NASA research flight around the world probes for Arctic pollution

Air pollution can be obvious when it is concentrated around cities and industrial centers. But what about the big parts of the atmosphere that are far from freeways or factories?

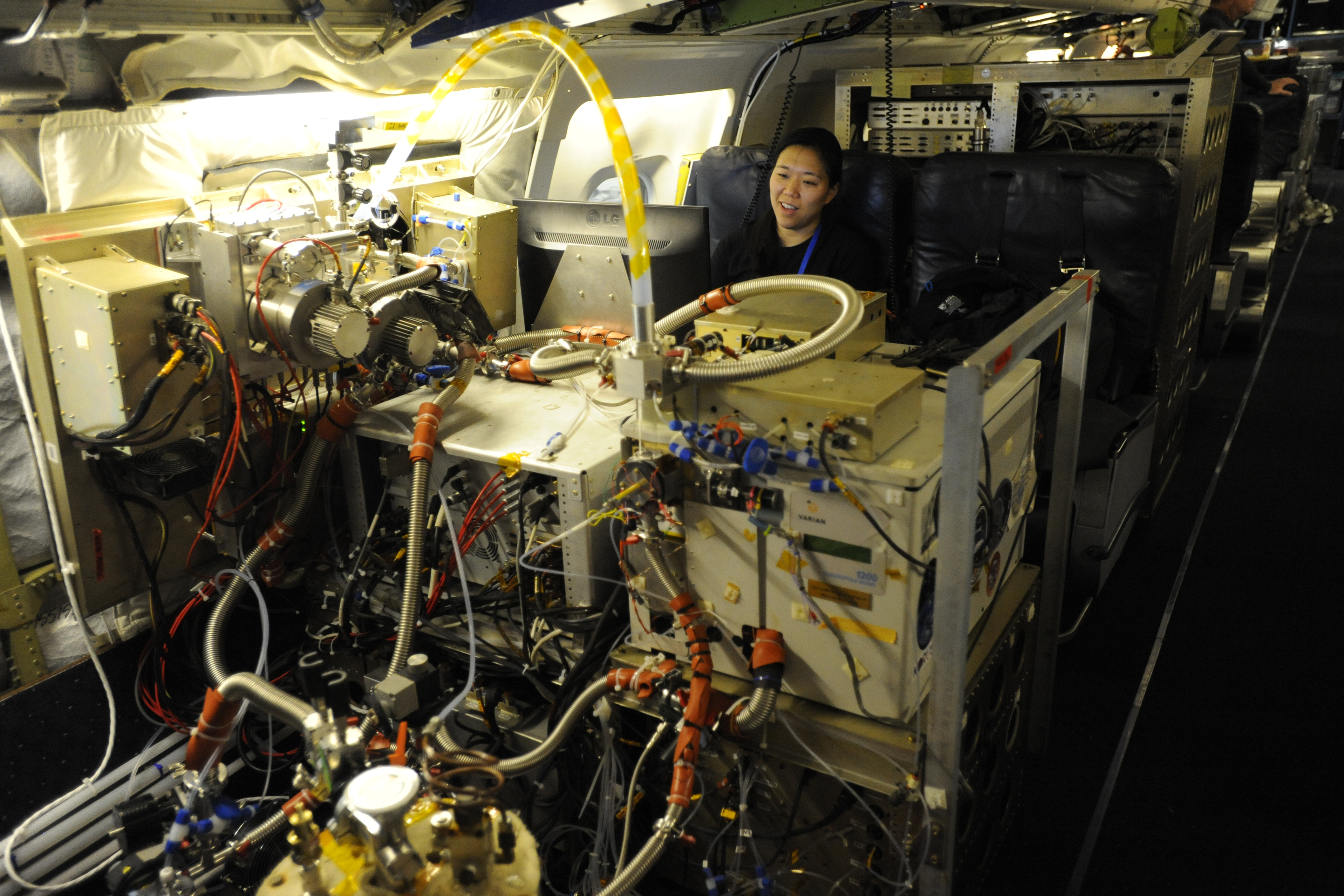

Finding the answer to that question is the purpose of a NASA project that is sending an equipment-laden and scientist-packed DC-8 passenger jet around the world, over the middle of the Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic oceans, with brief stops in Anchorage and other locations.

