Human activity takes a toll on Nunavik caribou habitat

Researchers at Université Laval say human activity in northern Quebec is damaging and reducing the extent of caribou habitat, and the health of the herds that migrate through Nunavik each year.

A new study attempts to quantify that impact by looking at how the animals have shifted their ranges as roads and mines are developed in the region.

The two main migratory caribou herds in Nunavik have seen their populations drop dramatically in recent years. The George River herd has plummeted from 800,000 animals in 1993 to just 9,000 in 2016, while the Leaf River herd has dropped from 600,000 caribou in 2001 to less than 200,000 today.

[How will climate change affect Arctic caribou and reindeer?]

Those herds are sacrificing parts of their habitat to avoid those disturbances, from about 2 percent of their summering grounds to a cumulative loss as high as 20 percent of their wintering grounds, the study says.

Every year, the George River and Leaf River herds embark on two long migrations to reach their summering and wintering grounds, covering a span of 1,000 kilometres.

Each spring, the caribou migrate north to their calving area in the Arctic tundra, where in June, the females calve and then continue on to their summering grounds in search of food.

In September, the herds move south to the wintering grounds where the boreal forest and taiga meet.

But along that route, the number of mining operations and projects that straddle northern Quebec and Labrador has doubled between 1990 and 2016, even despite the fluctuation of metal prices in recent years.

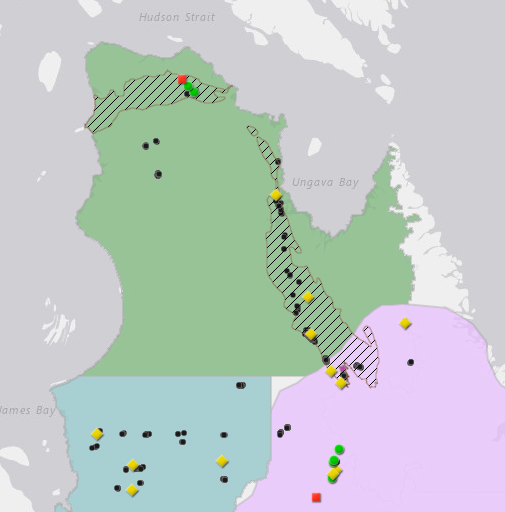

In Nunavik, there are only two operating mines — Glencore Raglan and Nunavik Nickel — though a number of other mineral exploration projects dot that region, known as the Ungava Trough, as well as the Ungava coast south into Labrador.

As caribou move farther away from human-inhabited areas, the impact is felt on Inuit communities, where the caribou harvest can represent the annual equivalent of $10,000 in income for a Nunavimmiut family.

The Laval researchers acknowledge other factors could also play a role in the herds’ declining populations. Those include an increase in predators to the region, like the grey wolf and the black bear, sport or subsistence hunting, extreme weather events and competition for resources among other herbivores, like muskox — all factors being studied by the Caribou Ungava research group.

The new data is presented in an interactive story map, produced by Laval’s Northern Sustainable Development Research chair, Thierry Rodon, and Caribou Ungava director Steeve Côté.

The interface allows viewers to see the region’s infrastructure, potential development sites and communities, as well as the range of the migratory caribou.

The project was presented on Wednesday, Dec. 13, to the Arctic Change 2017 conference in Quebec City.