Newly discovered prehistoric bird lived near a balmy North Pole

The North Pole wasn’t always a winter wonderland. Rewind 90 million years, and scientists think it was probably as warm as parts of Florida.

A new clue supporting that idea is a fossilized wing bone belonging to a newly discovered prehistoric bird found in the Canadian Arctic. The duck-size creature looked like a cross between a sea gull and a cormorant, but with a beak full of teeth. It could both fly and dive, and it most likely lived alongside turtles, crocodilelike reptiles and a whole lot of fish.

“This was a hyperwarm period, a real spike in temperatures where we think even during the winter there wasn’t freezing water,” said John Tarduno, a geophysicist from the University of Rochester. “Tingmiatornis arctica adds to this picture that we have of this incredibly warm Arctic 90 million years ago.”

Tarduno and his team published their findings Monday in the journal Scientific Reports.

Scientists aren’t sure why Earth was stifling hot for several million years during the Cretaceous period, but according to Tarduno, the prevailing hypothesis is that the atmosphere was filled with heat-trapping carbon dioxide, most likely the result of extraordinary volcanic activity. The resulting greenhouse effect would have transformed the polar ecosystem into a place where Tingmiatornis arctica and its prey could thrive.

The warming period, known as the Turonian age, is estimated to have lasted from 93.9 million to 89.8 million years ago. At its coldest, it is estimated that the Arctic got around 57 degrees Fahrenheit (about 14 degrees Celsius).

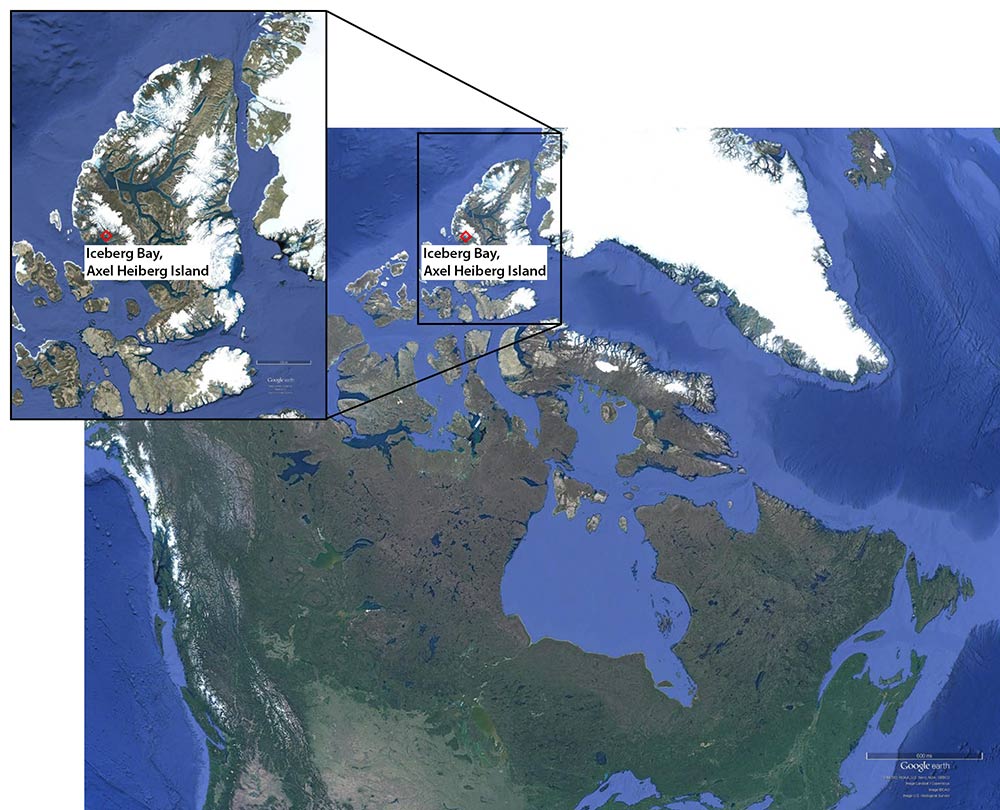

In his time exploring the snowcapped brown hills and thick glaciers of Nunavut, in the Canadian Arctic, Tarduno has come across two wing bones belonging to this species of bird. He uncovered the first humerus in 1999. It was relatively small and he didn’t pay it much mind until he found a second, larger bone a few years later. But even the second humerus didn’t catch his attention at first. Instead, he and his team were preoccupied with a large turtle shell that was on the other side of the same rock.

“We took it back to camp and went, ‘Oh, wait a minute, there’s another spectacular fossil on the other side,’” Tarduno said.

After finding the bones, they turned to their colleague Julia Clarke, a paleontologist from the University of Texas at Austin, for further analysis. She knew the bones belonged to a group of birds called ornithurines, which includes all living birds and their closest extinct relatives. But by studying the unique marks on the points on the bone where it was once attached to muscle, she was able to determine that the fossil belonged to a prehistoric bird unlike any that had previously been discovered.

Clarke was also able to determine that the bird was a capable flier because of the size and shape of the bone, and that the bird most likely dove in the water because of the thickness of the outermost layer, known as the cortical bone.

She said the finding might help paleontologists understand an even bigger mystery.

“We can’t explain why some flying dinosaurs, which we call birds, went extinct right alongside all the other dinosaurs,” she said, “and why only parts of the ornithurines survived to the present day.”

By collecting more fossils of ornithurine birds like Tingmiatornis arctica, paleontologists can better understand what helped this lineage of birds survive the extinction event 66 million years ago when three-quarters of all animal and plant life perished.