In Christmas letters to his children, J.R.R. Tolkien created a fantastic Arctic with echoes of Middle-earth

Like parents the world over, J.R.R. Tolkien dedicated considerable time and effort to making Christmas a joyful time for his young children. Yet this was a man whose rich imagination brought to life an entire world with thousands of years of legendary history; described different orders of creatures, wars and battles; even invented languages. So inevitably, his family traditions were something rather special.

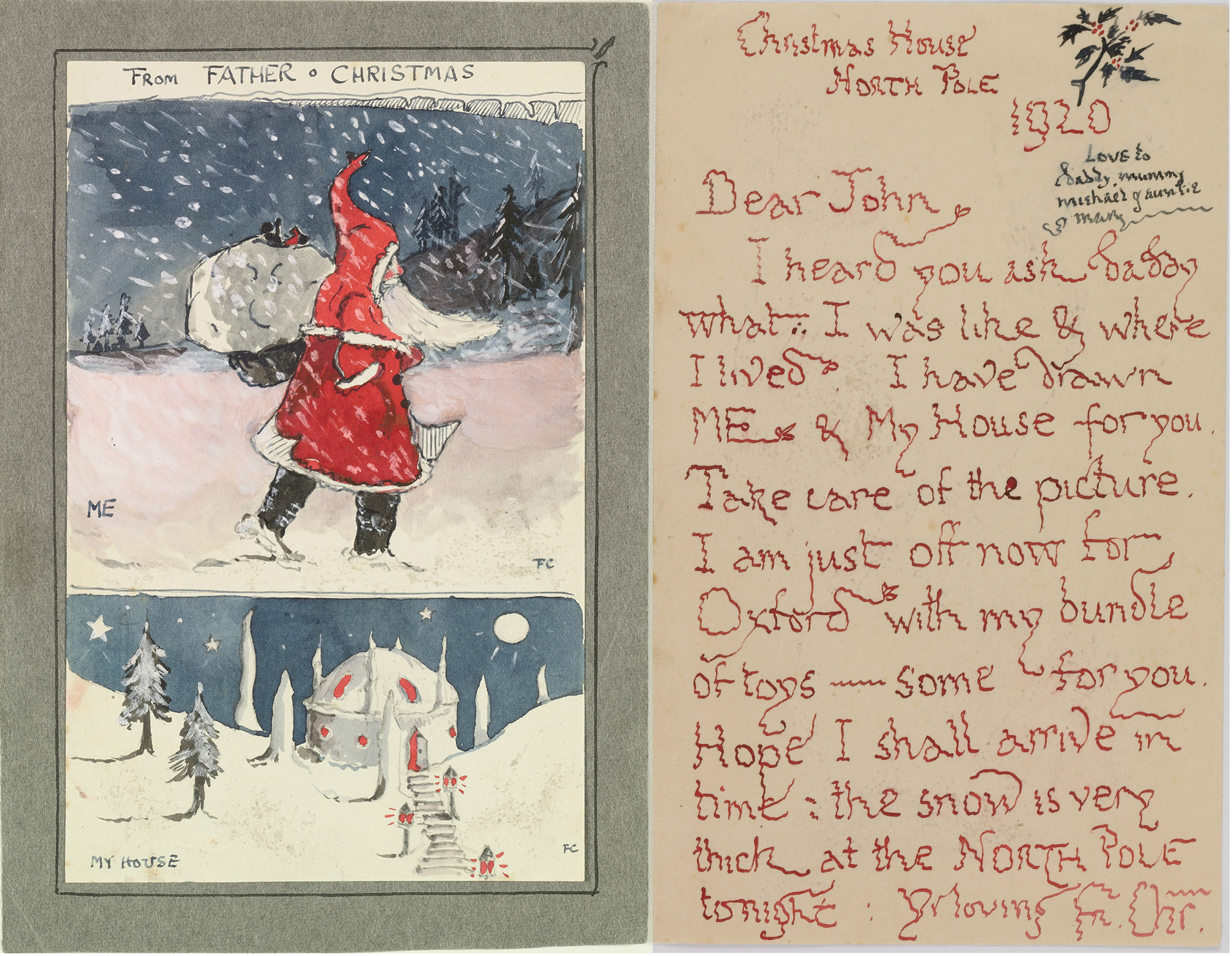

