Meet three women who are racing to defuse a climate-change bomb in the Arctic

Arctic methane is an important climate threat — but a poorly understood one. These researchers are trying to change that.

Banking hard over the whitecaps off the west coast of Norway, the jetliner flying Dominika Pasternak and her fellow scientists descends so sharply that it seems for a moment as if the crew is about to ditch them all in the drink.

But the pilot, an unflappable veteran of Britain’s Royal Air Force, conveys a done-this-a-thousand-times confidence as the aircraft levels off at nerve-shredding 50 feet above the North Sea.

“Three, two, one,” he advises over the intercom. “Now!”

And so begins the work of this giant airborne laboratory — a four-engine, 112-seat passenger plane stripped out and refitted with sensors that suck in air samples for analysis in real time.

Although they squint through the cabin windows as the plane makes its pass, Pasternak, 23, and her colleagues are chasing a quarry they will never actually see: methane, an invisible gas that poses a growing risk to the Earth’s climate.

Calls to cut emissions frequently focus on a more familiar greenhouse gas — the carbon dioxide produced by burning fossil fuels.

But methane, another carbon-based compound, is emerging as a wild card in the climate-change equation. If CO2 has a warming effect akin to wrapping the planet in a sheet, the less-understood methane is more like a wool blanket.

Emitted from sources such as thawing permafrost, tropical wetlands, livestock, landfills and the spidery exoskeleton of oil and gas infrastructure girdling the planet, methane has been responsible for about a quarter of manmade global warming thus far, some models calculate.

[Thawing permafrost could release a long-lasting greenhouse gas at ‘surprising’ rates, says study]

For more than a decade, scientists have been documenting a mysterious rise in levels of methane in the atmosphere. And it’s getting worse: Earlier this year, data from the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration showed that the rate of the increase surged by 50 percent in the 2013-2018 period compared with the preceding five years.

But the very urgency of the methane threat is also, paradoxically, what gives some scientists hope. Because methane is acting like a foot on the accelerator for climate change, then rapidly reducing the amount leaking from oil and gas facilities could, at least in theory, ease the pressure on the environment. That could buy time to confront the much bigger challenge of cutting emissions of C02.

In the United States, environmentalists have sought to bring methane emissions down by pushing the growing fracking industry to take more stringent measures against leaks of the gas. But earlier this year, the Trump administration proposed rolling back Obama-era regulations to curb methane emissions, saying the move would save companies money and remove red tape.

As the clock ticks, a network of researchers the world over is racing to find out why global methane levels are increasing so fast — and what can be done to stem the flow.

[Spring rains boost permafrost methane emissions, study finds]

Here in the Arctic Circle, which is warming three times faster than the global average, Reuters accompanied three women in their twenties as they hunted for clues. Working separately but with the same goal, these researchers have staked their claim on a place where some of the most dramatic climate changes are starkly visible, and the biggest dangers may await.

In their painstaking, sometimes solitary work, the three young scientists wrestle with the intellectual challenges posed by the methane riddle. But for all three women, their work in the Arctic connects them to something deeper than science: a return to childhood joys of the natural world, and a powerful sense of purpose.

Pasternak, wearing a white T-shirt bearing the words “Climate: The Fight of Our Lives” and a stylised image of the Earth engulfed in flames, is clear-eyed about the stakes.

“I think it’s terrifying how much we are changing our planet, and how little is really done to counteract it,” she says. “We are guessing, but the more measurements we actually have, the better we can understand what’s going on.”

As the jet races over the waves, Pasternak’s gaze flickers between the cabin window and her laptop — displaying a rolling graph of data recorded by the plane’s instruments.

The clipped voice of the pilot, laconic as ever, crackles over her headset, “I can see rigs on the left.”

Pasternak, a Polish PhD student in atmospheric chemistry at Britain’s University of York, focuses on the target: a cluster of oil rigs rising from the sea like fortresses, their squat legs supporting imposing superstructures of derricks, helipads and cranes.

