Inuit leader at COP26 calls for Arctic shipping to be cleaned up

Lisa Koperqualuk called for ban on the use of heavy fuel oil.

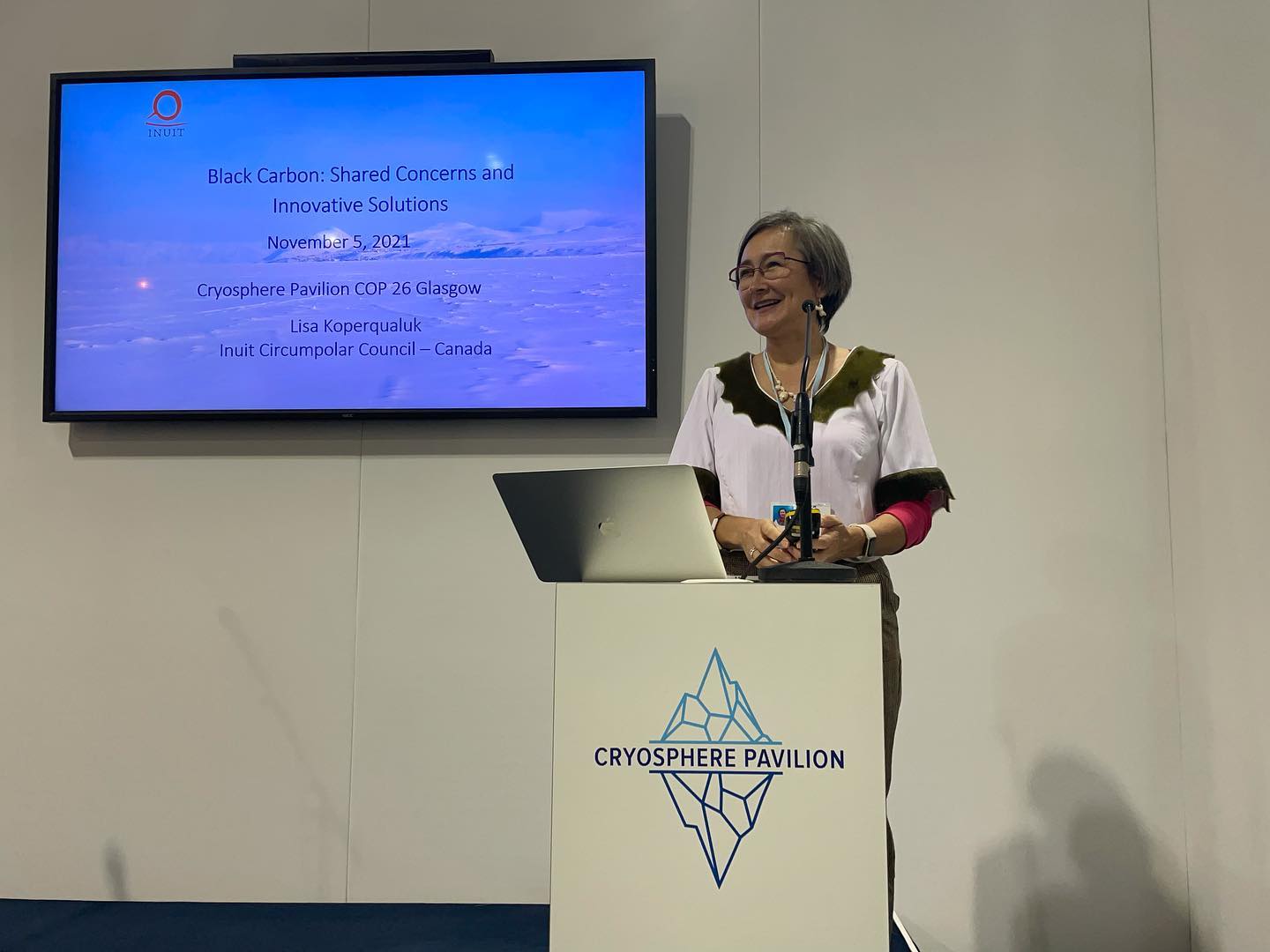

As representatives from countries and organizations around the world have descended into Glasgow, Scotland, to address climate change, Lisa Koperqualuk took to the stage at the summit to speak about an issue that particularly affects the Canadian Arctic: black carbon.

Koperqualuk is a vice president of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, or ICC, and one of the representatives from the organization at the United Nations conference on climate change, known as COP26.

“We can take days and days to actually sit down together and talk about it, that’s how important [black carbon discussion] is,” Koperqualuk said in her speech.

Black carbon — also known as soot — is emitted by ships operating in the Arctic that burn heavy fuel oil. It increases the temperature of the air surrounding it, and when it settles on ice, it makes the ice darker and less reflective, which in turn makes it melt faster.

Predictions that Arctic shipping could increase suggest this problem could grow.

Koperqualuk said she wants stronger measures in place to ban the use of heavy fuel oils used by ships going through the Arctic. Currently, the International Maritime Organization, or IMO, has approved a phased-in ban on the use of heavy fuel oil in the Arctic that would fully come into place in 2029.

Both the Nunavut and federal governments have opposed an immediate ban on the use of heavy fuel oil in Arctic waters, saying that such a ban would increase the cost of living in remote communities that depend on goods being delivered by sealift. One study concluded that the average Nunavut household would pay an additional $1,400 a year if the fuel were banned.

But the ICC and conservation groups say that a ban that’s phased in by 2029 is too weak.

In an email to Nunatsiaq News, Koperqualuk said the cost of transitioning to cleaner shipping fuels must not be put on communities. A transition fund for Arctic shipping established by the federal government is the best solution, she said, adding that investing $15 million over three years should be enough to offset any increased costs.

At a COP26 event Nov. 5 that focused on black carbon emissions in the Arctic, Koperqualuk described these challenges and spoke of the need to include Inuit in decision-making for shipping decisions in the Arctic.

“We’re speaking out on behalf of Inuit and saying, ‘Come on, stop using black carbon,’” Koperqualuk said.

She said the purpose of this speech was to raise awareness about who Inuit are, where they live and the impact black carbon can make on daily life in the Canadian Arctic.

“It can impact our culture and our language,” Koperqualuk said.

Koperqualuk said her organization made another step forward in its advocacy efforts last week, when the ICC became the first Indigenous organization to receive consultatory status with the IMO. This development will help the ICC be more involved in the decision-making for the shipping in the Inuit homeland.

“We can move forward in engaging with the IMO and have our voice heard,” she said.

COP26 runs until Nov. 12.