Meet the Russian autocrat who made the U.S. an Arctic nation

On March 29, 1867, literally in the middle of the night, diplomats hammered out a deal that transferred the Russian Empire’s claims in the New World to the United States for $7.2 million.

One-hundred-fifty years later, Alaska knows the name of Secretary of State William H. Seward, the American who negotiated the purchase of Alaska. His name is on a city, a highway, a peninsula and more.

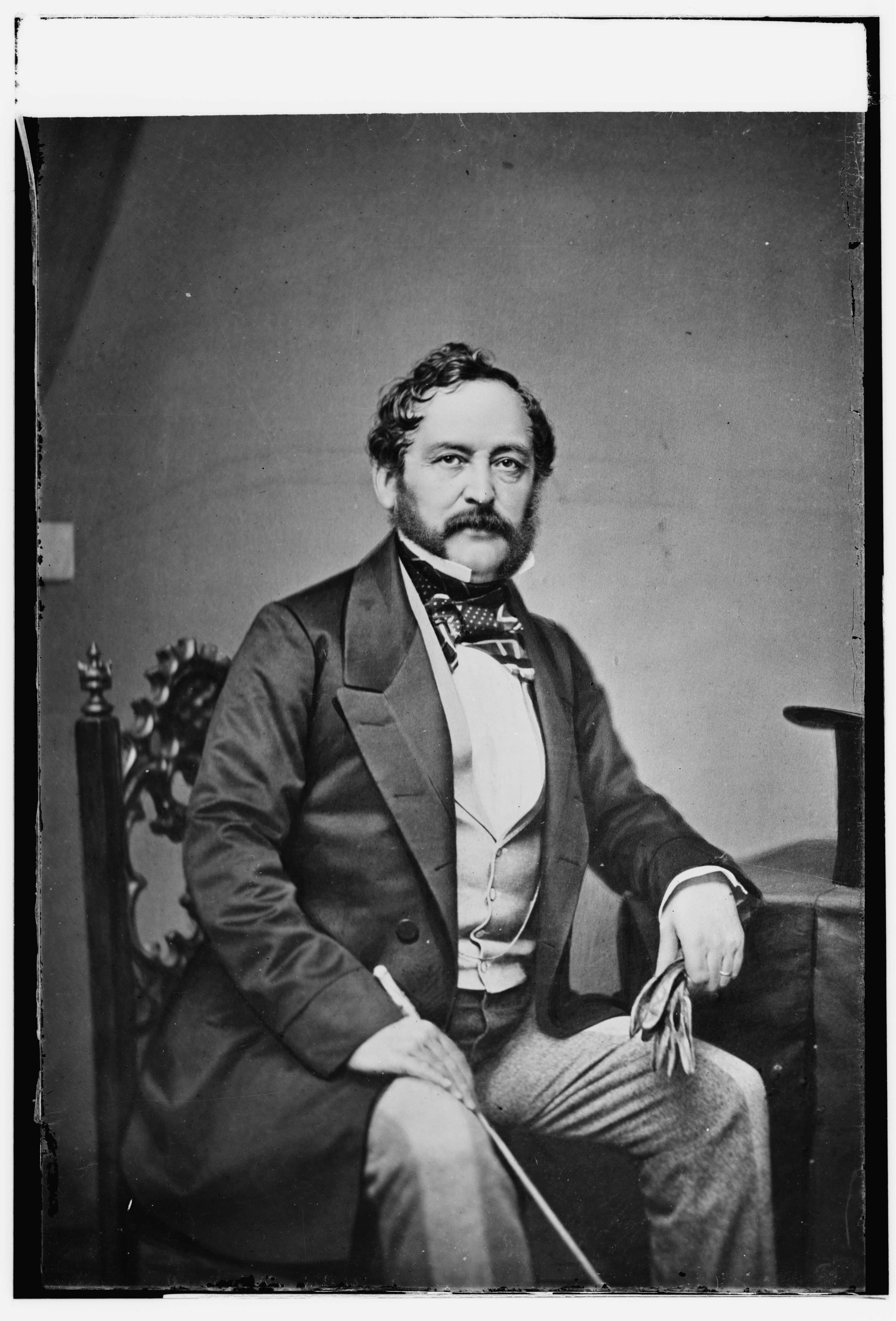

But what of the man on the other side of the table, Alexander II, autocrat and tsar of Russia? Who was he?

It depends on whom you ask. In Finland and Bulgaria he is considered “The Liberator.” In Poland and the Caucasus he is remembered as “The Exterminator.” He ruthlessly suppressed dissent and pursued foreign wars, even while cowering in the face of terrorism at home.

