New research reinforces view of link between rising Arctic temperatures and extreme cold farther south

As if melting glaciers, thawing permafrost and starving polar bears weren’t enough, scientists are finding that the effects of climate change in the Arctic are even more complex – and far-reaching – than we thought.

New research suggests that warm spells at the top of the world can, surprisingly, cause unusually cold weather in parts of North America – and that could be hurting plants, damaging agriculture and even affecting the amount of carbon dioxide that goes into our atmosphere.

Plus, it further reinforces a controversial but persistent theory suggesting that the fast-warming of the Arctic could be causing weather extremes in the heavily populated mid-latitudes as well.

The new study, just out Monday in the journal Nature Geoscience by a team of researchers from South Korea, China and the United States, finds that warmer-than-usual springtime temperatures in the Arctic Ocean are followed by colder-than-usual temperatures across much of North America, as well as a reduction in precipitation in some parts of the southern United States. And these conditions are also associated with a reduction in plant growth and development, in some cases even leading to reduced crop yields.

“This study adds to the growing pile of evidence that the indirect effects of Arctic meltdown will affect us all in surprising ways,” said Arctic climate expert Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, who was not involved with the new research, in an email to The Washington Post.

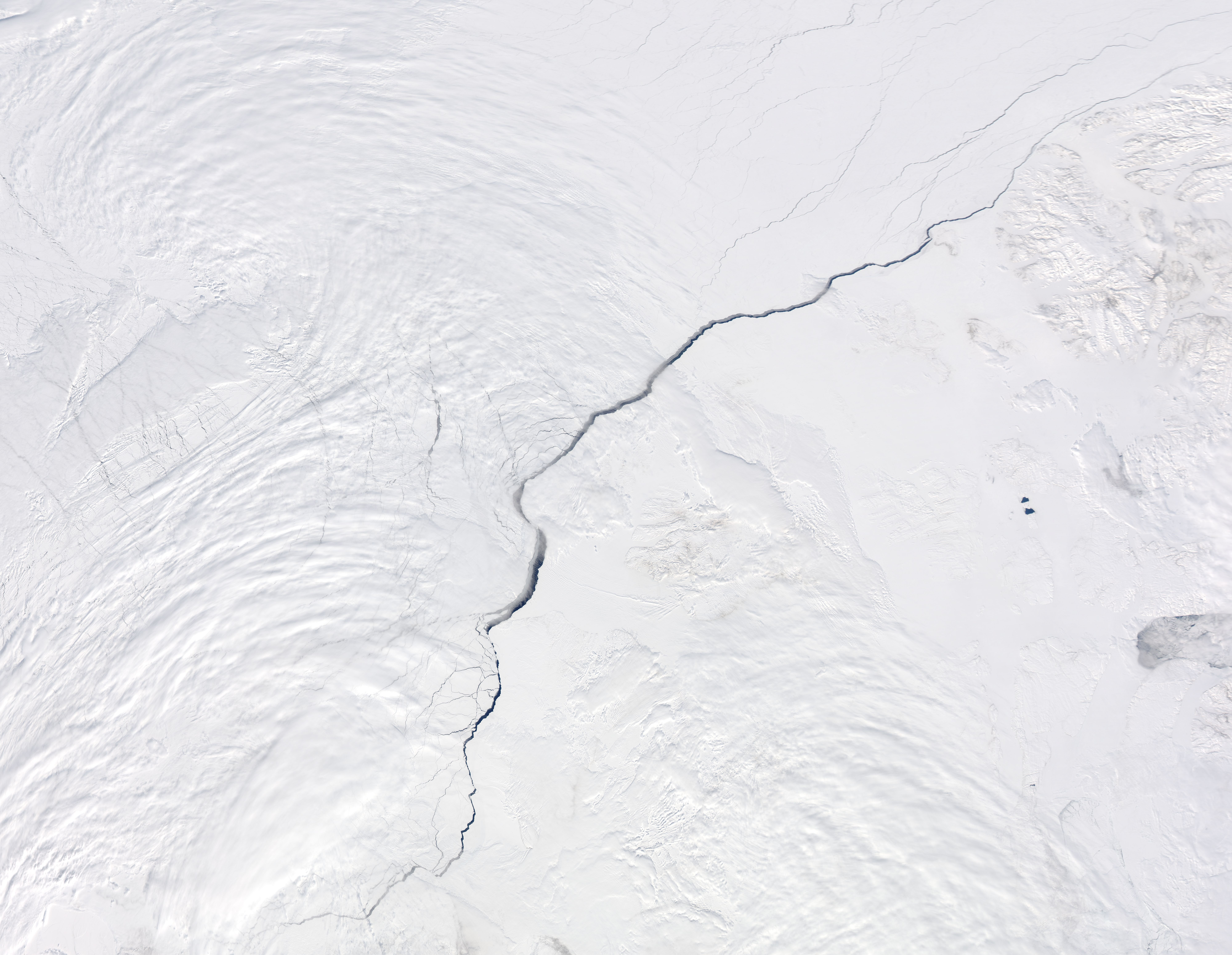

The new study builds on a previous paper, published by some of the same authors two years ago, which explored the link between unusually warm conditions in the Arctic Ocean and unusually cold winters in both East Asia and North America. This study, along with other similar research conducted in the last few years, suggests that warming ocean temperatures and declines in Arctic sea ice can cause atmospheric changes that significantly affect weather patterns in other parts of the world.

Some scientists have suggested, for instance, that Arctic sea ice declines are contributing to longer, fiercer winters in North America by causing a shift in the so-called polar vortex, the large patch of cold air flowing around the North Pole. Some of Francis’ own recent research has focused on the potential for Arctic sea ice declines to alter the circulation of a fast-flowing current of air known as the jet stream, causing it to weaken. However, these ideas remain controversial and debated within climate science.

The study from two years ago – the precursor to this week’s new research – suggested that warming over the Arctic Ocean is accompanied by a change in the circulation of winds, which cause more cold air to flow into North America. But the researchers didn’t want to stop there.

“As an extension of the paper, we thought the Arctic warming can eventually influence on the ecosystem over North America by modulating climate factors in controlling vegetation growth,” said climate scientist Jong-Seong Kug of Pohang University in South Korea, one of the new study’s authors, in an email to The Washington Post.

In the new study, the scientists examined temperature data from both the Siberian-Chukchi Sea and the North American continent between 1979 and 2015 to confirm that unusually warm springs in the Arctic were associated with cooling in much of northern North America, as well as drying in certain areas, particularly the south-central United States. Next, they examined satellite data on plant cover over the last few decades, as well as data from on-site measurements of the carbon dioxide and other gases produced and exchanged by vegetation across the continent.