The Atmospheric Tomography Mission — ATom for short — is taking samples from deep in the Southern Hemisphere to the Arctic to gather more information about what gases and particles exist in the air far from most human habitation — and how the pollution got there.

The focus is on short-lived greenhouse gases like ozone and methane and aerosols like black carbon, all of which contribute to climate change. In all, about 200 types of gases and particles are being measured. A key goal is to understand how the chemistry of the remote atmosphere changes, sometimes in a matter of seconds, said Michael Prather of the University of California at Irvine, the project’s deputy principal investigator.

The air above the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, which are the “bulk processors” of the atmosphere, is considered to be some of the cleanest in the world, and that is why it is being examined for chemical patterns and pollutants emitted from faraway sources, Prather said Tuesday during a tour of the research plane as it was parked in the FedEx hangar in Anchorage.

“It’s affected, but distantly. We do find out how it’s distantly affected, which is the hard part,” Prather said. ”We’re trying to get a typical sample of how spotty it is, how much schmutz you see at times, how clean it is. … We don’t really have good statistics on how much pollution reaches this area.”

The ATom project started in July and sampled atmosphere in the Southern Hemisphere’s winter and the Northern Hemisphere’s summer. This tour, the second in a series that is expected to be conducted over a three-year span, is taking samples in opposite seasons; the goal is to get a variety of seasonal samples.

Each tour takes about 3 1/2 weeks to complete, and the tours are staggered over a period expected to stretch three years. There are brief stops, for periods ranging from one day to four. Anchorage is a two-day stop; the team arrived Sunday night and is scheduled to leave Wednesday morning. The longest break is a four-day stopover at Christchurch, New Zealand, where the National Science Foundation has a station and where much of the resupply work can be done.

When it is not being used for ATom, the DC-8 aircraft has other uses for NASA. It is reconfigured and re-equipped for other missions, notably Operation IceBridge, a six-year program that is surveying Earth’s polar ice.

Passenger accommodations are spare. There is very limited space for personal luggage — creating a packing challenge for scientists who are veering from tropical sites like Fiji to Greenland and back again — and the galley area holds not much more than a microwave oven and some coffee supplies.

Travel conditions are also taxing. Flights last up to 11 hours and scientists generally have to come aboard three hours ahead of departure to prepare their equipment, then stay for an hour afterward to shut things down and debrief.

