In a changing Arctic, a lone Coast Guard icebreaker maneuvers through ice and geopolitics

ABOARD THE USCGC HEALY IN THE ARCTIC OCEAN — Coast Guard Ensign Ryan Carpenter peered north through a front window of this 420-foot long ship, directing its bright-red hull through jagged chunks of ice hundreds of miles north of Alaska.

It was only the second time that Carpenter, 23, had driven the 16.4-ton USCGC Healy, one of the U.S. military’s two working polar icebreakers. He turned the ship slightly to the left in the sapphire-blue water, and a few seconds later, the ship’s bow rumbled through the crusty white ice floe at about 10 mph. Metallic shudders rippled throughout the vessel, a feeling that Arctic rookies often find unnerving.

Carpenter is part of an increasingly pointed U.S. strategy to prepare for competition – and possible conflict – in what was once a frosty no man’s land. The warming climate has created Arctic waterways that are growing freer of ice, and with China and Russia increasingly looking toward the region for resources, the United States is studying how many new icebreakers to build, whether to arm them with cruise missiles, and how to deal with more commercial traffic in an area that is still unpredictable and deadly.

Adm. Paul Zukunft, the Coast Guard commandant, recently warned that Russia and China are already encroaching on Arctic waters over the extended U.S. continental shelf. The region is about the size of Texas and rich with oil, minerals and other resources that could be extracted as technology improves.

Zukunft said last month in Washington that the situation in the Arctic could someday resemble the contentious disputes in the South China Sea, where China has built man-made islands and military installations over the objections of its neighbors. Russia already has made contested claims that stretch to the North Pole and possesses more than 25 icebreakers, with more on the way.

The next generations of Russian icebreakers aren’t being built just to transit polar ice but to fight in it. One kind of ship in the works, the 374-foot Project 23550-class, is designed to be nimble in this environment while carrying naval guns and cruise missiles. The Kremlin also has disclosed plans to build or expand numerous bases along the northeastern Russian coastline, north of the Arctic Circle, including on Wrangel Island, Kotelny Island and at Cape Schmidt.

Meanwhile, China also has arrived in the Arctic, sailing research and exploration vessels here while arguing that no nation has sovereignty over these waters and the natural resources below. Chinese military officials have said that sovereignty disputes in the Arctic could require the use of force, according to an assessment written for the Naval War College Review.

The Obama administration proposed building new icebreakers in 2015, citing the warming seas and concerns about Russia’s intentions. But the effort to do so has gained new attention in recent months. Despite President Donald Trump’s skepticism of climate change, he marveled at the power of polar icebreakers during a May 17 commencement speech at the Coast Guard Academy, and promised his administration will build “many of them.”

Zukunft said that a fleet comprising three new medium icebreakers and three heavy icebreakers would allow the service to retire its older ships and keep one icebreaker perpetually patrolling in both the Arctic and Antarctic.

The Healy was commissioned in 1999, but the other working polar icebreaker, the USCGC Polar Star, is more than 40 years old. It deploys each year to Antarctica, but crew members have resorted to searching eBay for some parts because they are so hard to find, according to Healy crew members familiar with the sister ship.

The cost of the new icebreakers is uncertain at this point. Estimates are often reported to be about $1 billion each because of the reinforced hull and robust engines needed to operate in ice, but Zukunft said he thinks it will be less. A report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine published in July recommended that a single class of four heavy icebreakers be purchased in one block buy to save money and suggested that time is running out to do so.

“The nation is ill-equipped to protect its interests and maintain leadership in these regions and has fallen behind other Arctic nations, which have mobilized to expand their access to ice-covered regions,” the report said.

A Washington Post reporter and photographer sailed on the Healy from July 28 through Aug. 6, arriving on a Coast Guard helicopter off Alaska’s Cape Lisburne and departing on a small seacraft in the port of Nome, Alaska. In between, the ship meandered at least 230 miles northeast of Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the United States, before turning back.