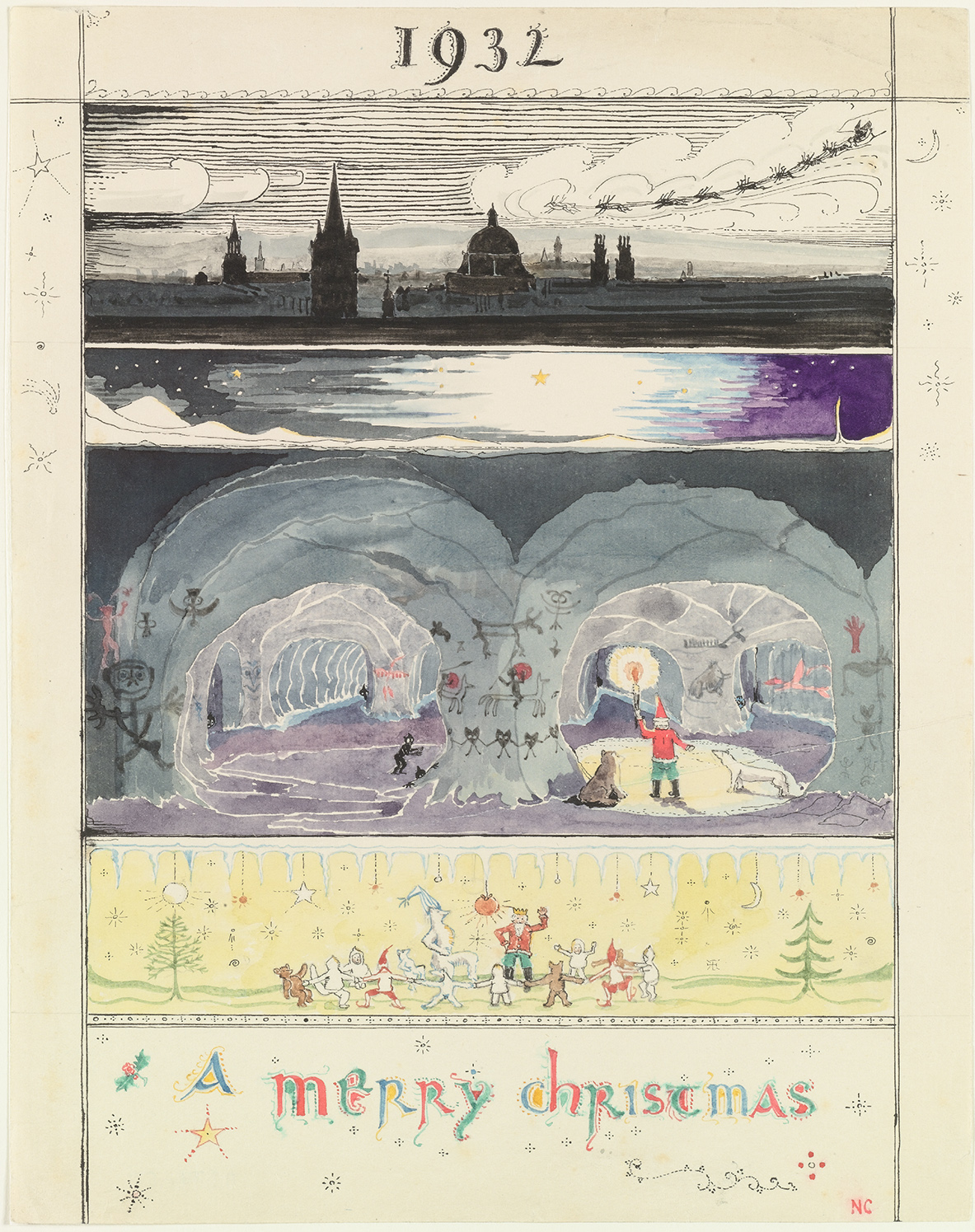

Every year, from 1920 to 1942, the Tolkien children – first John, and later Michael, Christopher and Priscilla – would receive a letter from Father Christmas. It would be written in his spidery hand (he would, after all, be a very old man) and illustrated with funny scenes from life in the North Pole. In 2018, the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford will exhibit the letters, alongside other manuscripts, artwork, maps, letters and artefacts from Tolkien collections around the world.

