New book on polar shipping offers key guidance to mariners

“Never take the ice for granted."

Ask Capt. Duke Snider why mariners in Canada’s Arctic need to be well-informed, and Snider’s answer is clear.

It’s because they’ll find a maze of channels and passages that, “even without ice, are navigationally challenging,” Snider, an ice navigation expert with 40 years of experience in polar waters, told Nunatsiaq News.

“The ice adds a greater complexity and risk,” Snider said.

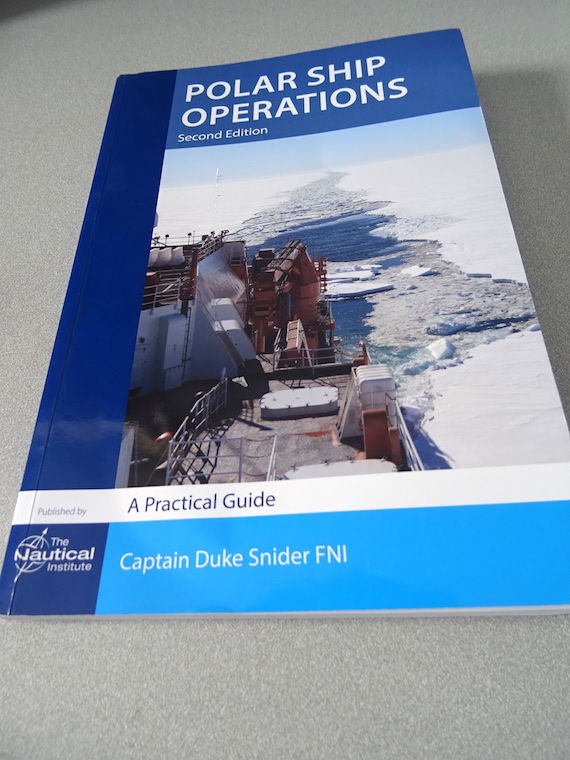

The new edition of his 2012 book, Polar Ship Operations, aims to make travel in the Arctic and the Antarctic waters safer.

“It’s written for anyone” piloting substantial vessels, as well as those sailing smaller craft, he said. “I have received thanks from private yacht owners that have used it.”

Ship traffic has increased through the Northwest Passage since the last edition of Polar Ship Operations, published by the Nautical Institute, the international body for qualified seafarers.

The number of Northwest Passage transits almost doubled from 2016 to 2017, to 33 ships of all sizes, according to the Scott Polar Institute’s latest tally.

The new edition of Snider’s book won’t be a cure-all for those expecting a quick and easy passage through ice-covered waters, said Adm. Nigel S. Greenwood in his foreword to Polar Ship Operations, but it offers lots of important knowledge.

That’s essential because operating ships in polar waters requires a mix of knowledge, skills and awareness.

And “there will be new and less experienced ship operators in Arctic waters in the forseeable future,” as these waters open up due to the presence of less ice and more resource development, added Tero Vauraste, CEO of the state-owned Finnish icebreaking company, now vice chair of the Arctic Economic Council, in his foreword to Polar Ship Operations.

The latest version of the 150-page book includes an analysis of the Polar Code, which entered into force in January 2017, and it offers details about the Arctic Council’s agreements on search and rescue operations and marine pollution.

Other chapters touch on climate change, ice, cold weather, health and safety, planning and ship handling in ice.

On that last topic, Snider offers up four rules, which, to a non-mariner, who might be inclined to crash through ice, seem a bit counterintuitive:

• Go slowly because excessive speed leads to damage.

• Once in the ice, keep moving, even if slowly.

• Work with the ice movement, not against it.

• Know your ship’s maneuvering characteristics.

Other important things to remember: Always look for an ice-free route and avoid besetment (that is, being trapped in the ice).

Regardless of global climate change, ice remains a challenge to all but the “most robust” ice strengthened vessels throughout the year, Snider said, with Arctic ice conditions remaining highly variable annually, seasonally — and even daily.

“These regions are remote, far from the usual lifelines. One must come fully prepared for dealing with issues on one’s own. The second and arguably greater issue is the presence of ice,” Snider said.

“Never take the ice for granted and don’t think for a moment that it’s ice free,” is Snider’s last word on the takeaway messages of his book, which can be ordered online from the Nautical Institute, which he also heads.