How tiny growth rings revealed the secret link between sea ice loss and tundra ‘greening’ and ‘browning’

“It’s not the same everywhere. The Arctic is a system that has complexities to it.”

As the Arctic warms and shrub growth continues expanding to higher latitudes, a paradox has emerged: Plants in many parts of the warming Arctic are withering.

Now a new study offers a potential explanation for the “browning” that is occurring in parts of the Arctic even as most of the circumpolar region is getting more leafy and woody.

The study, by an international science team and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, has tracked the relationship between dwindling sea ice and spreading Arctic shrub growth. It found that about 57 percent of shrubs sampled from around the Arctic grew more robustly as sea ice retreated over the past decades — and as summer air temperatures increased over the same decades. But a significant minority of the Arctic shrubs examined, 39 percent, had stunted growth as ice dwindles and air temperatures increased, indicating summer conditions that were too hot and dry for those plants to thrive.

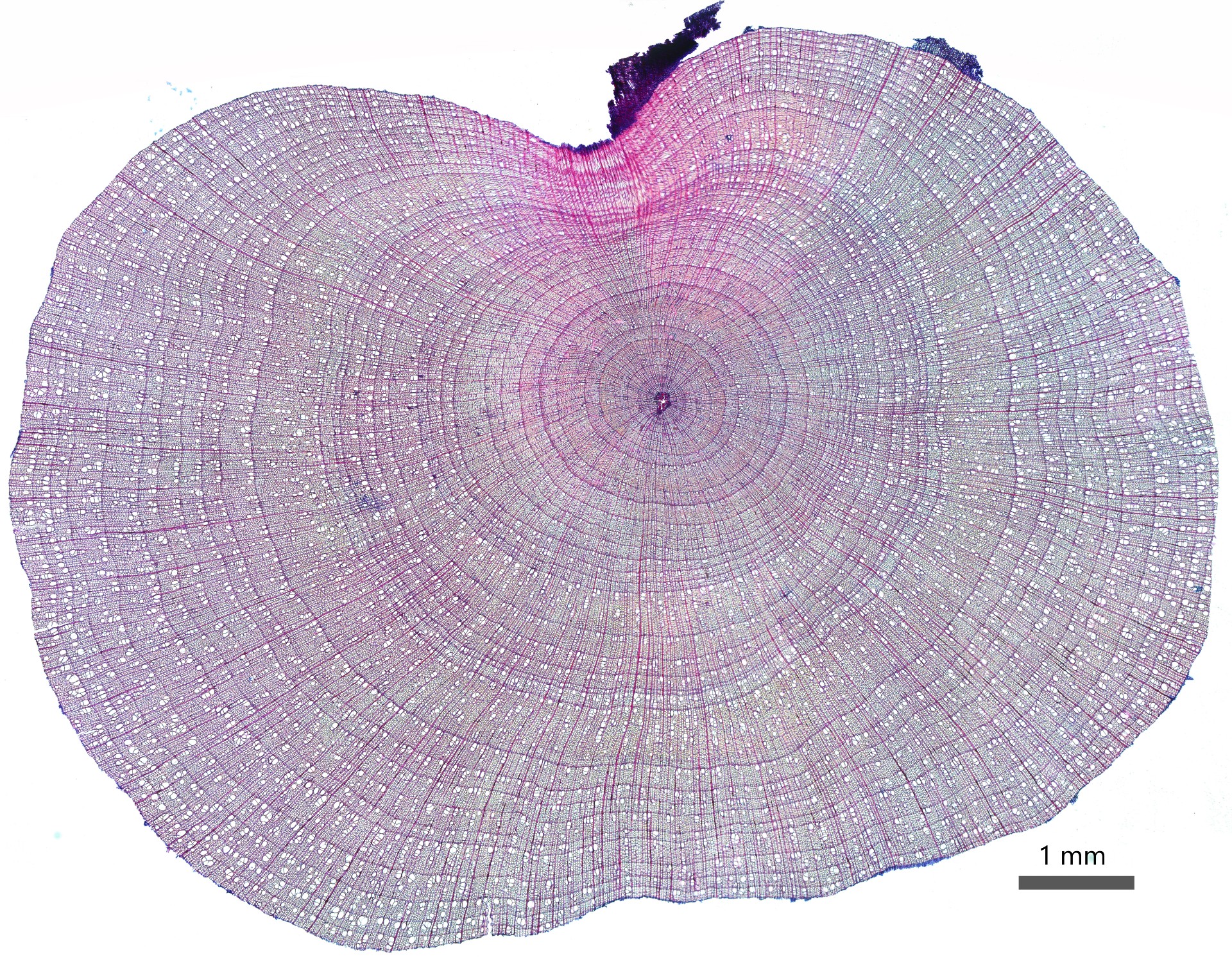

The study is based on the first application to Arctic shrubs of a technique long used in forests in lower latitudes: the analysis of tiny growth rings in the wood trunks of willows, birch and other plants from around the Arctic.

