Neiman Marcus agrees to settle in landmark Indigenous property rights case

But attorneys say more legal action is expected to protect those rights.

The retail giant Neiman Marcus and some associated companies have agreed to settle a year-old lawsuit over actions that an Alaska Native organization considers illegal appropriation of a Tlingit design, in a case that could have far-reaching implications for Indigenous intellectual property rights.

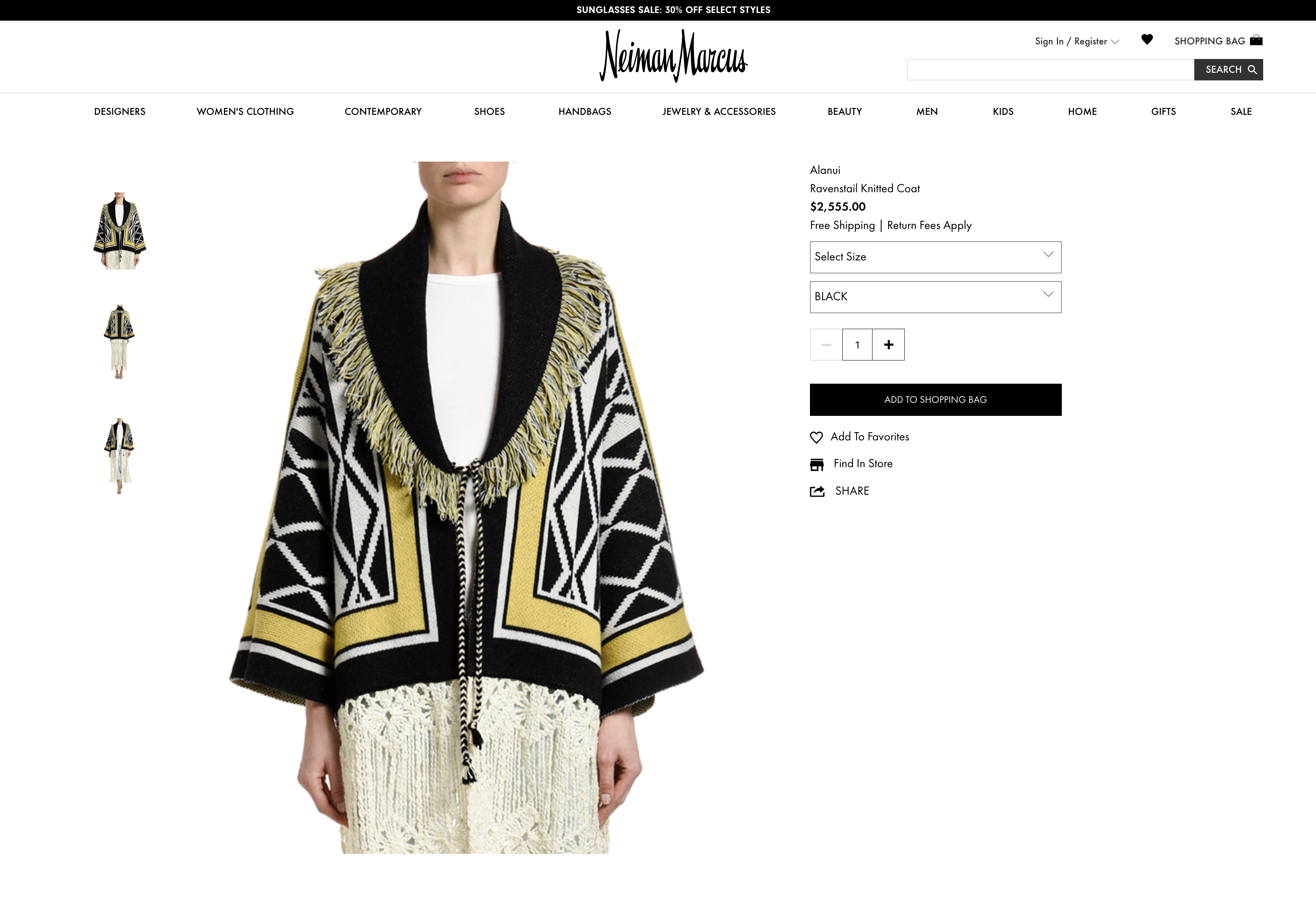

The settlement was announced earlier this month by the Sealaska Heritage Institute. The nonprofit, along with family members of Tlingit weaver Clarissa Rizal, had sued Neiman Marcus and other retailers over their marketing of a $2,555 “Ravenstail Knitted Coat” that appeared to copy the late artist’s design.

