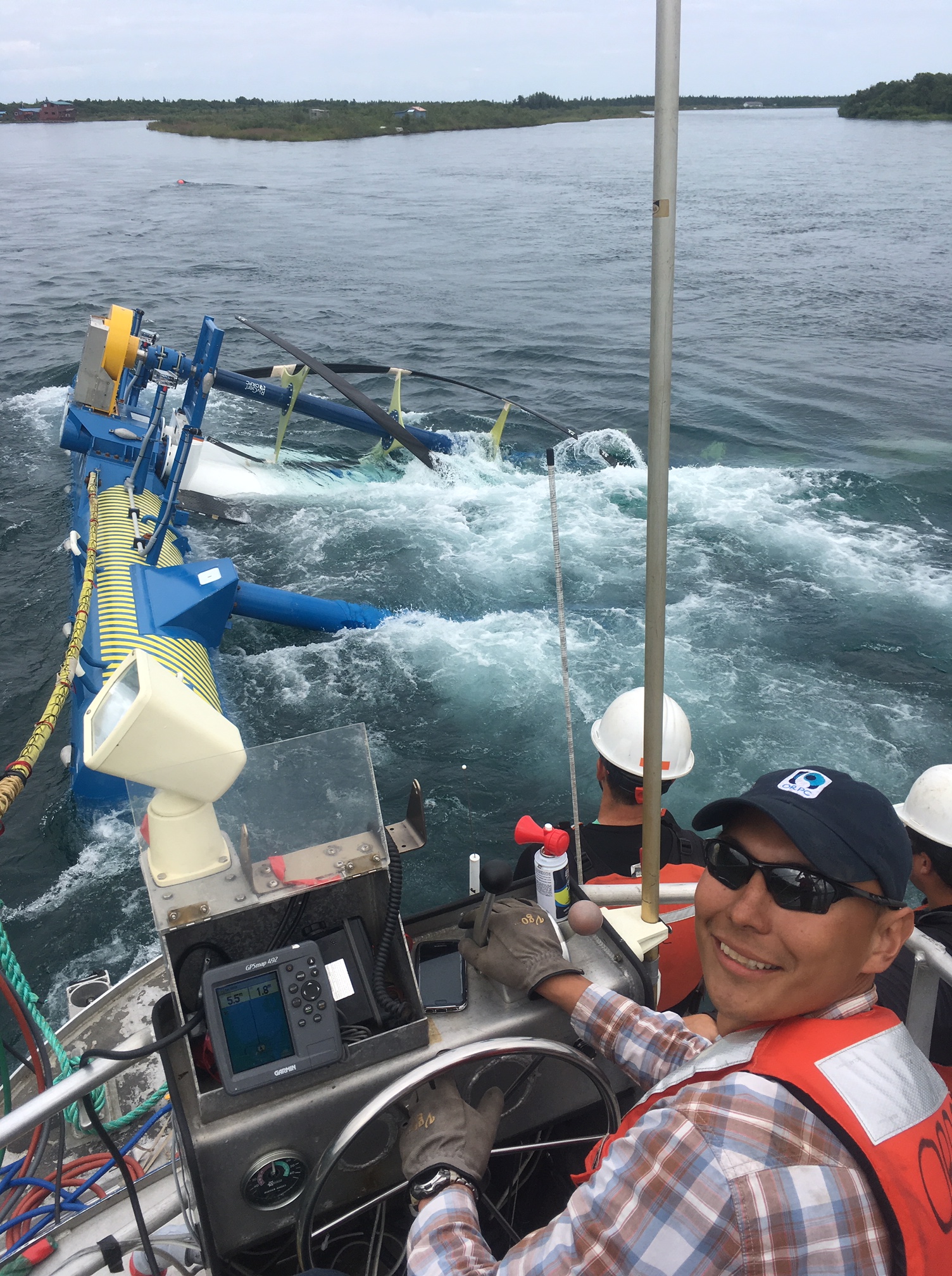

The first two versions of the turbines were deployed in the summer months of 2014 and 2015. After years of polishing the prototypes, including over the summer of 2019, ORPC officially launched the first commercial river turbine in Igiugig in November 2019, making this the first over-wintering river power project in the North.

In all, the project has cost $4.6 million, and the first turbine is capable of generating about half of the electricity Igiugig needs.

The ORPC turbine design was originally recommended by the U.S. Navy, John Ferland, ORPC’s president, told ArcticToday.

“We’re not a windmill in the water or a giant fan in the water,” Ferland said. “The shape of it is more akin to a paddle wheel.”

That design helps them adapt to different sites, including shallower water.

Renewable energy projects in the Arctic must withstand some of the most extreme conditions on the planet, including wind, ice and snow as well as months with and without sunlight.

The RivGen’s first test with ice came in January: coated in frazil ice, the turbine floated up to the surface of the river. But the anchors held, and after a few days of warmer temperatures, the turbine settled back down in the river and continued working normally.

In fact, the underwater environment can help the equipment withstand some of the harsher elements, Ferland said.