The American influence

Tolkien was not the first author to produce letters from Father Christmas for his children. Mark Twain famously wrote a letter from “Santa Claus” to his elder daughter, Susie Clemens. And although Tolkien retained the English name for his protagonist, there was a lot of popular American-derived folklore associated with his Father Christmas.

![The aurora borealis, 1926: ‘Isn’t the North Polar Bear silly? … [he] turned on all the Northern Lights for two years in one go. You have never heard or seen anything like it. I have tried to draw a picture of it: but I am too shaky to do it properly and you can’t paint fizzing light can you?’ (Copyright The Tolkien Estate Ltd, 1976.)](https://www.arctictoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/file-20171221-15915-og2s9q.jpg)

The idea of Santa Claus dressed in red and white, and riding a sleigh drawn by reindeer every Christmas Eve delivering presents to children, comes from perhaps the best-known poem in the English language: The Night Before Christmas. Written either by Clement Moore or Henry Livingston (the authorship is contested) in the 19th century, this classic American poem established Saint Nicholas, or Santa Claus, as we know him today.

The imagery of Santa Claus was enhanced by German-American illustrator Thomas Nast, who provided Santa with elf helpers and a toy workshop, and portrayed him living in the North Pole and in regular receipt of children’s letters.

Tolkien borrows freely from all of this American pop culture which, by the end of the 19th century, had migrated to Britain and was immensely popular. But he also takes his Father Christmas in different directions, gravitating towards his own mythology of Middle-earth, which was developing in parallel.

Old friends, and new

So of course we get elves in Tolkien’s North Pole. But despite the fact that these are diminutive, jolly elves with pointed hats (a far cry from those of The Lord of the Rings) they belong to different kindreds: Snow Elves, Red Elves or Gnomes, Green Elves – not unlike the High Elves, Silvan Elves and others in The Lord of the Rings.

Some of the Christmas elves were fierce warriors, giving the evil goblins a run for their money in battle. Indeed, the goblins themselves are precursors of the Goblins in The Hobbit, and later the Orcs. They live underground, they are keen on tunnelling, and they are a perennial threat to Christmas.

At the same time, Tolkien expands the Christmas mythology considerably. Father Christmas’s best friend (and regular rascal) is the North Polar Bear, whose funny antics are the focus of the early letters. Later on, his nephews, Paksu and Valkotukka (Finnish for “fat” and “white hair” respectively) provide further comic relief, and showcase Tolkien’s love for the language which influenced one of his own invented languages, Quenya, spoken by the Elves of Middle-earth.

A number of “aetiological” myths are also added: motifs that “explain” away things that happen in the real world of Tolkien’s children. So broken chocolates can be explained by the Polar Bear squishing them, and a bright light in the night sky is surely a glimpse of the gigantic Christmas tree in the North Pole.