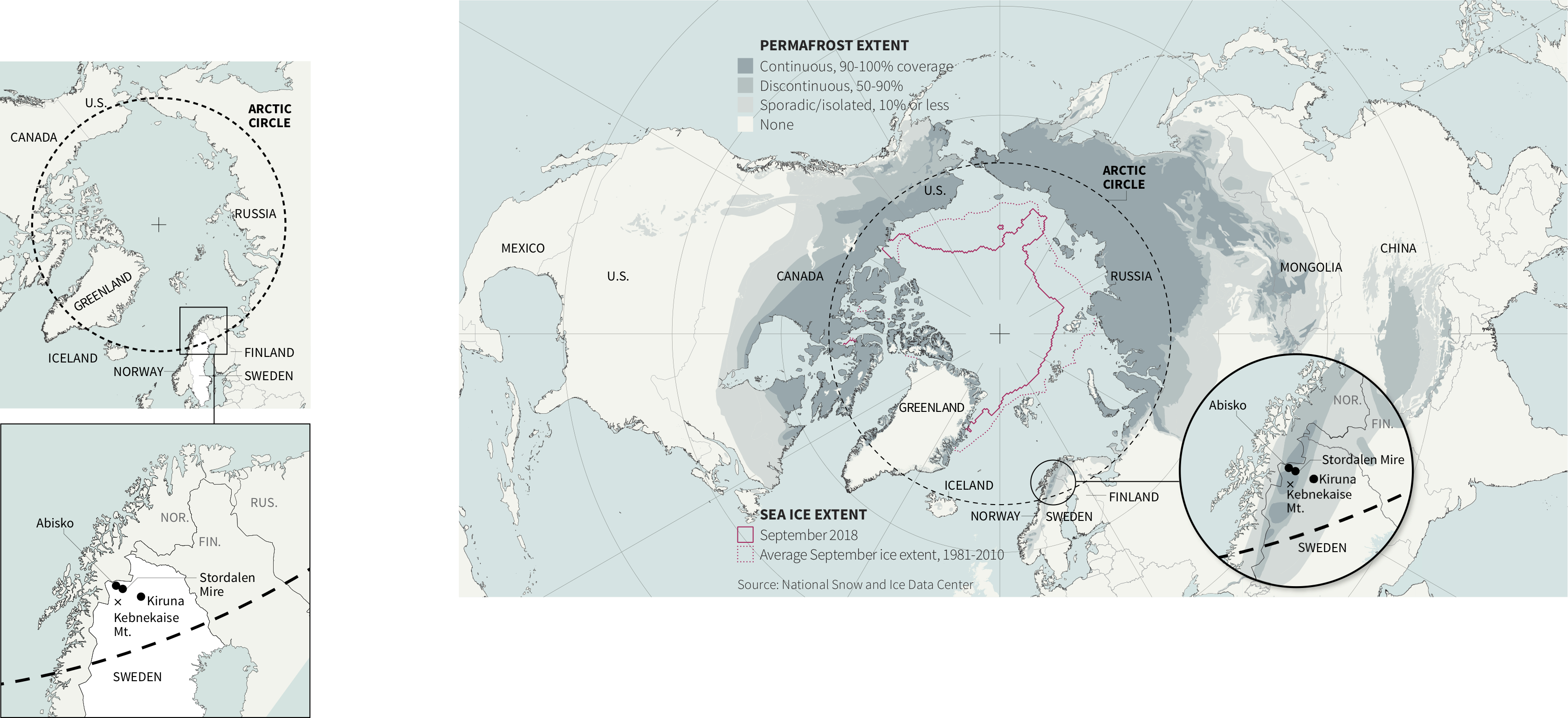

Operated by the Natural Environment Research Council, a British government science funding agency, the flight is one of a series of sorties that Pasternak and colleagues from several universities conducted in late July and early August from Kiruna, an iron mining town in the Lapland region of northern Sweden.

The plane moves in a deliberate path, passing back and forth at different altitudes to build up a profile of the atmosphere downwind of the rigs below. Securely strapped in against the G-force at low altitudes, Pasternak and the other researchers confer over headsets and monitor the readings scrolling across their screens for any sign of a spike in methane levels. Their concentration is palpable, chatter kept to a minimum in the rigours of low-level flight.

But after hours of methodically surveying the rigs, there is no sign of the kind of methane cloud they detected billowing from another platform the day before.

Frustratingly for Pasternak, the aircraft also narrowly missed a giant supertanker, its bright red hull bulging with domes used to store liquefied natural gas.

“They unfortunately got out of our range now, which is a shame,” says Pasternak, who had hoped to take a methane reading near the vessel. “They are hard to catch because they are very specialised ships.”

For Pasternak, the flight is more than a research trip: It’s the realisation of a childhood dream. Growing up on a hillside outside the industrial city of Krakow, she would awake to see a layer of pollution settled over the city like a shroud, then brave the smog to go to school in the valley below. Escaping to the pristine Bieszczady Mountains for horse-riding summer camps or to the old-growth Białowieża Forest, Pasternak promised herself she would find a way to protect the environment by pursuing a career in science.

