Listening tour hears Inuit call for cross-border polynya management

Depending on your point of view, the expanse of open water at the northern tip of Baffin Bay lies between Danish and Canadian territory, or it lies at the heart of Inuit history and culture.

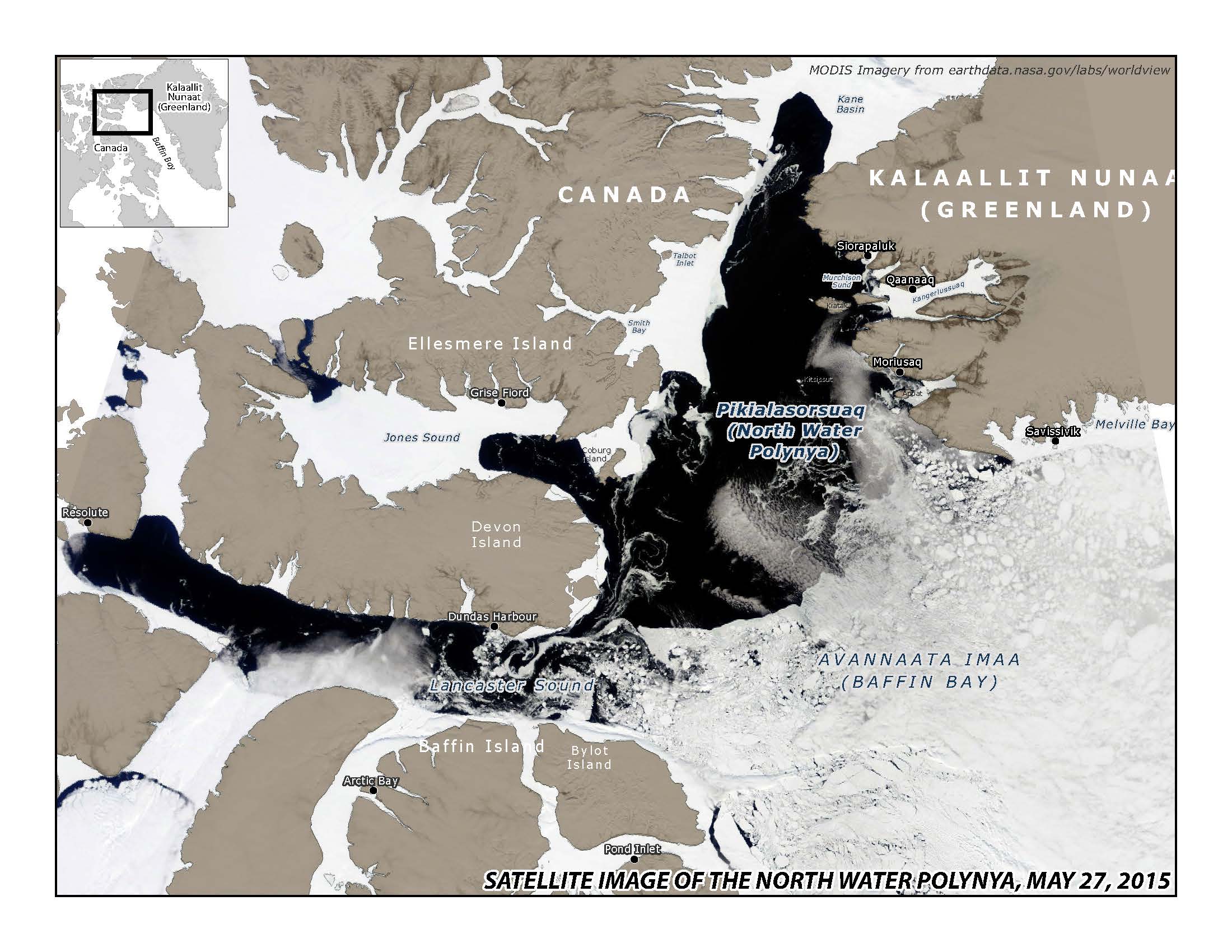

Known in English as the North Water Polynya, and Pikialasorsuaq among Inuit, the 85,000-square-kilometer (roughly 33,000-square-mile) expanse of water is remarkable because it does not freeze over in the winter (it is prevented from doing so by the formation of an ice-bridge further to the north) and, as a result, remains a productive maritime habitat year-round.

Historically, this made it possible to settle the eastern coast of present-day Baffin Island, and far north-eastern Greenland, migration to which was made possible by the ice-bridge). Nowadays, as the area becomes increasingly valuable for shipping, tourism fishing and oil drilling, Inuit who continue to live in the region are concerned they will not have a say in its development.

For this reason, the ICC, an Inuit rights group, convened a meeting in Nuuk, in 2013, to discuss how to ensure continued Inuit influence over Pikialasorsuaq. The outcome of the meeting was a recommendation to create a commission that would travel to communities on both sides to hear people’s opinions.

After being selected this January, the commission’s three members (Okalik Eegeesiak, the head of ICC; Kuupik Kliest, a former Greenlandic premier, and Eva Aariak, a former Nunavut premier) travelled to Nunavut this spring, and Greenland in the autumn to interview residents.

In addition to concerns about increasing commercial use of Pikialasorsuaq, one recurring comment commissions said they heard was the recollection that the open water had once bound the two shores together. Others expressed a desire to be able to cross the ice-bridge freely as their ancestors had.

“People in this region remember a recent past when they could still travel across the polynya’s great ice arch that links Umimmat Nunaat (Ellesmere Island) and Greenland. These communities of the Pikialasorsuaq have long felt connected to the hunting grounds on Ellesmere,” Ms Eegeesiak said in a statement in September at the end of the Greenland tour.

The WWF, a conservancy and one of the financial backers of the commission, presented some of its preliminary findings earlier this week in Nuuk. The full report is due later this year, but statements made by commission members point to a proposal that management of Pikialasorsuaq should be shared by Inuit in both countries.

“Most emphatically, Inuit want to build a caretaking regime for the polynya together as Inuit living, though divided by country, from one sea,” Kleist said.

The commission’s point of view, at least, is clear.