Inside the U.S. Coast Guard’s unusual winter mission to the Arctic

The only functional U.S. icebreaker reached the northernmost ever for a U.S. surface ship on a winter mission.

Before noon on Christmas Day, the heavy icebreaker Polar Star reached the latitude of 72 degrees 11 minutes North — the furthest north a U.S. surface vessels has sailed in winter — before turning to head south for a port call in Dutch Harbor, the U.S. Coast Guard said.

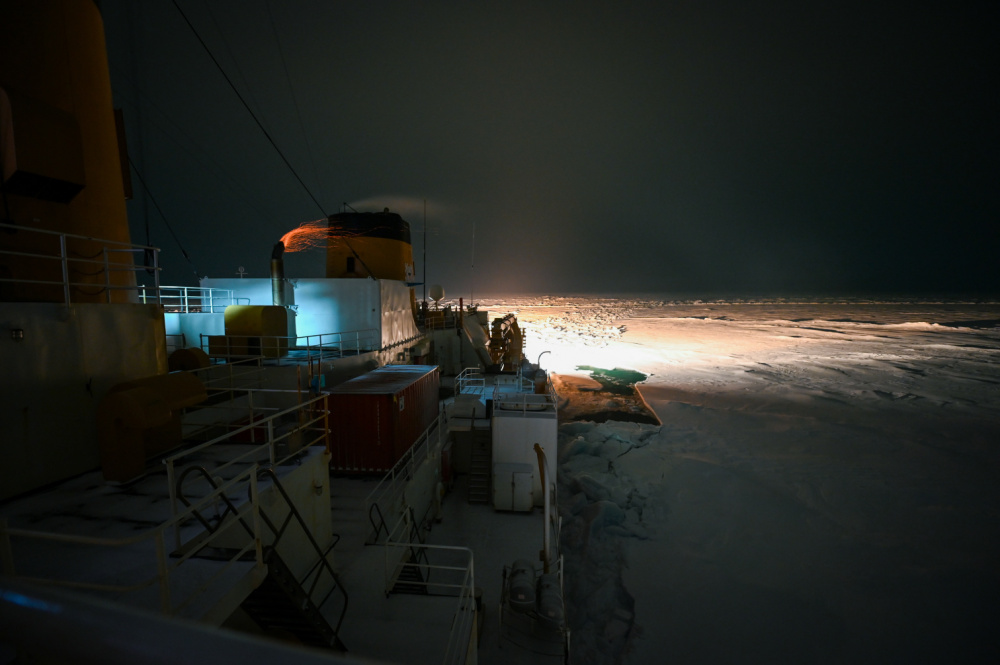

By the time the ship reached its turnaround point, about 80 miles away from Utqiaġvik, Alaska, it was sailing in complete darkness — something unusual for the crew of a ship that usually operates in year-round daylight of Antarctic summer while the Arctic is plunged into polar night.

Those milestones come as part of a rare winter Arctic mission for the U.S. Coast Guard, which — with few polar-capable icebreakers remaining in its fleet — has mostly operated in during polar summers in recent years.

Polar Star’s journey north began weeks earlier. It left the home port in Seattle on December 4, taking an indirect path north and then veering left to reach the maritime boundary line. The nation’s sole heavy icebreaker then headed north through the Bering Strait.

“We just went straight north on the 168th meridian, which is essentially the boundary line between the U.S. and Russia,” Capt. William Woityra, commanding officer of the Star, told ArcticToday. The ship was close enough to see the Russian fishing fleet operation on the other side of the boundary line.

For seven or eight days in the far north, he said, very hard, thick ice grated against the ship’s hull. “It sounds like a perpetual car crash,” Woityra said. “Like it’s twisted metal and shattering glass, just screeching as ice drags along the side of the hull.”

Thick ice, high winds, low temperatures, turbulent seas, a nearly total darkness that obscured navigation — all of these challenges are intended to familiarize the crew with working in Arctic winter conditions.

“This is no joke. This is truly varsity-level operations,” Woityra said. “The ice, the winds, the darkness, the storms are all incredibly challenging.”

Another purpose of the mission is to deter illegal fishing in U.S. waters.

Typically, the Russian Border Guard does more to monitor and prevent incursions from illegal fishing vessels in the region — especially in wintertime — so this mission is an opportunity to “be that presence for the United States and defend our exclusive economic zone and our resources from illegal fishing,” he said.

