Iceland fully reopens amid rising vaccinations and demand for tourism

The eruption of the Fagradalsfjall volcano may draw more tourists, while the resumption of a key Arctic conference brings decision-makers back to Reykjavik.

Iceland has relaxed all domestic coronavirus restrictions as its vaccination campaign for adults nears completion, officials announced last week.

The news means tourism, a major contributor to Iceland’s economy, will likely resume at a higher rate — and that a key Arctic conference is now planned to take place in-person this October.

The country no longer requires masks or physical distancing, and limits on public gatherings and restrictions on businesses’ operating hours have been lifted.

International visitors who have been vaccinated or had COVID-19 previously, as well as children under the age of 16, no longer need to take a COVID-19 test to enter Iceland, and they don’t need to quarantine unless they develop symptoms.

The health ministry announced the changes on June 25, with restrictions lifting the following day and the testing requirement ending on July 1.

“We are regaining the kind of society which we feel normal to live in and we have longed for,” Svandís Svavarsdóttir, Iceland’s minister of health, said in an announcement.

About two-thirds of adults in Iceland are fully vaccinated, and 87 percent have received at least one COVID-19 shot. All eligible Icelanders should be vaccinated by the end of July, the health minister said.

That means that vaccination plans and restrictions are now “completed,” according to the health ministry.

Iceland announced in April that it would open to vaccinated travelers with no quarantine required, making it the first European country to do so. Relaxing the rules further could mean more visitors to Iceland’s sites, shops and restaurants.

The pandemic dealt a critical blow to tourism in Iceland, as it did in many other countries.

[After years of over-tourism concerns, Iceland now has the opposite problem]

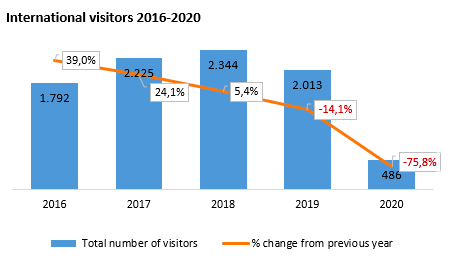

Iceland welcomed a record 2.3 million visitors in 2018, up from 459,000 visitors in 2010. That number declined slightly in 2019 to 2 million people, as the economy grew stronger and cheap flights on the now-defunct WOW Air ended.

Tourism remained a vital part of the economy, however, even outcompeting Iceland’s fisheries. The government of Iceland calls tourism “one of the main pillars of the Icelandic economy.”

But in 2020, the number of tourists dropped dramatically to 486,000 as the coronavirus spread and travel restrictions tightened. Unemployment among Icelanders rose as tourism plummeted.

In April, the International Monetary Fund said that “Iceland’s dependence on tourism has made it highly exposed to health, economic, and financial contagion from the COVID-19 pandemic.” That could mean Iceland will suffer a prolonged economic recovery, not returning to pre-COVID levels of GDP before 2026.

Iceland is no stranger to economic crisis. After the 2008 recession, Iceland’s krona weakened and the island nation became a more affordable destination for international travelers.

The 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajokull then drew a flood of sightseers, eventually growing to six times the population of Iceland itself, and Iceland’s tourism infrastructure began to strain under the the industry’s rapid growth.

Now, Iceland may return to the top of some travelers’ lists after the activation of Fagradalsfjall, a volcano that began erupting in March. The volcano, which is a short drive from both Reykjavik and Keflavik, could become a major tourism draw.

During the pandemic, the Icelandic government began investing about $12.3 million in national parks and tourist destinations, as well as plans to improve roads and harbors, the New York Times reported last fall.

The island nation hopes the investments will forestall some of the tourism strain seen in the past decade and capitalize on Iceland’s natural beauty — a major draw after many tourists stayed home last year — without spoiling it.

Tourists aren’t the only international travelers drawn to Iceland.

The Arctic Circle Assembly, an annual conference held in Reykjavik, went virtual last year because of the pandemic. But organizers announced this week that the conference will be held “in the traditional way as an in-person event” in October, with more details forthcoming.

Iceland has been widely hailed as a model for science-based COVID control, instituting various levels of restrictions as cases around the world waxed and waned over the past year and a half.

Iceland implemented a robust policy of testing, contact tracing, and quarantining. Preschools and primary schools, which were deemed high priority and relatively low risk, remained open throughout the pandemic.

Since the start of the pandemic, Iceland has seen more than 6,600 cases and a total of 30 deaths from COVID-19.

“We fully expect that we will continue to detect cases and that small clusters of infection may appear,” Víðir Reynisson, head of civil protection, said in the statement. “But we are confident that our contact tracing capabilities, with the public’s willingness to abide by both quarantine and isolation requirements, will prove sufficient to handle any new outbreaks.”