Miners upbeat ahead of Toronto rite of spring

The mining industry heads to Toronto next week for the annual PDAC gathering with renewed confidence.

One of the sure signs of spring for miners is the annual PDAC convention. Held every year since 1932, PDAC (short for Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada) is the biggest event of the year for the sector, drawing participation last year from 130 countries.

The mood at this year’s gathering, which begins on Sunday, will be more upbeat than in recent years. After falling to historic lows just a few years ago, commodity prices are on the rise. Analysts across the board suggest this is a trend that is likely to keep up, without danger in the near term of the unsustainable expectations that preceded the crash.

“After hitting low points, prices for many commodities have been slowly recovering. Unlike previous cycles, mining companies appear to have learned from the lessons of the past,” said Philip Hopwood, of Deloitte, a consultancy, in connection with the presentation of its annual review of the industry.

[Is Arctic mining poised to make a comeback?]

As with other industries, mining-related gatherings abound. Individual jurisdictions, in particular, seem to be keen to organize pep-talks that can convince investors to pump money into their underground. For hard-to-reach places such as territories in the Arctic, this often requires taking the show on the road and pitching their message to a select audience; showing up at PDAC, whose attendance measures in the tens of thousands, brings their messages to the mining masses.

By now, the Arctic’s geologic potential is well-established, so investors will be listening more closely for other signs that the region’s jurisdictions are an attractive place to do business. Comparisons across borders are difficult, but the 2018 World Risk Report, published by the Mining Journal, a trade magazine, underscores that such differences can play a huge role.

Greenland, for example, is described as rich in various types of elements and surrounded by natural deepwater ports. “What’s not to like?” the authors ask. Quite a bit, apparently: the survey gives a rating of ‘CCC,’ fourth-lowest on the magazine’s ten-point scale, in large part because of a lack of infrastructure.

The industry’s unfamiliarity with the country’s mining regulations also draws down the ranking, despite the survey’s assessment they that they appear well-suited for the country’s goal of getting five to 10 major mining operations on-line in the coming decade. Still, those who do have experience with the rules warn that they look better on paper than in practice, in contrast the most other jurisdictions.

[Arctic nickel — not Arctic oil — could soon power the world’s cars]

Finland, the other country this year’s issue looked at, is also a jurisdiction with “major geological potential.” Yet, it gets a ‘AA’ rating, the second highest ranking possible, for its “supportive mining code and reliable infrastructure all over the country,” leading to the conclusion that Finland should be high on any explorer’s list.

The Annual Survey of Mining Companies, published by Fraser, a Canadian think-tank, each year around the time of PDAC came to similar conclusions this year, ranking Finland as the best place overall for mining. Greenland finishes in the middle of the field of 91 jurisdictions, second-to-last among Arctic territories.

Detractors of publications like these argue that as measures of “attractiveness” and “perception” they are better used for describing where jurisdictions are coming from, not where they are headed.

A better measure, according to mining authorities, is the price of commodities; because the Arctic’s geologic potential is already proven, higher prices will go a long way towards reigniting interest in stalled projects. Where that falls short, they will be able to point to an increasing number of success stories. The past year saw several high-profile projects come on-line, including Gahcho Kué, a diamond mine in the Northwest Territories that is the largest such operation in more than a decade.

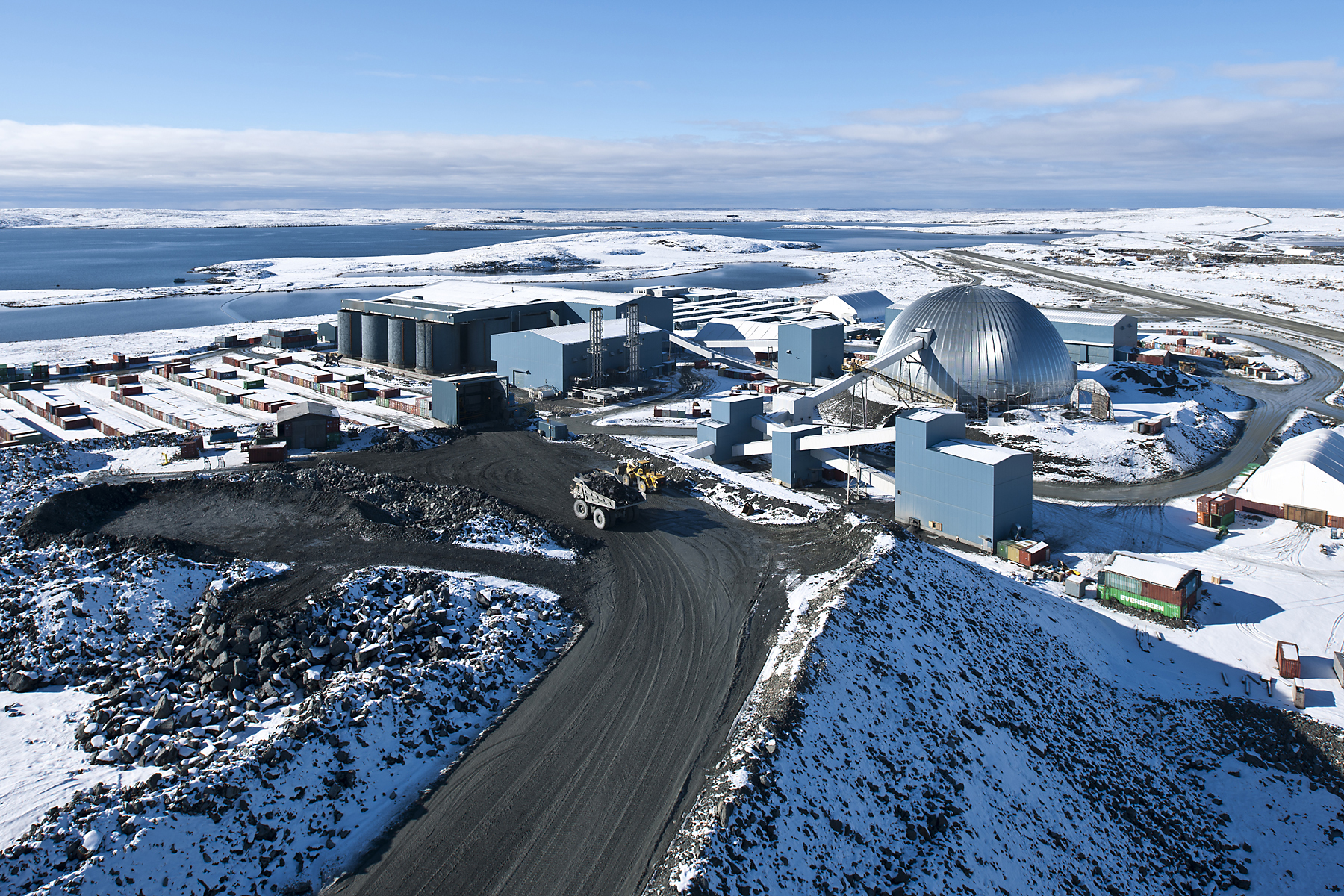

Agnico Eagle, a Canadian gold mining company, has also announced it will make major investments to expand its operations in Nunavut and Lapland that will greatly expand the longevity of both. Baffinland, which also operates in Nunavut, is pushing for an expansion of its Mary River iron-ore mine that its bosses say will keep it running for 150 years.

Likewise, Greenland, made its long-awaited return to the ranks of active mining jurisdictions with the opening of the Aappaluttoq Ruby mine. A second mine was expected to begin operation, but has been delayed until this year. The hiring process for that operation has already begun.

Hope, as ever, springs eternal.