Terms of the settlement were confidential. The case remains active, however. The “pre-conditions to dismissal” of the case were expected to be completed by Oct. 1, according to a March 3 motion filed jointly by the Sealaska and defendant attorneys.

Though Neiman Marcus has not admitted wrongdoing, it and the other parties “acknowledge the cultural significance of the issues underlying the development, sustainability and survival of Native cultures, as well as the importance of encouraging creative endeavors through freedom of expression and artistic design,” Sealaska Heritage Institute said in a statement.

Because the settlement terms are confidential, an attorney representing the plaintiffs declined to comment on the specifics of the case.

But in general, there is increasing recognition of Indigenous intellectual property rights, attorney Jacob Adams said.

“This advancement is ever increasing and shifting the discussion of Indigenous intangible resources from one based merely in sensitivity of use — ensuring that outside use of Indigenous resources is sensitive to cultural concerns and contexts — to one of Indigenous ownership and rights to those properties. This change is quite important because sensitivity alone keeps control of intangible cultural resources in the hands of others, whereas under a rights- and property-based understanding, the control of intangible resources remains with the Indigenous group,” Adams said.

There is more use of legal mechanisms to protect that intellectual property, he noted. He cited as examples a collaboration agreement between the Sami People and the Walt Disney Animation Studios concerning portrayals in the movie Frozen 2 and a memorandum of understanding between the Ute Indian Tribe and the University of Utah. He also cited two Arctic Indigenous trademarking or certification systems — Sámi Duodji certification mark and the Inuit ‘Igloo’ certification mark — as examples of current legal protections.

Adams predicts more court cases over Indigenous peoples’ intellectual property rights.

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act has existed for decades, with a history that goes back to the 1930s. However, case law in the U.S. is “woefully underdeveloped,” he said by email. “This does not mean that these groups are not owners of their intangible properties under the law, but merely that we have not had sufficient cases brought, or tested the law adequately, to clearly articulate their rights,” he said.

Another court case aimed at protecting Indigenous intellectual property rights in Alaska recently ended with a sentence.

At about the same time the Ravenstail Knitted Coat settlement was announced, a non-Native man who had owned and operated an Anchorage gift shop was sentenced in federal court for falsely marketing his own carvings as Alaska Native art, a violation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act.

Lee John Screnock, the former owner of the Arctic Treasures gift shop, was sentenced on March 10 to pay $2,500 in restitution to the Indian Arts and Crafts Board and ordered to forfeit retail projects worth $125,00 and to serve five years of probation for a violation of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, federal officials announced.

The investigation of Screnock began in 2015 with the sale of a polar bear skull to an undercover U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agent, a violation of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, federal officials said.

That led to an investigation of crafts sold at his store under the name Savuk, which was a nickname used by Screnock, officials said. The artist referred to as Savuk was portrayed as an Alaska Native from the Inupiat village of Point Hope, according to investigators.

In a pre-sentencing memo, Screnock’s attorneys argued for leniency. They cited his difficult childhood as an orphan in Korea, his challenges raising three autistic children and his remorse for the offense.

They also cited what they said was his good relationship with Alaska Native artists, particularly those who were homeless or recently incarcerated and struggling. “He provided artists with space and tools to create their art and provided daily meals and other assistance,” the memorandum said. “One particular master carver bestowed upon Mr. Screnock the nickname ‘Savuk,’ which means ‘worker.’ Mr. Screnock felt great pride in the receipt of this nickname, and he adopted this signature for his artwork. These carvings were not labeled as having been made by an Alaska Native artist, but he failed to adequately distinguish them, and on two occasions when questioned by undercover officers posing as customers whether Savuk-labeled items were made by a Native artist, Mr. Screnock answered in the affirmative.”

Screnock was also supported by at least one Alaska Native artist, Leon Kinneeveauk, who took over the Arctic Treasures store in 2018. In a letter to U.S. District Court Judge Sharon Gleason, Kinneeveauk — an Inupiat carver from Point Hope — endorsed Screnock’s character and said he had been a strong ally to him and other Native artists.