Innocence lost

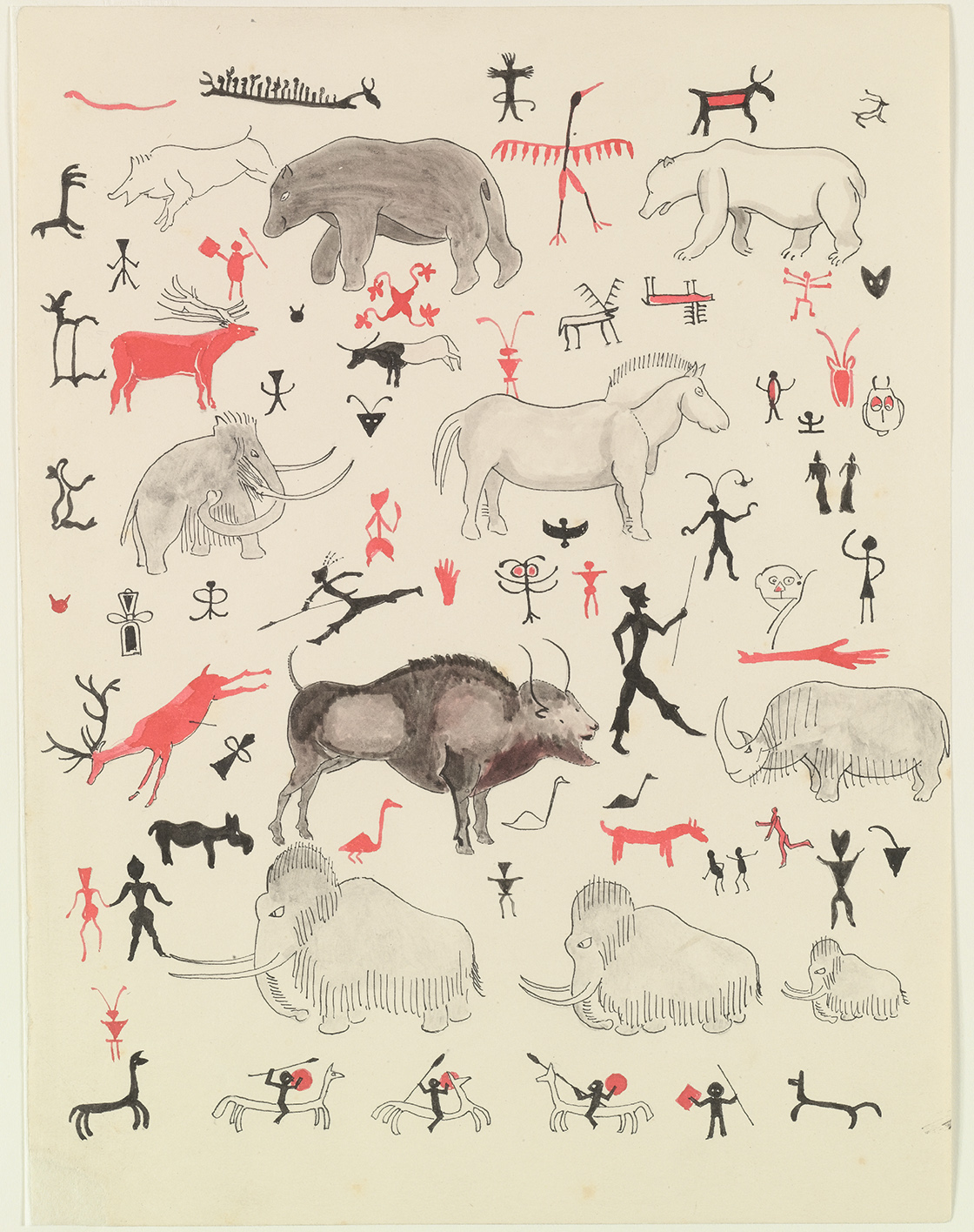

More details and innovations make this frozen world wonderful and intriguing. Father Christmas apparently has a tap in his cellar that “turns on” the Aurora Borealis; there is cave art by primeval men in the goblin caves, including depictions of mammoths and reindeer; and Snow-boys (the sons of Snow-men who live in the vicinity) get invites to parties in Father Christmas’s house.

Even more Tolkienian, we also get invented languages and alphabets. An elf called Ilbereth, who becomes Father Christmas’s secretary, sends the children a Merry Christmas message in elvish script, which is ostensibly a variation of Tolkien’s tengwar writing system, the same seen on the One Ring in The Lord of the Rings. And the Polar Bear gives us a sentence in “Arctic” (a version of Quenya) and introduces us to an alphabet he has devised based on goblin symbols.

The Father Christmas letters were published after Tolkien’s death in 1973, and their lasting popularity is, I would argue, due to the extended Christmas saga they create and the funny and moving father’s voice that comes through each of them.

The poignant “last letter,” when Father Christmas waves goodbye to children who are now “too old” to hang their stocking anymore, while the Second World War is raging, marks the end of innocence in more than one way. But the myth of Father Christmas lives on, and continues to be a favourite festive read of children all over the world.

Dimitra Fimi is Senior Lecturer in English at Cardiff Metropolitan University in Wales.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.