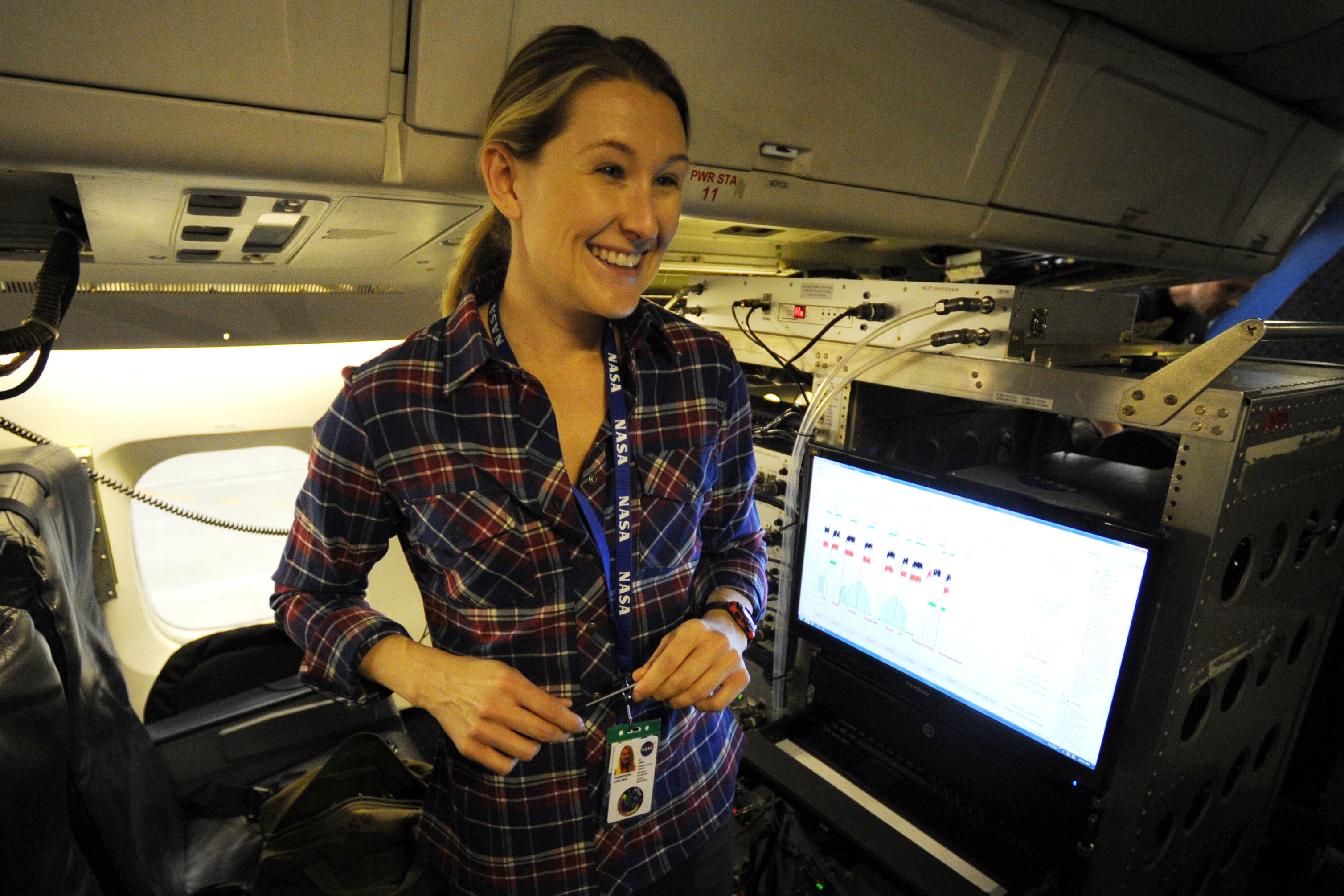

Scientists said they spend much of their flight time watching the screens and monitors of their instruments, not the scenery out the window.

But sometimes that scenery is striking, said team member Chelsea Thompson of the University of Colorado. Amid her work measuring nitrogen oxides and ozone, she was able to photograph and video an unusual sight in January in the Arctic Ocean waters off Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) — lots of open water amid thin and fractured pack ice.

“It was broken and frizzled. It’s not thick. It was mostly open water,” she said. That was a big contrast from the scene in 2009, when she was in the area working on her Ph.D. and people could drive trucks on the sea ice, she said.

Bigger expanses of open water in the Arctic that used to have more sea ice are known to be emitting more water vapor into the atmosphere. But the trend is not something that can be detected in a single flight, said Glenn Diskin of NASA’s Langley Research Center, who is using laser beams to measure water vapor.

Knowledge about water vapor in the atmosphere is important for understanding climate, Diskin said. “Water vapor is the most important greenhouse gas. But it’s not something that we control directly,” he said. Rather, human-sourced carbon, like carbon dioxide from combustion, creates warming conditions that put more water vapor into the atmosphere, feeding into a warming cycle, he said.

Another sight out the window in the previous tour left a deep impression.

When flying off Africa, they saw a big “pale, ugly sort of brown” cloud of combined sand from Sahara dust storms and soot from biomass burning — all sources that were about 600 miles away, said ATom team member Jim Elkins, a Boulder, Colorado-based scientist for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“It’s kind of like when the astronauts go up to look at the Earth, they’re struck by how fragile it is,” Elkins said. “My perspective was, it really hits home that air quality and particles in the atmosphere are really devastating to the quality of our atmosphere, which we all breathe.”