The Healy, which travels annually to the Arctic, deployed this year on June 27 from its home port in Seattle with about 85 Coast Guardsmen and 40 scientists. It will make several trips to and from the Arctic Circle this summer, with stops in Alaska port cities such as Seward to swap out scientists and gather supplies.

Missions on the Healy vary, based on what the scientists aboard need. On this trip, the ship carried members of the Coast Guard Research and Development Center as they tested unmanned boat systems among the ice floes, including an oil skimmer, a quadcopter and a 10-foot yellow vessel that was named the “Minion,” after the popular cartoon characters.

Scot Tripp, the chief civilian scientist on the mission, said that when he started coming to the Arctic in 2012, there was ice nearly all the way south to Alaska’s northern shores until June or July. That is no longer the case, prompting the service to evaluate what kind of new equipment it might need if a crisis emerges.

“There was no need for the Coast Guard to be up here,” Tripp said. “This was frozen, and now it’s not. So now there are waterways and cruise ships coming up, so you run into the possibility of disaster with one of those.”

Even with the warming climate, the Arctic environment is unforgiving. The summer water and air temperatures are about 30 degrees, and winds often howl at 30 to 40 mph. Coast Guard members work the decks in thick snowsuits, steel-toed boots and hard hats, and anyone leaving the Healy on a smaller seacraft used for exploration must wear a winter suit with a rubberized shell to extend how long they can survive if they fall in the water.

Officers piloting the Healy said that they do their best to avoid ice, but in areas where it is inevitable, it is considered safer for the ship to use the reinforced front of the ship to punch straight through it, rather than “shouldering it” and taking a glancing blow. Even then, sticky situations still emerge.

Ensign Taylor Peace, 23, who is on her second Arctic tour, said that last summer, the Healy spent four days wiggling out of an ice floe that wouldn’t let go of the ship, Peace said.

“No one flipped out,” said Peace, of Fairfax, Virginia. “You just keep trying. All you’re doing is waiting for the wind to change direction so it can relieve the pressure, or so you can at least make five inches in an hour.”

The harsh environment was on full display July 29, as the Healy carried out two consecutive missions on the water in a smaller seacraft. In the first, the Healy lowered a small landing craft carrying members of the scientific team to examine the usefulness of the Minion and other equipment as the drone boat bounced between craggy ice floes. The banana-yellow vessel, carrying solar panels and a camera, got stuck only after its battery died, prompting the crew to tow it back to the Healy.

“This is a good chance to try it in a harsh environment, coming out here to work these vehicles,” said Jason Story, a Coast Guard naval architect who designed the Minion.

