Lead poisoning probably didn’t doom the Franklin Expedition

Comparisons of the remains of members of the Franklin Expedition with their Royal Navy contemporaries elsewhere show high levels of lead were common amongst sailors of the day.

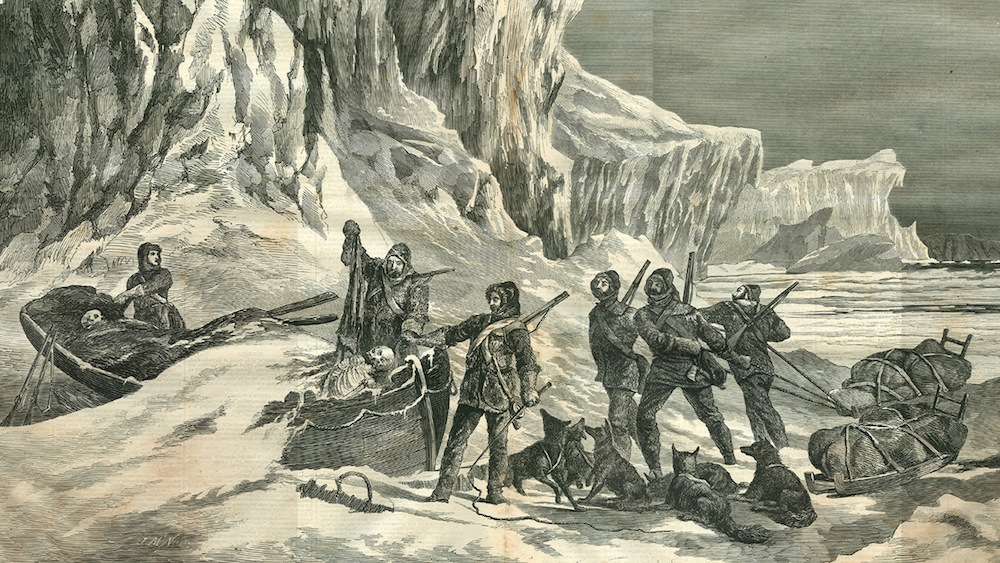

Most of those familiar with the Arctic will need no introduction to the fate of the Franklin Expedition. But what remains a mystery is the series of events that eventually lead to the deaths of all 129 souls who were aboard the Erebus and the Terror when the expedition’s two doomed vessels froze into the ice of the Northwest Passages in September 1846.

One long-running theory has been that the ultimately disastrous decisions made by the expedition’s leaders, culminating, in April 1848, with an order to abandon the ships and seek help on foot to the south, had been clouded by madness brought on by lead poisoning after consuming food from tin cans sealed with lead soldering, or possibly by drinking water that had been tainted by lead-lined containers.

Although evidence has been mounting against this theory, it has been hard to put to rest once and for all. In part, this is because the sheer volume of the exposure is hard to ignore: Each ship began the expedition supplied with some 8,000 cans of food, which was to serve as the expedition’s primary food supply.

Another persistent argument suggesting that lead poisoning played a role is the fact that the levels of lead found in the remains of Franklin Expedition members were indeed elevated — though this was in comparison to modern individuals and contemporary Inuit, note the Canadian authors of a paper published in PLOS One.

[Britain transfers Franklin’s shipwrecks to Canada, Inuit]

Exposure to lead was far more common in 19th century Britain than it is today, or amongst the Inuit of the day. To be accurate, a comparison would need to look at individuals with similar historic or geographic profiles. A comparison of the remains of contemporaries, on the other hand, should show whether one group had been exposed to extra lead at some point.

To find out whether this was the case for the members of the Franklin Expedition, the study looked at two different groups: expedition members who died before the two ships reached the Northwest Passages and Royal Navy sailors who died during the same era.

In the first comparison, the scientists measured the levels of three Franklin Expedition members who died and were buried while the ships were wintering over in 1845-46 on Beechey Island, Canada, with members of the expedition while the ships were frozen in ice. If the members of the expedition were slowly being poisoned by the food they were eating, the levels of lead measured in the remains of those who died earlier should have been lower. This was not the case.

[The Week Ahead: Terribly binge-worthy]

Similarly, the study also found that lead levels found in the remains of sailors buried at a Royal Navy hospital on the island of Antigua between 1773 and 1822 showed a “striking” similarity to the levels found in the remains of the members of the Franklin Expedition.

The scientists caution that the various methods used to measure the two different sets of remains mean that even the results between contemporaries may not be entirely comparable. Still, the variation seen within the Antigua remains, they suggest, is evidence that a number of factors beyond food – including age and occupation – were equally important in determining how much lead sailors were exposed to.

Combining their own results with the results of previous research, the scientists conclude that there is no evidence to support the theory that lead played a pivotal role in the fate of the Franklin Expedition.

The dead may not tell tales, but they can, at least, provide evidence about the lives they lived.