As the plane makes its way back to its temporary base in a hangar in Kiruna, she is sober about the uncertainties.

“Not many people paid attention to methane until quite recently,” she says. “We don’t know enough about it to be able to tell how dangerous it is, but we suspect it’s very dangerous.”

Although the Italian inventor Alessandro Volta is better known for designing an electric battery, he is also credited as the first scientist to identify methane, or CH4. Collecting gas seeping from the marshes on Lake Maggiore in 1776, he later showed the gas could be ignited with a spark.

More recently, scientists have quantified methane’s potency as a greenhouse gas. Although it is much less prevalent in the atmosphere than CO2, the scientists found, it can generate more than 80 times more warming – molecule for molecule – than C02 in the 20 years it takes to dissipate.

Today, there is broad agreement on the trend showing a surge in methane levels, but there is far less consensus on why it’s happening. Although oil and gas facilities are the leading industrial source of methane, scientists believe that growing amounts of the gas seeping from tropical wetlands in Africa and South America could be the biggest single driver of the current methane surge.

As the burning of fossil fuels pushes global temperatures higher, methane-spewing microbes in fast-warming soils near the equator are going into overdrive, causing the wetlands to emit more of the gas. These emissions in turn feed more warming, in a vicious circle. Climate scientists call such loops “positive feedbacks” — although their effects are anything but.

In the long term, the Arctic could be just as dangerous. As the permafrost thaws, dormant microbes find themselves immersed in the perfect warm, wet conditions to begin producing methane in climate-altering quantities, just like their tropical cousins.

“The methane is then going to mix around the world multiple times,” says Ruth Varner, director of the Earth Systems Research Center at the University of New Hampshire, who runs a long-term methane study. “What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic.”

In winter darkness, meters of snow cover Stordalen Mire, a spongy patch of Swedish peatland about an hour’s drive from Kiruna Airport. The ice on a nearby lake is so thick you can confidently scoot across it in a snowmobile.

But in summer, the snowpack recedes to slithers on distant peaks, wispy heads of cottongrass peek through the soil, and the sun rarely sets. On such a day, Kathryn Bennett, 22, can be found pulling the oars of a rowboat.

On the shore, bogs lie in wait for anyone who strays too casually from a precarious series of walkways made from planks.

“I have fallen in clear to the waist,” says Bennett, a postgraduate student in earth sciences from Medway, Massachusetts, and a member of the methane research program at the University of New Hampshire. Although she laughs, her expression suggests the dunking was amusing only in retrospect.

