How researchers are using movies to tell the stories of Arctic science

The newly released documentary "Ice Edge - The Ikaaġvik Sikukun Story,” was a key part of the Indigenous-led research project in Alaska.

When scientists want to get the word out about research findings published in academic journals, the usual approach is to have sponsor institutions issue press releases and then wait for news coverage.

Increasingly, scientists are using a different approach: making movies.

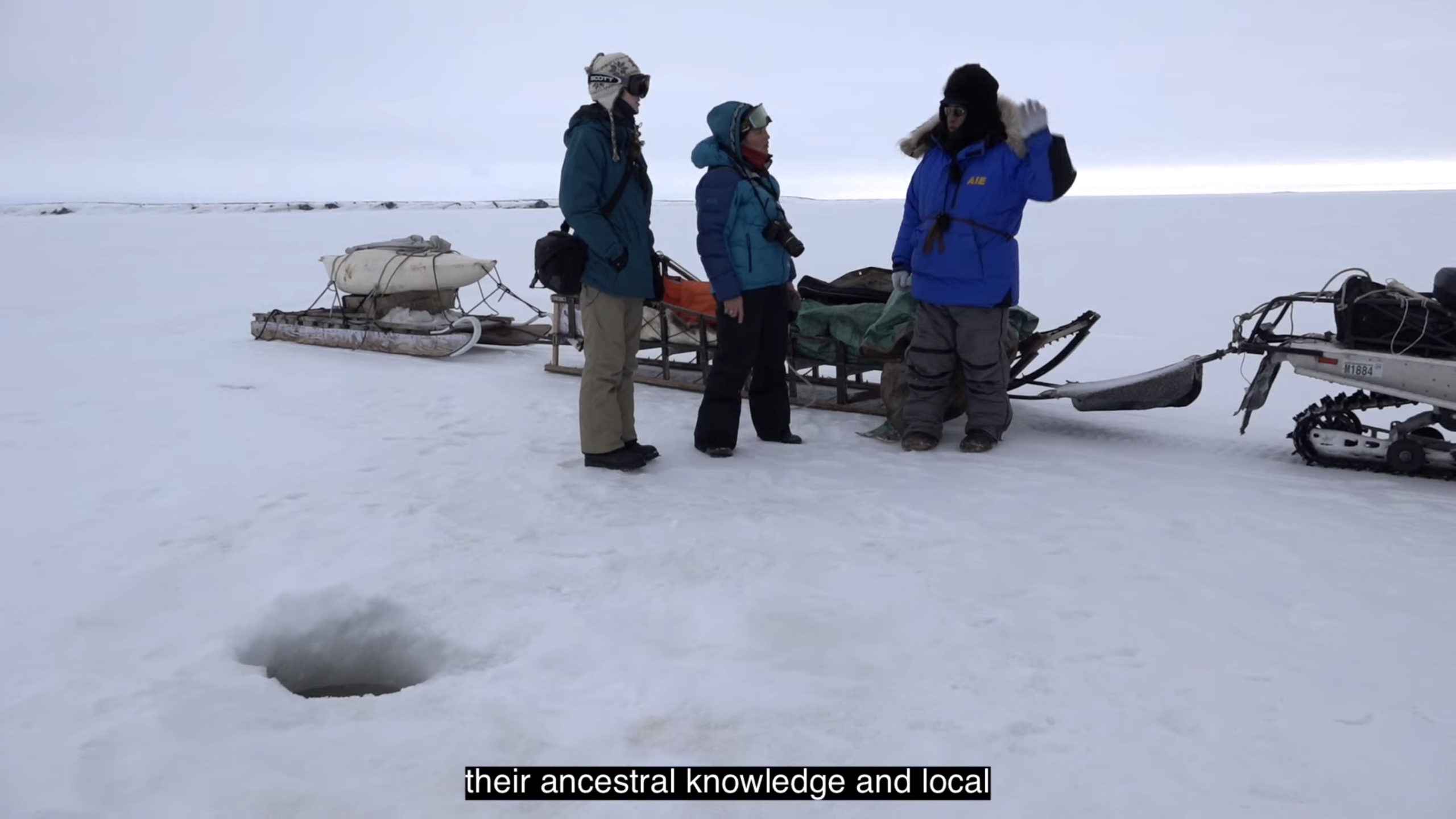

Filmmaking has turned out to be especially important for one particular Arctic science project: the innovative Ikaaġvik Sikukun program. Filmmaker Sarah Betcher was a key part of the team, which relied heavily on Indigenous knowledge and leadership in Kotzebue, Alaska to forge a path different from more conventional science projects.

She has now completed her full-length documentary explaining the project, a work called “Ice Edge – The Ikaaġvik Sikukun Story.”

The documentary shows how Ikaaġvik Sikukun, which has so far produced three published studies about seals, ice and how changes affect the animals and the community, differs from other Arctic research projects.

Instead of starting with a predetermined question, hypothesis and research plan to be carried out by scientists visiting the Arctic, the Ice Edges project started with something of an open slate. That flipped structure had Kotzebue community members — led by a committee of elders — coming up with the research questions, based on issues that were important to the people of the region. The Indigenous elders thus took the lead in crafting the fieldwork carried out by teams combining local people and visiting scientists.

The collaboration with visiting scientists was mutually beneficial, said one of the elders who guided the project.

“It’s always good to share our knowledge with others so that the world can see that we’re still involved in our traditional way of life,” Ross Schaefer said at the Jan. 27 online launch of the film.

That included collaboration with Betcher, who was got her own experience out on the ice and in a kayak in the water, he said.

The product of all that collaboration will be a wider spread of knowledge, he said. “It’s really good to share what we know and also learn from these folks a lot more about the world and have the world know that this is really happening t all of us, and it’s not stopping.”