He also brought sweeping reforms to Russia, most famously emancipating the serfs five years before slavery was banned in the United States.

Alaska was just one small page in his career.

The sword of Damocles

From the time of Peter the Great forward, every Russian ruler lived under the threat of violence. In December of 1825 Alexander’s father, Nicholas I, became tsar upon the death of his brother, Alexander I. The Palace Guard, which had been behind every change of government for a century, turned out armed and angry to demand that Nicholas abdicate (and probably face execution).

Little Alexander, age 7, huddled with the royal family in the Winter Palace until troops supporting the new tsar arrived and turned cannons on the “Decembrists.”

Nicholas took the throne as one of the most iron-fisted and suspicious rulers in history.

But he insisted that his heir receive a well-rounded education. Tsarevich Alexander studied everything from physics to military training to woodworking along with the many languages he would be expected to master to rule his own nation and talk with foreign powers.

As he reached the age of majority, Nicholas sent him into the countryside to learn the ways of his enormous territory. Then he sent him abroad to find a wife.

Alexander traveled all the way to England where he was unexpectedly smitten by the clever, vivacious and, in 1838, still single Queen Victoria. She was equally taken by him.

“I really am quite in love with the Grand Duke,” Victoria wrote in her diary, using his formal title. She praised his “fine figure” and “sweet smile.” They danced into the early hours of the morning. “I never enjoyed myself more,” she wrote.

She was ready to accept his proposal. But Nicholas quickly forbade the union. It would not do to have two heads of state in bed with each other, literally, especially since a war between England and Russia was slowly brewing.

“He kissed my hand, and I kissed his cheek,” Victoria wrote of her parting from the Grand Duke. “I felt so sad.”

Alexander came home with 14-year-old Princess Maximiliana-Wilhelmina-Augusta-Sophie of the German duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt. She took the name Maria Alexandrovna and bore five sons and a daughter. She was dull and obedient; Nicholas found her perfect.

A world war

It’s thought that the first suggestion of selling Russian America came up during Nicholas’ reign in discussions with the American ambassador who later became president, James Buchanan. The proposal went nowhere. The United States had no Pacific Coast settlements at the time and Nicholas had a much bigger opportunity at his fingertips.

The Amur River valley, running from the middle of modern Russia to the Pacific, had been vacant for more than a century under the terms of a treaty between Russia and China. In 1854, Nikolay Muravyov, governor of Siberia, sent a fleet down the river and claimed it for the tsar. He was assisted by crews sent from New Archangel, today’s Sitka, who disguised their ships and themselves as Americans to explore the coast in search of the mouth of the river.

Muravyov’s expedition took place at a precarious time. Nicholas had declared war on Turkey and, after initial victories, found himself facing the allied armies of Britain and France for control of the strategic Crimean Peninsula.

The Crimean War took place on several fronts at once. Russia was assaulted in the Black Sea, the Arctic, the Pacific Ocean and, most dangerously, in the Baltic Sea near the undefended capital of St. Petersburg.

But the main action was the siege of Sevastopol on the Crimea. The Allies were disorganized. More would die from disease than in combat. But the Russian defenders were outnumbered and faced the latest heavy arms with the same flintlocks used against Napoleon 40 years earlier. Sevastopol was reduced to rubble.

Nicholas sent his son to report on the action. It fell to the tsarevich to tell the truth to a dictator whom no one dared to contradict: Sevastopol would fall and there was nothing the tsar could do about it.

Nicholas went to his bed and died soon after.

The 1856 Treaty of Paris was highly disadvantageous to Russian interests in the Black Sea. But it left the new tsar with a free hand in the Caucasus Mountains, where a fight with Muslim mountaineers had been going on for decades.

Alexander took his frustration at the defeat in Sevastopol out on the Muslims. Territory was taken with a scorched earth policy at an enormous cost in lives. Civilians were either killed or transported out of the country. Eventually the Muslim leader, Imam Shamil, was captured and brought before the tsar. Much to Shamil’s surprise, the tsar gave him gifts and allowed him to live in style in the Ukraine until his death.

Reforms and bloodshed

In the 1860s, Alexander began the process of widespread reforms. First and foremost was granting freedom to Russia’s 50 million serfs.

“The present order of owning souls cannot remain unchanged,” he told an assembly of nobles. “It is better to abolish serfdom from above than to wait for that time when it starts to abolish itself from below.”

Serfs, like American slaves, could be bought, sold, abused and even killed with relative impunity. But there were some differences between the institutions.