“There really is a shrub-ring fingerprint of the reduction in sea ice,” said co-author Jeff Welker of the University of Alaska Anchorage and the University of Oulu in Finland.

Just as the Arctic shrubs are smaller than trees — dwarf spruce or willow can be less than a meter tall even if it is 100 years old — the shrub rings examined in the project were much smaller than tree rings, too. Some are can even be microscopic. But when it comes to revealing growth rates and past climate conditions, the technique — known as dendrochronology — works works the same way.

[How tall tundra shrubs reveal the hidden presence of permanently thawed tundra soil]

The shrubs’ response to sea ice decline, seen by the varying widths of the rings, comes down to the availability of water in the soils.

In most places, the warmer air temperatures triggered by sea ice reduction increases precipitation, resulting in beneficial water conditions for the shrubs. But in other places, where shrubs were growing in drier or rockier soils or on well-drained ridges, the low ice-high temperature effect is a reduction in plants’ water availability.

“It’s not the same everywhere. The Arctic is a system that has complexities to it.” Welker said.

Among the places that are moist and where sea ice reduction is paired with increased plant growth is the tundra around the Toolik Research Station on Alaska’s North Slope.

Places that are dry or well-drained, where ice loss is linked to low shrub growth, include an area in western Greenland near the old Sondrestrom Air Base that is nicknamed “Sunny Sonde” by the visiting scientists. “It’s a bloody hot place and it’s getting hotter,” Welker said. There, and in places like that, more atmospheric heat that causes evaporation of moisture can mean shrub withering, similar to what happens when house plants do not get water, he said.

The shrub ring project was led by Agata Buchwal a Polish scientist who pursued the project as a Fulbright doctoral fellowship. For the fellowship, she was posted in Alaska from 2014 to 2017 — though she traveled elsewhere in the Arctic — and worked with Welker. There were several collaborators on the project from numerous institutions, many of them part of the University of the Arctic network.

Welker is the UArctic’s research chair, a position responsible for developing research collaborations and cooperation across the Arctic. This shrub project was one of those collaborations, he said.

Buchwal, who is now with the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznan, Poland, said the puzzling question of tundra “greening” versus “browning” inspired her to examine the link with sea ice. “Something is happening in the tundra biome and is happening pretty fast,” she said by email.

The newly published study built on previous work by some of her collaborators that examined the case of reduced shrub growth in warming western Greenland. That research produced a 2017 paper published in the Journal of Ecology. Buchwal said she decided to examine shrubs from various Arctic regions to see test the impacts of big climatic patterns. The “ground-breaking” moment was the discovery of a signal of sea-ice extent and “more surprisingly, that signal was divergent,” she said.

The new study found that the divergence between “increasers,” the shrubs that gained when sea ice retreated, and “decreasers,” those with slow growth, started in the mid-1990s and was most pronounced in younger plants.

The findings are important to the understanding of tundra browning, said Howard Epstein of the University of Virginia, an Arctic vegetation expert who was not involved in the project.

Scientists already knew, to some degree, that moisture plays a role in whether Arctic areas are greening or browning and that wetter sites “were typically more likely to support shrub expansion than drier sites,” he said by email.

“However, this paper makes the link between changing sea ice conditions, changing precipitation and soil moisture conditions and vegetation change,” he said.

Another “cool” aspect of the study was the analysis of the tiny shrub rings, a new aspect of the study of vegetation change at high latitudes, Epstein said.

Welker said further research into tundra shrub dynamics is “diving a little bit deeper into the mechanism of the water respiration” and examining the role of snow, an important part of the ecosystem. “Any changes in snow may be just as important as changes in temperature,” he said.

The divergence of tundra greening and tundra browning continues in the Arctic, according to the annual Arctic Report Card released last week by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As it has since 1982, the greening trend dominated in the Arctic, said the report card’s chapter on vegetation, co-authored by Epstein. In 2019, the last year for which data is available, tundra productivity rose substantially in the Arctic in general, the report card said. But the reduction in plant biomass that has been recorded in some areas over the last 15 years — the browning — “has emerged as an increasingly important phenomenon,” the report card said.

Arctic browning can happen both gradually over several decades, or it can happen abruptly, the report card said. Causes of abrupt changes include severe weather events, permafrost thaw, wildfire and insect infestations. That shows that Arctic warming can have dual effects on tundra vegetation, the report card said.

“While Arctic warming is likely to continue to drive greening, drivers of browning are also increasing in frequency,” it said.