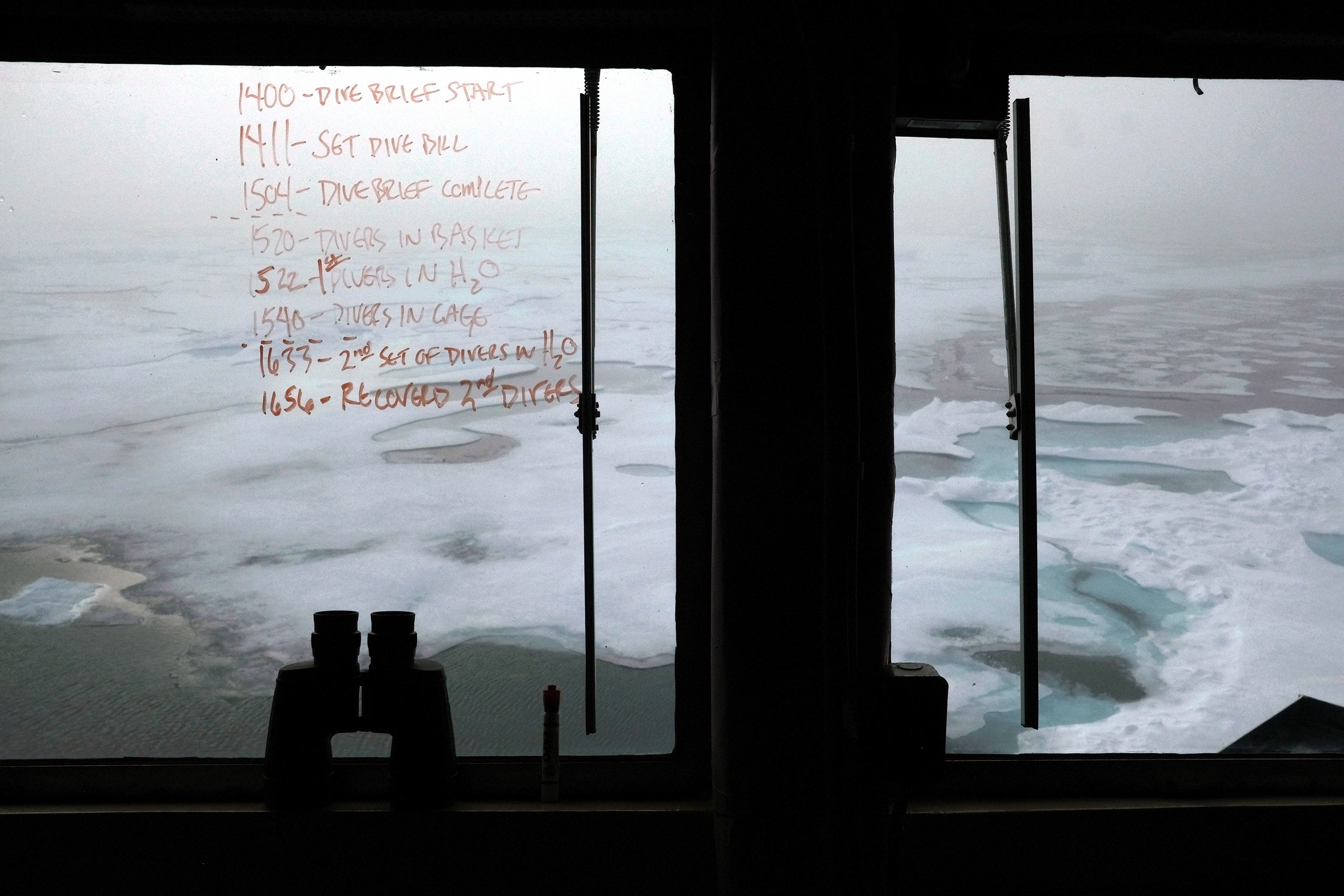

Winds picked up and fog thickened during the second mission of the day as divers marked a return to something that had not occurred in the Arctic since Aug. 17, 2006: Coast Guard ice diving. The long hiatus followed the deaths of two Healy crew members – Lt. Jessica Hill, 31, and Petty Officer 2nd Class Steven Duque, 26, – during an ice dive that a service investigation found was poorly supervised.

The Coast Guard subsequently started its own ice-diving school and made diving a primary occupation, rather than a collateral duty. The divers can perform maintenance on the ship, assist other vessels that are in trouble or perform salvage operations involving ships that have sunk.

“When we deploy to the Arctic, there is no bench strength nearby,” said Capt. Greg Tlapa, the Healy’s commanding officer. “No one is coming to save us. So, the more self-sufficient you are in terms of underwater inspection and hull repair, the less risk there is to a deployment.”

On a bone-chilling afternoon, teams of two divers dove among the floes while a third diver sat ready in case his help was required. The sea craft was anchored to a hulking piece of ice on the ocean’s surface.

The divers marveled at the clearness of the water and the crystallized ice – about 85 percent of the sea ice floating in the Arctic is beneath the surface.

“It’s like diving in outer space,” said one of the divers, Chief Petty Officer Chuck Ashmore. “I think that’s the closest comparison I could make. You’re seeing some just incredible structures down there.”