In the Arctic Ocean, plankton grows where coastal sediment flows

Receding sea ice and the impact it has on Arctic communities is often held up as the consequence of a warming climate. Research published this month in Science Advances, however, provides evidence that sea ice loss itself opens the door to potentially dramatic changes in the biological makeup of the Arctic Ocean.

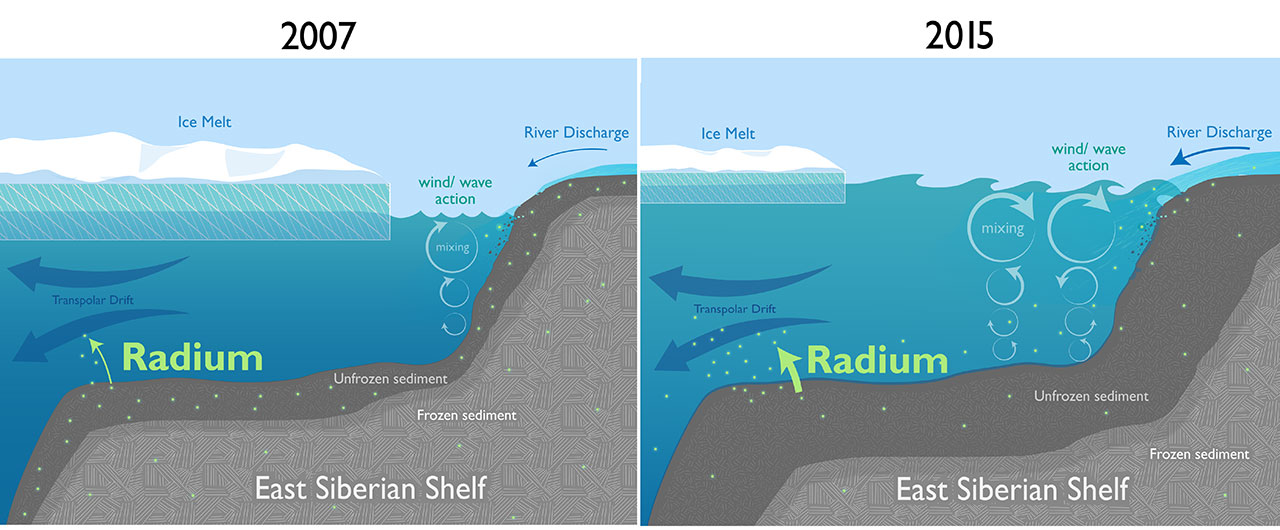

The research, conducted in 2015 in the waters of the East Siberian Shelf, notes that as sea ice levels decline, the open water it leaves behind allows more waves to be generated. These waves, it suggests, stir up sediment along the shallow coastal fringe ringing the Arctic Ocean.

