New fish species are moving into the Canadian Arctic as its waters warm

Two sockeye salmon caught near Cambridge Bay in Nunavut offer "a glimpse of what is coming."

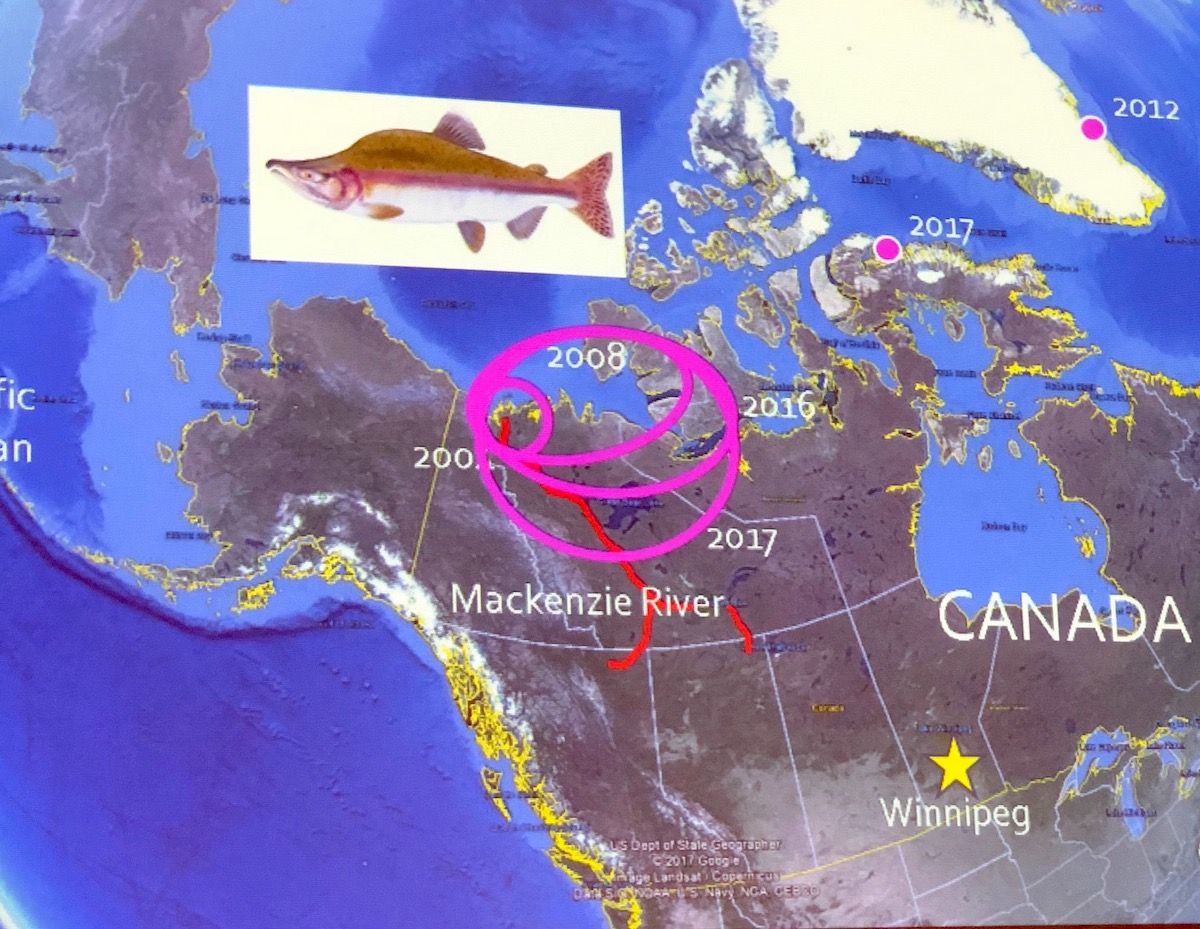

In 2016 and 2017 commercial fishers near Cambridge Bay in Nunavut were surprised when they pulled in sockeye salmon — because they were expecting to see only Arctic char.

While these are just two fish, found far from their usual home waters, the two salmon are likely an indication that Pacific salmon will continue to spread their range from the Pacific Ocean.

It’s “a glimpse of what is coming,” said Karen Dunmall, an aquatic science biologist with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans at last week’s ArcticNet conference in Ottawa.

Sockeye salmon, which have already established themselves along the coasts of the Alaska North Slope, were first spotted near Inuvik in the Northwest Territories in 2004.

For now, it’s probably too cold for salmon to spawn near Cambridge Bay because “they need to find a place that doesn’t freeze in the winter,” Dunmall said, and salmon appear to like slightly warmer water to spawn in than Arctic char.

“This will separate salmon and char in most rivers, but char that find groundwater springs of 4 degrees Celsius could face competition if salmon colonize the river,” she said.

Dunmall’s key points remain simple: Salmon are now in the Canadian Arctic and they are increasing in the Canadian Arctic.

And she said community-based monitoring is the way to track changes in the fish population.

Traditional knowledge and science make a “powerful platform to assess rapid change,” she said.

To that end, Dunmall helped prepare a “guide to identifying salmon and char in the Arctic,” in English and Inuktut, with lots of colored illustrations, so that hunters and fishers can recognize salmon if one comes up in a net.

Salmon are the most visible migrants to Nunavut waters. But that could also change, according to Maxine Geoffroy from Memorial University’s Centre for Fisheries Ecosystems Research.

Geoffroy’s research points to a future east-west passage of fish in the High Arctic islands. The few Arctic cod found now in the slow, cold waters of the southern Kitikmeot region suggest that this area acts as a barrier between populations in the Beaufort Sea and Baffin Bay.

But Geoffroy said the M’Clure Strait and Viscount Melville Sound are deep enough to contain Atlantic waters. These could provide a possible habitat for Arctic cod as ice concentrations of less than 50 percent in the summer open up exchanges through the Parry Sound, the northernmost waterway of the Northwest Passage.

In Geoffroy’s ArcticNet presentation on fish in the polar night, he spoke about how in the North Atlantic fish like redfish and capelin have already moved north into the Arctic waters above Norway.

But even if these waters continue to warm, the polar darkness could present problems to new fish species, he said.

“The ability to reproduce during the polar night seems to be a key adaptive trait of Arctic fishes,” Geoffroy said.

Polar fish such as Arctic cod, ice cod and Greenland halibut like to spawn in the dark, and the hatching takes place in the spring when there’s lots for the fry to eat.

Arctic fish that thrive in the polar winter usually have large eyes, as well, which are good for seeing in the dark, Geoffroy said.

Catches of redfish and capelin in Arctic waters suggest that these newcomers may have trouble feeding in the polar night, because they have been found with empty stomachs.