The just-completed film does more than record the project’s science work. It actually helped shape that work, team member Donna Hauser, a marine ecology expert at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said during the documentary’s online launch party.

“As a scientist, this was the first time I’ve ever had a filmmaker following me around on a project — and having a camera at times when I wasn’t expecting it,” Hauser said with a laugh. But the presence of the camera, in turn, helped her connect her science work to the public, she said.

“I think that was actually an excellent opportunity to practice ways of speaking clearly and, you know, Being able to share the scientific process as it was happening,” she said.

Even though Hauser gets plenty of on-camera time, she does not deserve top billing, she said. “I still think that the elder advisers are really the star of the show,” she said.

Betcher, whose company Farthest North Films has an array of Alaska films available on YouTube, said she is trying to make this documentary as accessible as possible. Her other films have been used in schools, including at the college level, and shown at conferences, she said. This documentary, running an hour and 20 minutes, can be viewed in segments, which are already available on the Ikaaġvik Sikukun website or on YouTube (see above).

Betcher said she welcomes the opportunity to share her Ikaaġvik Sikukun work with students. “I’d be thrilled to know that the film was shown in classrooms,” she said.

Other projects that have used film to explain science in Arctic Alaska, too.

A three-part film series released in 2020, “After the Ice,” was produced through a partnership of academic scientists and the Bering Sea Elders Group. That project was funded by the multi-institution Study of Environmental Arctic Change, which is led by UAF scientist Brendan Kelly. The film series includes highlights of the indigenous consultations that were integrated into the 2019 Arctic Report Card released by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In the works is another film project that documents some permafrost research in northernmost Alaska.

Filmmaker Rick Minnich spent five weeks last August and September with Colorado State University scientists doing work in Utqiagvik, the northernmost U.S. community. The scientists are engaged in a project studying how permafrost thaw is linked to clouds and weather patterns. Minnich, an American filmmaker based in Berlin, said he is editing his film from that project – a work he has tentatively titled “The Big Thaw” – but has some short segments available on YouTube.