“In the North, it’s actually a good idea to be underwater,” he said. On land, there are wildly fluctuating temperatures and weather. But in the water, temperatures tend to stay in a narrower band.

Unlike solar or wind power, current power is not tied to weather or seasonal changes. “Because the river’s running all the time,” he said. “It’s a great technology for the northern latitudes to have.”

Benjamin Loeffler, research manager at the Pacific Marine Energy Center, was part of the team at Alaska Center for Energy and Power, at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, that helped Iguigig conduct environmental assessments and other studies.

The Kvichak River is a little unusual because the water runs clear from Lake Iliamna, Alaska’s largest freshwater lake. “Most Alaska rivers are pretty turbid; they have either glacial silt or sediment in them,” Loeffler told ArcticToday.

Igiugig is a good place to test and develop river technology like these turbines before making the final product more rugged to withstand debris and turbidity, he said. ACEP also has a permanent test site on the Tanana river near Nenana, in Interior Alaska, where a handful of other river turbine developers have been testing their devices’ abilities to withstand these conditions. Ice coming in and out of rivers can also be a challenge that will need to be overcome in some places, he said.

Another challenge is integrating renewable energy into diesel microgrids. The grids need a baseline of energy to operate, and without good batteries and energy storage for the times renewable energy is temporarily interrupted, it can cause the systems to run poorly or inefficiently.

“It’s harder to do things in remote Arctic locations, but the incentives and the need is higher also, and the cost of electricity you’re competing against is higher,” he said.

Loeffler sees systems like this as very promising for northern communities.

About 200 Alaska communities operating on microgrids are situated on or near rivers, he said. “It’s hard not to stand on the riverbank and see all that water moving by, and — man, there’s a lot of energy there. A lot of potential.”

Many communities with marine resources, however, aren’t able to build dams, for economic, environmental, or geographic reasons. That’s where the river turbines come in — and they can be steadier and more predictable than other renewable sources, such as solar and wind, Loeffler said.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, told ArcticToday last fall that projects like this make Alaska the “vision” for renewable energy all over the world, particularly in remote, high-cost areas like the Arctic.

“We’ve got more microgrids in Alaska than anywhere else, I’m told, in the world,” she said. “We’re the innovators, we’re the pioneers, we’re who everybody is looking at. Whether you’re looking for application in the Arctic or what you might be looking to do in other remote, isolated high-cost areas, Alaska is the go-to place.”

After Rick Perry, the former U.S. energy secretary, praised the Arctic’s oil and gas potential, Murkowski pointed out that the North is also leading with renewable innovation.

“The technologies that we’re building out, that gives us that edge,” she said. “We’ve got something to share with people; we’ve got benefits that we can export.”

Ferland says that other remote northern communities with marine resources want to see how the turbine in Igiugig fares. “We’re hopeful that the project in Igiugig will be that example,” he said, “that shows what can be done.”

Salmon put it this way: “If we can make this work on the Kvichak River in rural Alaska, then it can be deployed anywhere in the world.”

The turbine is placed deep enough in the river to allow boats to pass over it, and the studies done in Igiugig so far have shown no adverse effects on marine life. The larger fish swim around or above the turbine, and smaller fish can even swim through it.

“We are a salmon-based society,” Salmon said. “We had to make sure first and foremost, that this device did not harm our salmon — either the incoming salmon or the out-migrating smolt.”

Any social or economic developments in Igiugig must be compatible with their subsistence way of life, she said.

Environmental impact studies to make sure turbines would not affect marine life took time and money. Igiugig also purchased underwater video cameras to monitor how fish interacted with the turbine.

“But now we can confidently say that no fish were harmed in all the deployments that we’ve done so far,” Salmon said.

The cost of ensuring there weren’t adverse environmental effects came on top of the project’s mobilization costs — including shipping and installing the turbine — which Salmon called “exorbitant.” That can be a major challenge to building renewable systems in the North.

Refining a project like this was complicated, from figuring out what kind of anchor works best in the river to using local equipment and knowledge in installing and maintaining turbines.

But relying on local equipment and training local operators was a key part of the project.

“Our tribe has always been progressive and forward-thinking in how we can continue to live in our village independently, self-sufficiently. And for us to do that, we need to not be reliant on the outside world for all our needs,” Salmon said. “We need to be producing our own energy with the tools we have.”

Igiugig hasn’t only focused on the river power. They’ve also invested in other sustainable energy projects, from solar panels to energy audits on buildings.

“We don’t want all our eggs in one basket,” Salmon said. “We don’t think that’s security.”

The “ultimate goal” is transitioning to complete energy independence based on renewables, she said.

Paradoxically, because Igiugig remains largely closed down due to COVID-19 concerns, their energy needs have plummeted for the time being. However, they’re still planning to expand capacity for when they reopen.

Later this year, ORPC will install smart grid electronics and an energy storage system. And in 2021, they’ll lower a second RivGen into the river; the two devices together should provide about 90 percent of Igiugig’s energy needs, relegating diesel generation to backup only.

“We are small, but if the smallest person can do it in the harshest conditions, then it can be done anywhere,” Salmon said.