Nunavik’s biggest park looks to diversify visitor experience

UMIUJAQ — It’s the end of May and the temperature has climbed to 24 C (75 F) in Umiujaq, the second most southerly community in Nunavik and situated along the eastern Hudson Bay coast.

Umiujaq is the unlikely hot spot in Quebec. The sea ice on Hudson Bay has already broken up and drifted away from the shoreline, shifting the view from white to a deep blue.

For hunters, campers or hikers, this is a sweet spot — the time of year where you can enjoy the heat before the mosquitos and black flies arrive.

Umiujaq, population 440, is the base for Tursujuq park, one of four established Quebec national parks in Nunavik and the largest in all of the province, at 26,107 square kilometers (about 10,080 square miles).

Unlike Nunavik’s other parks, like Pingualuit or Kuururjuaq, which require transport by plane or snowmobile from the closest communities, visitors can practically walk from Umiujaq to the park’s entrance.

A quick all-terrain vehicle ride takes you to an access road that leads into the park.

At the end of May, there’s still enough snow and ice to make the park itself inaccessible but an hour hike up over a rocky crop gives you a wide view over Tasiujaq Lake, where the cliffs of the Richmond Gulf rise up over a large inland bay.

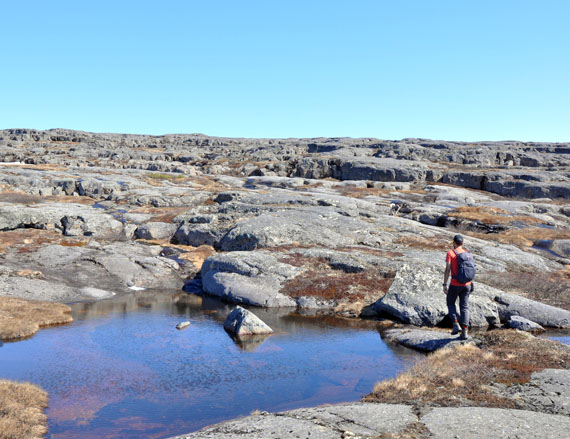

The view is just a tease for what the sprawling park offers; Tursujuq is home to sweeping cuestas, waterfalls, Quebec’s second largest natural lake (Clearwater) and an expanse of both tundra and taiga.

“We have a beautiful landscape,” said Charlie Tooktoo, who’s served as Tursujuq’s director for just over a year now.

“We’re working hard to have more tourists come here. So we’re getting to be known.”

Tursujuq staff delivered the park’s first winter package last March, something the park hopes to offer more of in future.

Park staff are currently working on a cross-country ski trail system through Tursujuq. One of its new visitor packages is an 80-kilometer ski expedition that winds through four camp sites on the northeast side of Lake Tasiujaq.

In 2017, park staff are also hoping to test out mountain biking as a visitor experience, as well as mapping the river to Clearwater Lake to help visitors who want to travel that part of the park by canoe and kayak.

“It looks very promising,” Tooktoo said.

The park is planning to host more than 100 visitors this summer, when cross-country skis are traded in for kayaks as the preferred method of transport.

Tursujuq’s visitors hail mostly from Quebec, some from the U.S. and a few from France, but the park is also attracting more Inuit.

That’s in part thanks to Nunavik Parks’ Weekends in the Parks packages, which offer a limited number of discounted weekend trips to Nunavimmiut during summer weekends.

Nunavik Inuit already get free access to the region’s parks, but the Nunavik Parks Beneficiary Access program also reimburses a portion of the cost of air travel to get to a park or a gateway community.

But Tooktoo prides himself on hosting visitors who are new to Inuit culture; despite the scenic views, it’s the culture that many are interested in, he said.

When southern visitors arrive, park staff host a cultural night at the park pavilion in Umiujaq, showcasing throat singing, Arctic Winter Game demonstrations and stone carving. Guides might take a group out mussel-picking.

“They like the cultural activities,” Tooktoo said. “Staying in a tupik (tent) is a big thing for them.”

That translates into spin-offs for the community — Tooktoo said the park employs five Inuit staff; there’s a new hotel in Umiujaq to cater to tourists and community artists and athletes also take part in demonstrations and cultural nights.

But not everyone thinks the park was in the best interests of Umiujaq, the only Nunavik community that hasn’t seen any population growth in recent years.

Umiujaq’s former and first-ever mayor, Noah Inukpuk, said he never supported the creation of Tursujuq park.

“I was always thinking: it’s the future land of the people living here,” he said. “I was thinking the land would be there for economic development—something people can benefit from more than a park.”

Inukpuk said the process to identify and create the park happened more at the regional and provincial level and did not include enough input from the community.

“Even though we have a right to hunt, they still have to replace the land they took from the community,” he said.

“It has created a few jobs, but there’s been no major benefit for the community.”

Tooktoo disagrees.

“Even if it’s small, it’s helping people out,” he said.

There are still limited spaces available for Weekends in the Park packages left for the summer. Go to the Nunavik Parks website for more information on visiting Tursujuq.