Enslaved blacks had been ripped from their communities and families in the course of being brought to America. Serfs were born and died in a fabric of traditional village life, surrounded by relatives, part of a pattern that went back millennia. “Our backs belong to the masters,” went the saying. “But the land is ours.”

Likewise, the language of liberation was different. In America, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was a few hundred words. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution was less than 50.

In contrast, Alexander’s Emancipation Manifesto, promulgated on Feb. 19, 1861, ran hundreds of pages, a long and convoluted document strewn with onerous conditions. Serfs had to buy the land they thought was theirs at prices above market value. Masters got first pick of the choicest parcels.

Rumors spread that the “real” manifesto granting instant freedom and land had been subverted. Rebellions broke out, drawing a brutal response from the army. The troubles were squelched only when the necessity of spring planting approached.

Other reforms went more smoothly. The military became more democratized and the worst forms of corporal punishment were abolished. Jews were allowed to live where they chose and serve in the government. Court proceedings became open and reported by a relatively liberated press.

But tensions grew in Poland, a subject state to Russia at the time. Landowners there were particularly resistant to losing their serfs. Students rebelled against military service. In 1863 the Poles rose in revolution. Though they achieved notable victories, the outnumbered Polish freedom fighters were eventually crushed. Four-hundred or more were executed. As many as 80,000 were deported.

Another Russian vassal state, the Grand Duchy of Finland, held back from joining the revolution. As a reward, Alexander re-established their representative body, the Diet, and, for the first time in Russian history, accepted the comparatively humble title of constitutional monarch with regard to Finland in 1869.

There were dark clouds at home, as well. His son and heir, Nicholas, died of tuberculosis in 1865. The following year, the tsar was shot at while walking in a St. Petersburg park.

A secret family

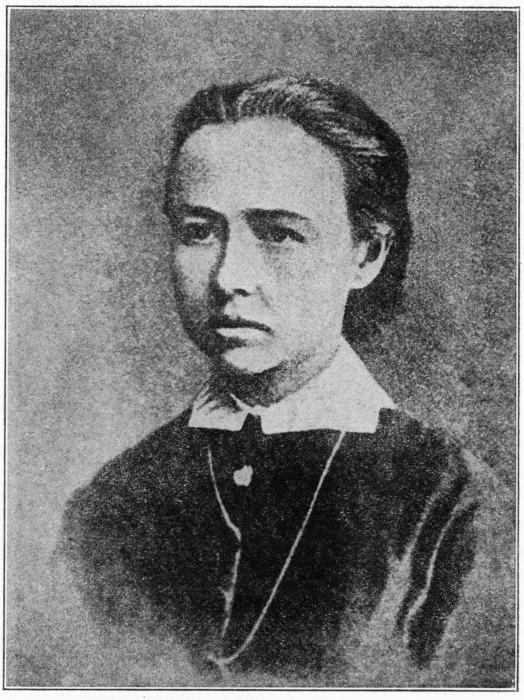

When Alexander was 44, he fell in love with Ekaterina Dolgorukaya, known as “Katya,” age 16. It was no great thing for a young lady of good breeding to spend time in the tsar’s bed, but this girl was different. The two maintained a platonic relationship for some time before making love. Alexander told her, “You are my secret wife. If I am ever free, I will marry you.”

But the palace chatter that swirled around the liaison was more than Ekaterina could stand. The tsar sent her to France and the gossips turned their tongues to other targets.

In 1867, he went to Paris, ostensibly to attend the great World Fair, but also to meet Ekaterina in an anonymous mansion. The joyful holiday turned terrifying when, while riding with French Emperor Napoleon III, a disgruntled Polish exile approached the carriage and fired two shots at close range.

Both bullets missed. (But 14 years later, an assassination attempt by means of the “People’s Will” movement succeeded when a bomb was tossed in his carriage.)

As something of an apology, Napoleon III gifted Alexander with an armored carriage. No apology was sufficient, however, for the humiliation the tsar felt when the French public made a hero of the would-be-assassin, who was sentenced to a slap on the wrist.

Eventually Alexander brought Ekaterina back to St. Petersburg and housed her in the Winter Palace, a few rooms away from where the legitimate Tsarina Maria languished in failing health. On her death he married his “secret wife” who had already born him three children.

Selling the colony

Relations went better with the United States than France. As America broke into its Civil War and the European powers dithered over choosing sides, Alexander unequivocally supported the North. He sent Russian warships to New York and San Francisco in a show of force, just in case France or England harbored any plans to assist the Confederacy. Among those who toured the Russian warships was Mary Todd Lincoln.

The Russian officers were treated to a fabulous state dinner by Secretary of State Seward.