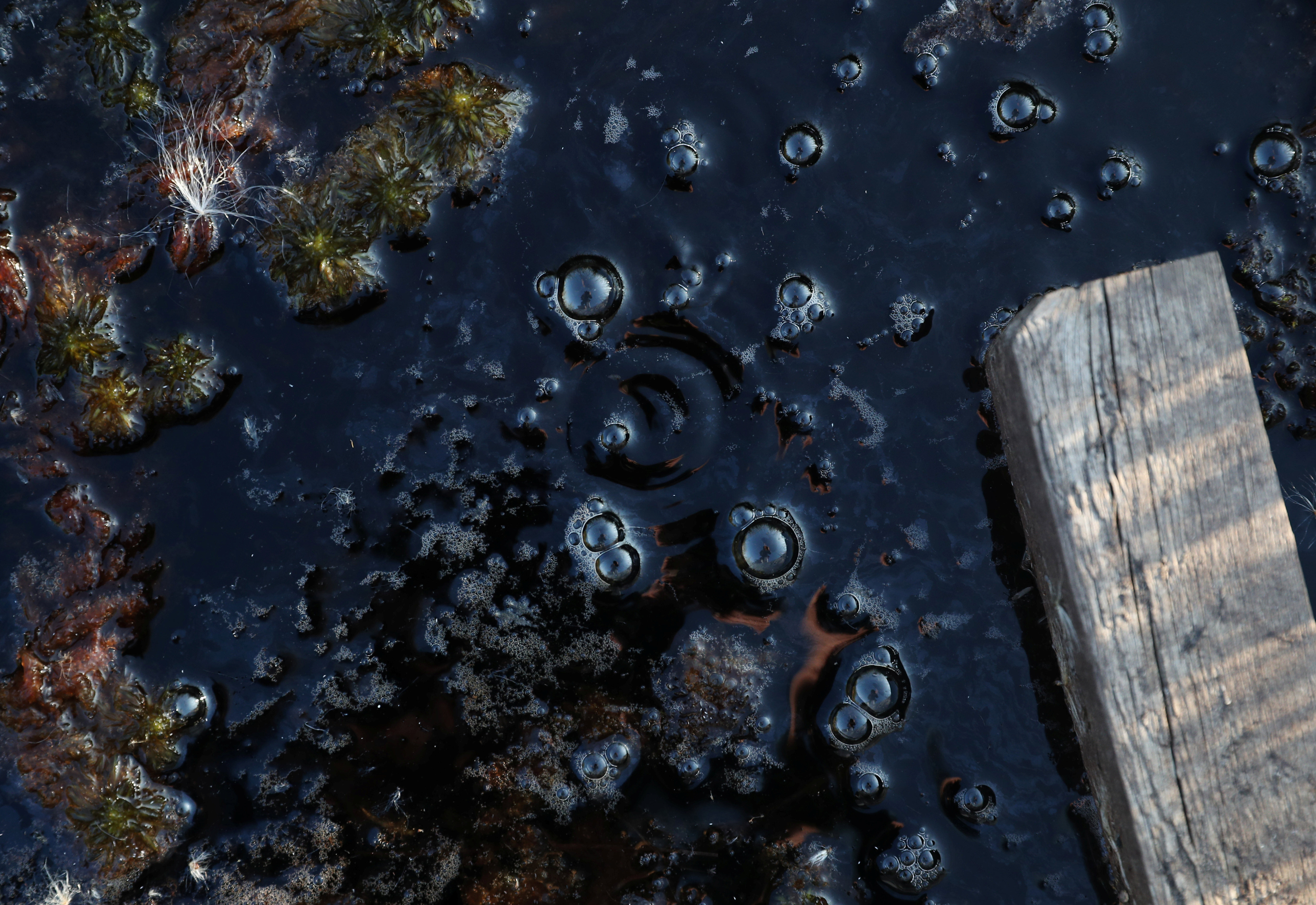

If Pasternak is serving in the air wing of the methane army, then Bennett is one of the grunts — picking her way across the bogland day after day and kneeling at the water’s muddy edge, where tiny bubbles of methane burp periodically from a surface with a texture like used coffee grounds. Syringe in hand, she extracts samples of gas accumulating in floating, foam-reinforced funnels, which she will later test to determine how much methane they contain.

A few locals pass by in the distance picking cloudberries, and a dragonfly zips in jagged loops over the brackish water. Bennett keeps half an eye out for antlers, having been startled and delighted to see a couple of moose cooling off in the marsh two days before.

“It’s so wild out here, you never know what you’re going to run into,” Bennett says, wearing black waterproofs against the chill air.

Even to a first-time visitor, something about the landscape at Stordalen doesn’t look right. The walkways have subsided in places as the ground has given way, meaning Bennett’s footfalls sometimes splash in the stagnant water — which she says has crept a little higher than during her fieldwork the previous summer.

The slumping is a sign that the underlying layer of permafrost that once kept the ground rock solid has started to thaw. On drier patches of ground, long, narrow cracks have appeared. In the marshland, new ponds have formed.

Researchers in other parts of the Arctic are witnessing similar changes. A team from the University of Alaska Fairbanks reported earlier this year how amazed they had been to find millennia-old permafrost in Canada thawing 70 years earlier than models had predicted, leaving depressions resembling those at Stordalen.

[Strong methane emissions in Canada’s Arctic linked to sub-permafrost methane banks]

“If this continues to happen, we can’t turn it off,” Bennett says, her concern suddenly audible in her voice as she pauses by one of the bogs. “You can’t just flip a switch and switch to an electric car or solar panels. You can’t just stop the permafrost from thawing, because it’s already begun, which we see very clearly in places like this.

“Then it becomes: ‘Well, what can we do?’ As scientists, what we can do is just try and understand this system and make better predictions about how it’s going to change in the future.”

Bennett traces her love for the outdoors to a childhood growing up camping and catching frogs. Although she draws some comfort from the contribution she’s making to understanding methane’s role in climate change, she’s also keenly aware that even by flying to Sweden from the United States, she’s adding to the emissions that cause it.

“Seeing really dramatic changes like this makes me think a lot harder about the individual choices that I make and think about how can we get other people to care,” she says, nearing the end of a nine-week stint in Lapland. “It hurts me to think that I fly all the way over here to study this, but then it’s so important to tell people this story, to understand, and tell people about what’s happening here.”

Climate scientists say the world must rapidly wean itself off its dependence on fossil fuels to stand a chance of averting the worst effects of rising temperatures. In the United States, oil companies argue that they can support a wider transition to renewable energy by providing natural gas from the fracking industry as a “bridging” fuel. Gas has already displaced much of the country’s coal-fired power generation, which produced much more C02.

