Nunavut iron mine proposes bigger ships, no spring ice-breaking

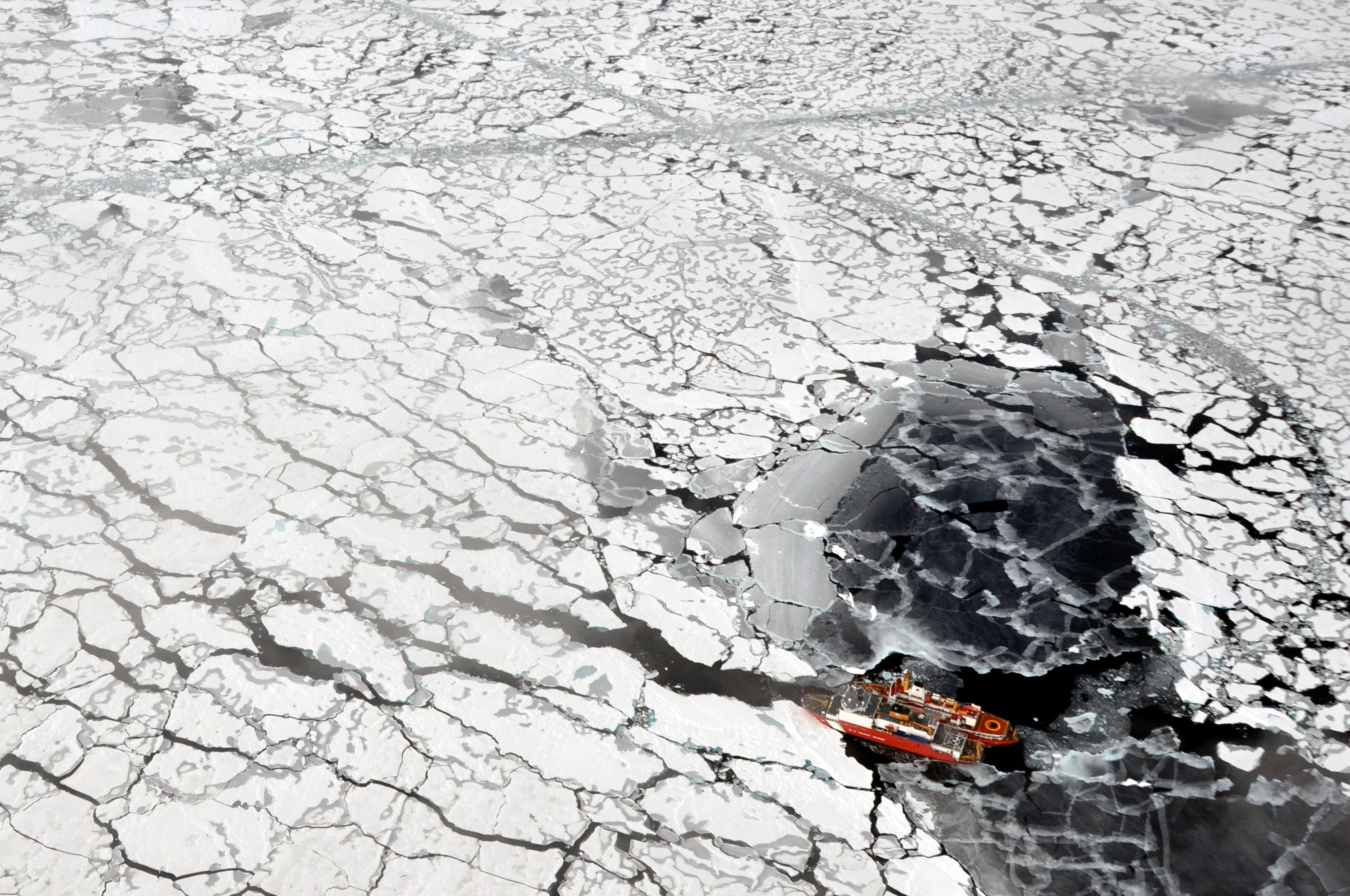

Baffinland Iron Mines Corp. has revised its latest plans for the Mary River iron mine expansion, proposing to increase open-water shipping out of Milne Inlet with bigger ships, but abandoning an unpopular plan for ice-breaking during the busy spring hunting period.

