Inuit oral tradition takes center stage in new account of Franklin expedition search

Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition

By Paul Watson; W.W. Norton, 384 pages, $27.95.

Some books come with a soundtrack. With “Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition,” it’s hard not to hear the arching baritone of the late Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers keening about “the hand of Franklin reaching for the Beaufort Sea.”

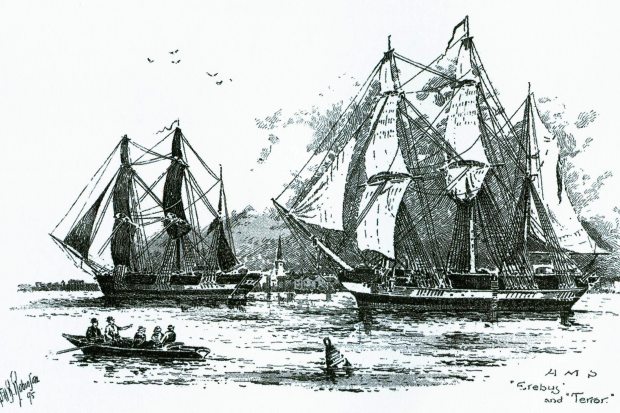

It’s a chilling image, given our knowledge of how Britain’s Sir John Franklin set out in 1845 with two ships and 128 men to seek an open trade route through the Arctic to the Pacific — and disappeared.

Not until 2014 and 2016 were the Terror and Erebus finally discovered, sitting upright on the ocean floor, the culmination of decades of work by dozens of searchers.

Paul Watson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, tells how Inuit lore, British pride and modern technology often worked at cross-purposes, and also how people, sometimes for no logical reason, became obsessed with the ill-fated expedition.

“Ice Ghosts” is in three parts: the expedition, the initial search and the modern-day attempts. Drawing only from historic documents for parts one and two, Watson’s account is as exhaustively detailed as one would expect from an ace reporter but also, understandably, a little lifeless.

Franklin was desperate to repair a tarnished reputation when he persuaded the Royal Navy to let him lead a third attempt to discover the lucrative trade route.

When the ships failed to return, Lady Franklin was relentless in demanding and often funding search expeditions. But bad luck, a dismissiveness of Inuit accounts and the vastness of the Arctic led to failure. With Lady Franklin’s death in 1875, it appeared that the mystery would remain.

[How Inuit knowledge helped searchers find the wrecks of Franklin expedition ships]

But the search and Watson’s writing are reinvigorated in part three. In Watson’s long relationship with an Inuk named Louis Kamookak is a deeper message revealed.

Kamookak was a boy in 1966 when he heard his grandmother’s stories of finding strange metal objects. He became fascinated with the mystery of Franklin and later began gathering an oral history of various elders’ accounts. Watson’s depiction of this work lends spiritual and physical insights into native life in the extreme conditions.

As Kamookak listened, he became convinced that native people knew what had happened to the ships. His work was patient, exhaustive — and discounted by the outside world.

Later searchers brought technology to the hunt, and indeed, the ultimate discoveries were a result of scientific advances (as well as some hardy scuba divers).

Yet mysteries remain: What exactly caused the ships’ demise? Was there mutiny or heroism? Debates continue.

But the ships’ locations vindicated what Kamookak had learned from the elders. Watson’s deeply felt understanding of that work heightens Kamookak’s sad satisfaction while enacting, at book’s end, an ancient rite over the sunken Erebus.

“Ice Ghosts” documents what happens when cultures collide. Or perhaps more pointedly, when one culture feels superior for no better reason than pride.

And Stan Rogers’ voice builds again: “Seeking gold and glory, leaving weathered, broken bones/And a long-forgotten lonely cairn of stones.”