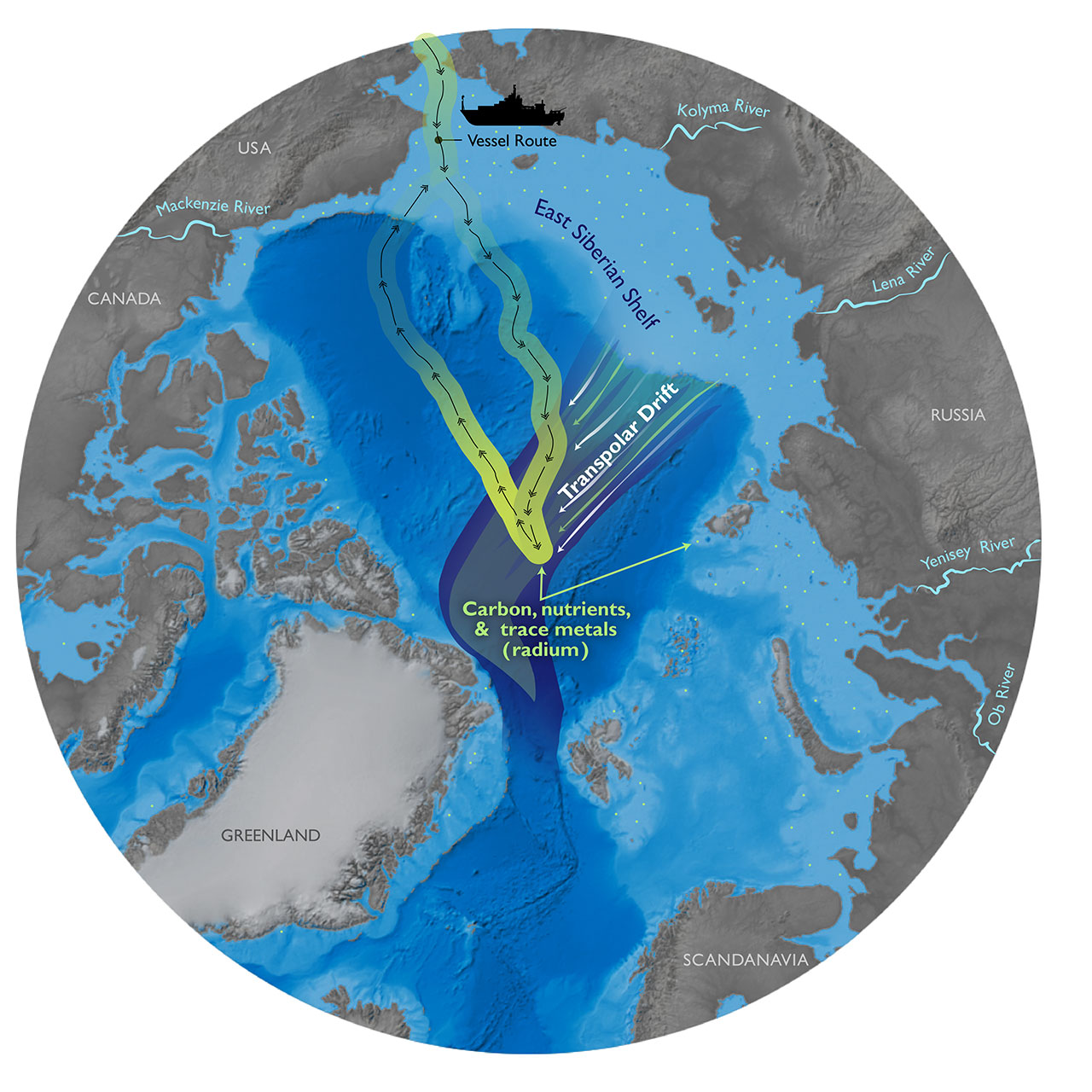

This sediment, containing things like plant and animal species, carbon, nutrients and trace metals, is then transported into the open ocean, where it could contribute to the growth of plankton.

Because plankton forms the basis of maritime food webs, changes to its living conditions set the stage for an alteration in the makeup of marine life in the Arctic Ocean, including an increase in the number of fish living there.

Scientists can track the direction, source, destination and amount of material from land using radium-228, a naturally occurring element only found in soil but quickly dissolved once in water. In this case, the team conducting the research compared their measurements with the first measurement of radium-228 in the Arctic Ocean, taken by another research group in 2007, to determine that the amount had doubled during the period.

By looking at the movement of sea ice and comparing it with the concentrations of radium-228 they recorded, the scientists determined that it was most likely being transported from the northern coast of Russia by a current known as the transpolar drift. Other Arctic Ocean currents may be transporting sediment from other coastal areas.

And while the research indicates that the primary source of the radium-228 is sediment from the continental shelf, it also identifies other potential contributors all linked to warming temperatures in the region, including coastal erosion and thawing permafrost.

Although the authors of the paper are confident that sediment is entering the Arctic Ocean, and that it stands to have a potentially significant impact, the amount of information currently available is limited, meaning more studies will be required before a full picture can be drawn.

“Continued monitoring of shelf inputs to Arctic surface waters is therefore vital to understand how the changing climate will affect the chemistry, biology, and economic resources of the Arctic Ocean,” they write.