New Arctic Alaska marine atlas details ecosystems of the changing region

Birds, fish, marine mammals, oil rigs, ships of various sizes and people cross paths in the Arctic waters off Alaska. Now a detailed atlas provides maps that show how the natural world and human activities overlap in the fast-changing marine ecosystems there.

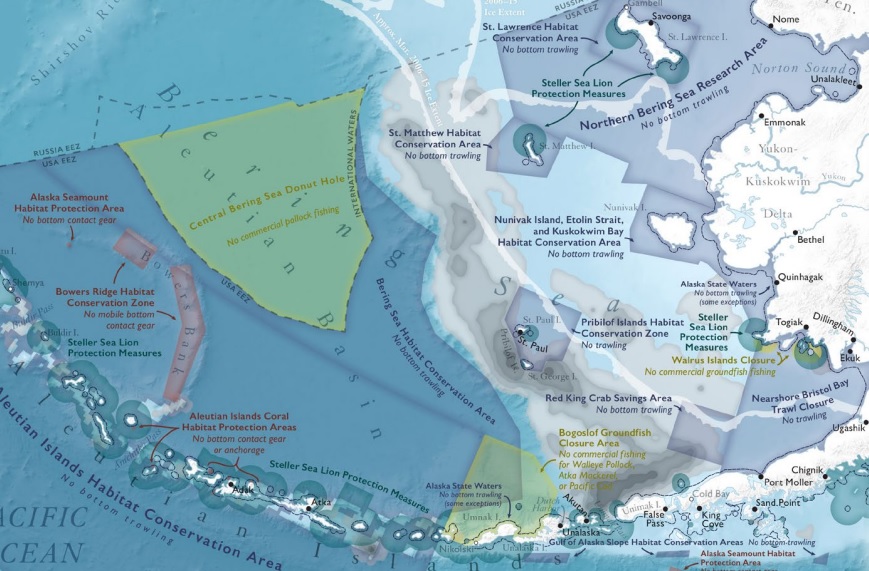

“The Ecological Atlas of the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort Seas,” a project led by Audubon Alaska, holds more than 100 maps that show patterns for everything from the petroleum reserves deep beneath the seas’ floors to the birds flying in the skies far above. It details what it calls the “extraordinary productivity and impressive abundance of wildlife” in the three seas, and more.

Audubon Alaska released the atlas, the product of two years’ work, on Friday.

A special unveiling was held at an evening reception in a packed downtown Anchorage restaurant, where several of the maps were displayed on the walls, but most people are expected to use the atlas’ online version, which is available for free download.

The hope is that people living and working in the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort will use the atlas to help guide their actions and policies, said Audubon representatives.

The atlas should help government agencies get a holistic view of the region, said Melanie Smith, Audubon Alaska’s director of conservation science.

“Oftentimes, the government agencies tend to stick with their own missions, their own administrative boundaries,” Smith said at the Friday reception. “There isn’t a government agency that does it all.”

The atlas uses information from government agencies, like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages migratory birds, walruses and polar bears; the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which manages whales, seals and fisheries in federal waters; and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, which manages oil and gas operations in federal waters. It also uses information from nongovernmental agencies, Alaska Native organizations, international organizations and academic studies.

“When you pull it all together, you start to see new patterns,” Smith said.

Atlas users can identify biological hot spots and overlay those with human-use patterns and potential threats, she said.

This is Audubon’s second version of a comprehensive Arctic Alaska marine atlas. An earlier version, the Arctic Marine Synthesis, was released in 2010.

The new atlas has more complete and updated information and an expanded geographic scope, including all of the Bering Sea to the south and the Canadian Beaufort to the east, Smith said. More topics are included, particularly in the areas of human uses, she said.

Effects of climate warming, such as the changes in sea ice, are detailed in the atlas. But climate change, the most prominent threat, is not the only “pressure point,” the document points out.

“Retreating ice brings greater access and increased vessel traffic, which comes with associated risks: shipwrecks, chemical spills or leaks, and ship strikes and noise disturbance to wildlife. The Arctic is also vulnerable to the effects of hydrocarbon extraction and transportation,” the atlas’ conservation summary says.

Government agencies participated in the atlas creation and appear to be interested in using it, Smith said. Experts from BOEM, for example, acted as peer reviewers for the document, she said.

Audubon and its project partners hope the atlas will be consulted as BOEM draws up plans in accordance with the Trump administration’s push for more offshore oil development, Smith said.

Career administrators in the agencies have been receptive, despite the political changes at the top, she said. But President Trump and his political appointees are dismissive of climate science and environmental regulations, and whether they will heed the lessons provided by the atlas is unclear.

“To have science permeate the decision-making process, it feels difficult,” she said. The career administrators are the same people who were working in the agencies prior to the Trump administration and are “doing good work,” she said.

“That doesn’t mean the decisions will follow the science,” she said.