But studies suggest that about 3.5 percent of natural gas escapes as methane during production, storage and transport — exerting significant short-term warming.

Alex Turner studies methane as a postdoctoral fellow in atmospheric chemistry at the University of California, Berkeley. Because methane is such a fast-acting, relatively short-lived warming agent, cutting leaks of the gas would have a quick impact on the climate system, Turner argues. That might help prevent runaway climate change from kicking in before the world has managed to control C02 emissions — by far the biggest driver of long-term global warming.

“Of the greenhouse gases, methane is a really big lever on near-term climate change,” Turner says. “Large fractions of emissions tend to come from a small number of sources, and if you can find those sources that emit a lot of methane, you might be able to make a huge dent in the total emissions.”

In 2012, a network of governments, scientific institutes, businesses and civil society groups founded the Climate and Clean Air Coalition to curb emissions of powerful, short-lived pollutants such as methane. Since then, the U.N.-backed network has funded research around the world, including Pasternak’s flight this summer.

Some big oil companies say they’re taking the problem seriously. Under pressure from activists and investors to show it is doing more to tackle emissions, British oil major BP Plc just announced plans to use cameras, drones and robots to try to detect and prevent methane leaks at facilities around the world, for example.

“We are wanting to do continuous measurements and monitoring in all our future big projects,” says Gordon Birrell, a chief operating officer at BP.

But some smaller drilling companies say they lack the resources that the majors can bring to bear on the methane problem.

“There are certainly countries and firms that are very resistant, but the issue has started to gain real momentum, almost from a standing start just a few years ago,” says David McCabe, a senior scientist at the Clean Air Task Force, a U.S. advocacy group. “It’s a case of trying to speed that up.”

Clad in khaki shirts and shorts like an old-school explorer, Nina Lindstrom Friggens sets off through the dwarf willow shrubs clinging to a lakeside near the northern Swedish village of Abisko. Her mission: to understand how the hidden lives of trees will influence the future of the climate.

Kneeling at the base of a mountain birch, a stunted tree adapted to survive the Arctic‘s incessant cold and wind, she flicks open a saw-toothed pocketknife and begins to dig.

Delicately, she lifts a lattice of roots between forefinger and thumb and uses the knife tip to point out minute white sheaths that have formed over the finest filaments: fungi that live symbiotically with trees under the soil.

The 26-year-old Danish-British ecologist has always been fascinated by Arctic landscapes, in part thanks to her childhood love of Philip Pullman novels set in frozen Norse fantasy worlds. Unlike Pasternak and Bennett, who are methane hunters to the core, Lindstrom Friggens works on a broader carbon canvas, working to piece together the interplay between soil, ice and vegetation that will determine how quickly greenhouse gases seep from these northern lands.

The fungi she studies form a biological version of the internet — what scientists have nicknamed a “wood-wide-web” — that allows trees to swap chemical signals and nutrients. As the Arctic has warmed, it has also increasingly turned from white to green, as saplings gain a foothold in the depressions left as the permafrost thaws.

That’s good news in terms of methane, because tree-covered land is likely to emit less of the gas, says Lindstrom Friggens, a PhD student in plant-soil ecology at Scotland’s University of Stirling. But there’s a big catch: The expanding root networks help to rapidly decompose ancient subsoil stores of carbon into vast quantities of C02, setting new feedback loops in train.

How quickly thawing permafrost could push the Arctic‘s production of methane into overdrive is still a subject of speculation. But the impact of warming on the region was made vividly clear earlier this month, when scientists jolted Swedes by announcing that the south peak of Kebnekaise, the large mountain not far from where all three young scientists were conducting their research, had been dethroned as the country’s highest peak.

The glacier on the summit, previously considered a permanent, majestic fixture of Scandinavia’s natural heritage by generations of Swedish schoolchildren, melted so quickly that it is now lower than the mountain’s ice-free northern peak.

Reflecting on the prospect of far greater climate impacts, Lindstrom Friggens finds solace in nature’s ability to endure.

“I quite like that it’s bleak and it’s rough; there’s a beauty in that somewhere – that struggle to survive in an environment which is throwing everything at you all the time,” she says.

A seagull glides low over the lake, and the immense landscape of water, sky and rock feels almost unfathomably old. A raw life force seems to hum inaudibly in the Arctic silence as Lindstrom Friggens reaches a path leading back to the research station that is her temporary home, where she will watch the endless summer days start to shorten.

“There’s so much life, yet it’s so harsh to survive here,” she says. “But it perseveres.”