It also presented an opportunity to “get involved in a much broader geopolitically charged environment,” Woityra said.

Asked if the close patrol to Russian waters was a show of strength to Russia in particular, Woityra responded, “This entire mission, more broadly, is a message to the world. And I think you can infer that the other Arctic nations, and other nations that are operating in the Arctic, maybe have taken the United States for granted.”

He hopes the mission shows that the U.S. takes its status as an Arctic nation seriously, he said, and has the ability to operate in the Arctic year-round.

Woityra was part of the mission to the Bering Sea in February 2001, and other trips have also ventured far north at warmer times of the year. The heavy icebreaker Polar Sea, which is no longer operational, went to the North Pole in 1993, and the medium icebreaker Healy has also traveled to the North Pole.

“But this is by far the furthest north that any U.S. surface ship has gone in winter months,” Woityra said.

Even before it reached its northernmost point, Polar Star encountered difficult conditions, with sea swells reaching up 20 or 25 feet high at times. In those stormy conditions, most of the crew became incapacitated with seasickness, focusing only on keeping the ship headed in the right direction.

Sea ice in the Bering was slow to form this year, Woityra said. “That’s especially dangerous because there’s more open water, there’s more wave action, there’s more freezing spray.” The sea spray blows onto the ship’s hull and freezes in place, throwing the vessel off-balance and putting it at risk for capsizing.

The Star’s crew used hammers and axe handles to break off a two- or three-inch coating of ice from the hulls once they reached calmer frozen waters. But, Woityra said, “if you were stuck in open water in a storm like that, it’s a very, very hazardous condition.”

In the frozen expanses of the Chukchi Sea and Arctic Ocean, the crew encountered sea ice up to four feet thick, but it was a different quality than ice conditions seen during the ship’s annual Antarctica mission. The trip to resupply McMurdo Station usually takes place at the same time of year, during the Antarctic summer.

“In Antarctica, because the temperatures are a little bit warmer, the ice is a little bit softer — it makes more of like a slushing noise. In the winter, it’s a completely different experience,” Woityra said. In addition to the rending noise, the ship shudders as it pushes against the ice, making it difficult to focus or sleep.

“We know that we’re safe, but it’s really kind of an unsettling feeling,” he said.

Another challenge is the darkness. That far north, the dusky light looms on the horizon for about an hour each day, before plunging back into total darkness. It is difficult to know where to cut a path through the ice with such low visibility. The crew has to rely on searchlights and radar, which extend only a couple of miles ahead, to navigate most of the time.

On the second and third rounds of the mission, planned for the next month, the crew expects colder and harder ice but more sunlight.

“When we leave Dutch Harbor, we’re going to head north again, and look to find some more good ice to get into,” Woityra said. He plans to return to the maritime boundary line.

“The ship is up to the mission. We really proved that in this first stage,” he said. “But I will say the ship is starting to show her age. The crew is just working around the clock just to keep the ship running.”

On New Year’s Eve, the Star came to a stop in the ice, and the crew had to replace blown diodes and resistors on the propulsion generator rectifiers. “These are parts that simply don’t exist anymore. We’ve got a few boxes of them on the shelf, but when they’re gone, we’re out of luck,” Woityra said.

Equipment like that will likely be replaced during the $75 million service-life extension planned to begin this summer. “But ultimately, the only real solution is the [new] polar security cutters,” Woityra said. “Construction is supposed to start this month, and hopefully we’ll see one in the water here in the next four years.”

The 44-year-old Polar Star is the nation’s only heavy icebreaker, and currently the only functional vessel in the U.S. polar icebreaker fleet. Healy, the only other operational polar icebreaker, is currently undergoing repairs after an electrical fire cut short its summer mission in the Arctic. If Polar Star encounters significant issues in the Arctic ice, it will have to call on partners for rescue.

Usually, Polar Star heads south, not north, each winter. But the pandemic sharply reduced activities at McMurdo, rendering resupply by ship unnecessary (and, during the pandemic, potentially risky).

The pandemic has also affected spirits on the trip — but not in the way one might think. The crew members, who were quarantined and repeatedly tested before the mission began, have become unusually close in the Polar Star “bubble.”

“I’m so happy to be on the ship with these people in one gigantic bubble,” Woityra said. “Life absolutely feels normal.” It’s going to be difficult, he said, to return to Seattle in February and “go back to the pandemic lifestyle.”