These data suggest that plant productivity declines in many parts of North America during the warm-Arctic years, with the greatest effects seen around the Great Lakes Basin – likely because the vegetation in this region is particularly sensitive to the cold, the researchers note. They also note that there are some severe declines observed in the south-central United States as well, possibly caused by the decrease in precipitation. Model simulations supported the idea that these changes in vegetation were caused by the unusual climate conditions.

The researchers also evaluated national crop yield data for corn, soybeans and wheat and found that agriculture suffers in some areas as well during these unusual years. The Great Plains region tends to experience declines in all three crops, and Texas has seen particularly severe declines in its corn harvest, with its productivity shrinking as low as 20 percent of its typical yield.

“Crop success depends on a complicated interplay between temperature, precipitation amount, and even timing of snowmelt, and it appears from this work that recent Arctic warming may be disrupting normal patterns,” noted Francis, the Rutgers University scientist.

These declines in plant production are accompanied by a reduction in the amount of carbon the vegetation is able to store – a potential major blow to the climate. Forests are some of the world’s most important carbon sinks, sucking up massive amounts of carbon dioxide each year that would otherwise go straight into the atmosphere. But the new study estimates that the carbon storage ability of North American vegetation declines by up to 14 percent during the warm-Arctic years.

For now, all of these effects seem to be temporary, limited to the years when the Arctic experiences unusually warm conditions. And how the overall carbon cycle will respond to continued Arctic warming in the future is unclear, noted researcher Ana Bastos of the Laboratory of Climate Science and the Environment in Gif-sur-Yvette, France in a comment on the new research, also published Monday in Nature Geoscience. There are many other factors that affect the flow of carbon between plants and atmosphere that will need to be more thoroughly investigated.

But the researchers do believe that the effects on plant productivity will grow more severe in the future as Arctic warm spells become more frequent.

“There will be more frequent and stronger cold events [in North America], induced by the Arctic warming,” Kug said. And the models predict that the same levels of cold will produce much stronger plant declines in the future, suggesting that vegetation may become more and more sensitive to temperature damage as these events occur more often.

While the news sounds grim, Francis points out that investigating the connections between Arctic and North American climate variations may be able to help farmers make better predictions about their crop yields in advance. And the study may also help challenge a long-standing idea – often propagated by those skeptical of the negative impact of climate change – that global warming will be a positive influence on plants all over the world.

Indeed, while warming has been associated with an increase in vegetation at the poles, and spiking carbon dioxide levels may boost plant productivity in certain places, the paper clearly indicates that the effects of climate change are not always so simple. And the changes that occur in one small part of the planet can have an echoing influence around the world.