Some say the goodwill visit of the Russian fleets helped smooth the way for the sale of Russian America. The acquisition of the territory had been a key objective of Seward’s for some time, but progress stalled during the Civil War.

When Russia’s ambassador Edouard de Stoeckl appeared at Seward’s house late at night to announce he had received a cable from the tsar approving the sale, the secretary wasted no time in assembling his staff and completing the document before dawn. It was then whisked to President Andrew Johnson for approval and quickly delivered to the U.S. Senate, which quickly consented to the treaty. Seward wasted no time in announcing the deal to the press.

There was no similar announcement from the tsar, however. Russians learned about the sale from accounts picked up from English newspapers. The reaction was widely negative, with strong rebukes coming from press and pulpit. Alexander ordered dissenters to pipe down or risk being charged with sedition. When Admiral Vasily Zavoyko, the hero of the siege of Petropavlovsk and a shareholder in the Russian-American Company, refused to sign documents relinquishing his shares to the government, Alexander exiled him.

Similarly, Stoeckl was denied a promotion, pensioned off and hustled away to France. American historian Hector Chevigny, writing in the 1960s, noted that Russian reference books of that time didn’t even mention his name.

In his 480-page biography of Alexander II, subtitled “The Last Great Tsar,” Russian historian Edvard Radzinsky dedicates less than two pages to the transfer. “The sale of Alaska,” he writes, “is the one act for which Russians have still not forgiven Alexander II.”

Why did he do it? Arguments can be made for the fact that cash was still needed to pay off the debts of the Crimean War, that the colony was not cost effective and that it presented a target to enemies — mainly Britain — who might want to claim it.

The tsar’s brother, Grand Duke Konstantin, was particularly anxious to divest the crown of Russian America. The colony was hopelessly unprofitably and corrupt, he said. The indigenous people were being abused. And, with the opening of the Russian far east and a Pacific port in the new city of Vladivostok, the American outpost was no longer needed.

An official inspection found the colony to be making money, its books in good order. While horrible stories of conflicts between Natives and Russians had been true in the past, the two groups were now largely allied for the common good.

Alaska historian Lydia Black asserts that a mixed creole middle class had developed and was flourishing. Bright young men were sent to study in Moscow and St. Petersburg and returned to the colony with university degrees, becoming the de facto administrators, providing a cultural bridge between their Russian and Native families. Russian Americans enjoyed certain benefits decades before they became standard in the United States — including schools for girls and smallpox vaccinations for infants.

The vulnerability of the colony, however, was a genuine concern. The Crimean War saw fighting just west of the Aleutian chain. A lone Confederate raider, the Shenandoah, wrought havoc with the Yankee whaling fleet in the Bering Sea during the Civil War. The Russian Navy was unable to stop the Yankee poachers or the Shenandoah’s aggression. By letting friendly Americans possess the territory, it might present a buffer between Siberia and British expansion in Canada.

But the Tsar’s motives remain the subject of speculation. He never addressed the matter himself. In some respects he guarded his thoughts carefully, perhaps out of fear of being wrong.

Others observers, however, felt they could read him like a theater poster. In the same year that Alaska was sold, Samuel Clemens — Mark Twain — was part of a group of Americans who visited Alexander at his palace on the Black Sea. The tsar and tsarina welcomed the guests in English and personally showed them the palace. Clemens was struck by the “home-like” décor of the residence as well as by the tsar’s modesty, character and sincere graciousness. “The genuine article,” he said. “If I could have stolen his coat, I would have,” Clemens wrote in “The Innocents Abroad.” “When I meet a man like that I want something to remember him by.”

A bargain then and now

If Russia was selling Alaska today rather than in the 1860s, what would that $7.2 million price tag be worth?

One inflation calculator website puts the number at $101.1 million as of 2016. That’s hardly chump change, but how much is it really?

• Less than a gorgeous California mansion that Town and Country magazine lists at $250 million.

• Less than what Alaska has spent on studies and contracts for either the proposed Knik Arm bridge, the Susitna dam or the trans-Alaska oil pipeline.

• Less than what it cost to make either “Captain America” or “Batman vs. Superman” films released last year. Both of those were $250 million projects.

• About a third of the $325 million contract that Major League Baseball’s highest-paid player, Giancarlo Stanton, signed in 2015.

While the Alaska sale happened quickly, U.S. politicians in the 1860s backed away from the idea of buying British Columbia for $15 million, or $2 billion for all of Canada. Oh, Canada.

Former Alaska Dispatch News arts reporter and editor Mike Dunham is the author of “The Man Who Sold Alaska: Tsar Alexander II of Russia” and “The Man Who Bought Alaska: William H. Seward,” both published by Todd Communications.