More people are visiting northern Sweden. Too many are leaving something other than footprints behind

After efforts to get visitors to take their waste with them, regional officials in Norrbotten are now deliberating whether to make it easier for them to leave it behind.

As northern Sweden has become increasingly popular among travellers, the Norrbotten region has begun considering whether it should set up portable toilets along some of the most popular hiking paths, as well as at the top of the country’s highest peak.

Since the turn of the century, tourism in Swedish Lapland — measured by a variety of parameters, including number of guests, turnover and those employed in the industry —has doubled.

Those visiting Norrbotten are attracted by the region’s unspoiled wilderness. And while the portable toilets would put a chink in that image, businesses and Sámi reindeer herders feel that giving people an alternative to answering the call of nature in nature is necessary to keep matters from getting worse.

In general, tourism growth is welcome in Norrbotten, and the industry has been shown to complement other economic activities. Reindeer herders, though, are concerned that, when hikers set up camp near their villages, they use their herding grounds to relieve themselves.

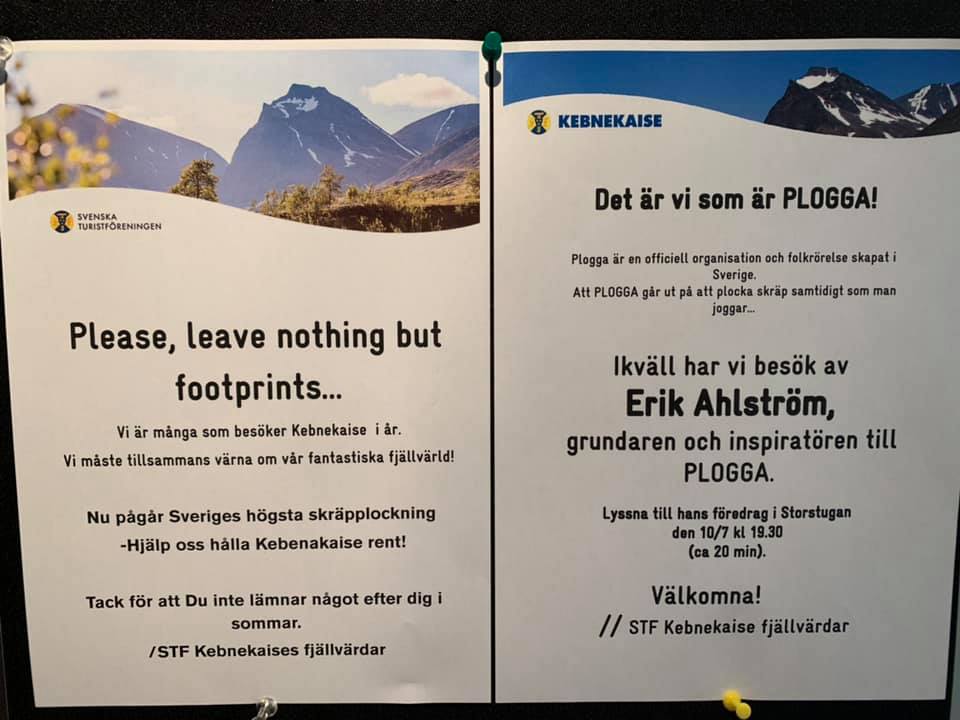

Previous efforts to deal with the increasing amount of waste in the Norrbotten wilderness have centered on encouraging and even rewarding visitors to pack out their refuse, but they have had little effect.

Kebnekaise, measuring nearly 7,000 feet (about 2,100m), is scaled by an estimated 10,000 people each year, most of them during the summer months. Reaching the top of the mountain is relatively easy, making it a popular destination for hikers. As a result, the hostel at the mountain’s base is typically sold out during the summer, and the two paths to the summit are frequently crowded.

“There are a lot of people who want to climb Kebnekaise. We could find ourselves having to fly in a porta-john like you would see at big events,” Ivar Palo, of the Norrbotten Länsstyrelsen, the regional authority, told SVT, a broadcaster.