To fill those ships, Baffinland is proposing to transport 176 railway cars and five diesel locomotives north and build a railroad line from the mine site to the Milne Inlet port, roughly following the same path as the current tote road used for ore trucks.

Those revisions, filed with the Nunavut Impact Review Board in response to questions the board had about its Phase 2 Second Amendment project description, contain two overriding themes: Baffinland must ship more ore and make more money to be viable, but they can’t do by breaking ice and shipping in spring.

“We’ve had community workshops based specifically on this issue [of spring ice breaking]. I’m hopeful what people will take away from this update is we’ve listened, we haven’t just gone on blindly,” Todd Burlingame, Bafffinland’s vice president of sustainable development, said Dec. 2.

“I’m very pleased with the improvements,” he added. “It’s really informed by community engagement and by operational experience. In 2014, we just didn’t have that real-time experience in shipping, mining and trucking.”

Joe Enook, Nunavut MLA for his native Pond Inlet riding of Tununiq, said he hasn’t had time yet to read through the entire update.

But Enook said he was “pleasantly shocked and surprised” that Baffinland had listened to the wishes of his constituents.

“Regulated, if I must, I would much rather have more shipping in summer than to have ships during dead winter,” Enook said.

The thing is, no matter how Baffinland gets their iron ore to overseas markets, Pond Inlet will see the greatest impact, Enook said. And that’s worrisome.

He said about 56 ships—cargo resupply, cruise ships and ore carriers—chugged past his community of about 1,600 people this past summer. Pond Inlet is in a transformation, he said: Traditional lifestyles are changing, but people are getting training and jobs.

And, with no crystal ball to foresee whether the benefits will outweigh the costs, it’s tough to know how to feel about that.

“It’s a ‘catch-22.’ In this day and age, do we want progress, meaning economic development, mining development, jobs for our young society?” he asked.

“It’s a terrible position to be in, to think there’s potential for 100, [or] 200 years of work for the people of Pond Inlet, at this mine alone, versus my ability not to be disturbed when I go out seal hunting. It’s a real balancing act.”

Chris Debicki, Nunavut project’s director for the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Oceans North Canada, applauded the decision to limit iron ore shipping to the open-water season given the risks to marine mammals of icebreaking during winter months.

“Recent research has shown that seal pups that den on the ice floes would have been especially vulnerable to harm by icebreakers,” Debicki said. “This move is especially important given that ships will also travel through the proposed Lancaster Sound marine conservation area.”

The marine conservation area, which would likely have restrictions on things like marine traffic, includes Baffinland’s port at Milne Inlet.

In order to meet the maximum shipping target of 12 million tonnes of iron ore—as proposed in the company’s Phase 2 proposal—and make Baffinland profitable again, the company has to make changes, Baffinland’s update clearly says.

It’s not known exactly how much the railway cars, 100 kilometres or so of railway supplies and construction, and the accompanying infrastructure, would cost, Burlingame said. But it will be “well below” the estimated cost of the original plan, which was to build a southern railway to Steensby Inlet, 50 km further, at a cost of $5 billion.

And instead of trans-shipping—that is, having smaller ships transport ore to larger ships at an offshore location as planned—Baffinland now proposes bringing Cape-size ships into its Milne Inlet port.

Cape-size ships, so called because some are too big to fit through the Panama and Suez canals and so must traverse around the southern capes of Africa and South America, are the largest bulk carriers in the world. These ships can hold 250,000 tonnes of deadweight, according to Baffinland’s update.

The length of those ships ranges anywhere from 250 metres and more than 300 metres— roughly three football fields long.

The mining company suggests using those and other smaller ships which can carry 55,000 to 90,000 deadweight tonnage.

While a tundra railroad will likely cost billions, Burlingame said the investment is worth it for the long-term savings.

Running a half-dozen trains per day on reliable, maintained track versus a couple of hundred truck loads on an all-weather road which needs constant upkeep is more efficient, more cost-effective—and, he suggested, better for the environment.

“It’s a huge undertaking,” Burlingame said. “But I think it’s a real amazing proposal and, if it gets approved, it will be a legacy project that will be around for a long, long time.”

There are still possibilities for animal strikes and fewer jobs for Inuit truck drivers, but jobs for local people can be found elsewhere, in “other aspects of the production, transport and shipping of ore to overseas markets,” the project update said.

The update does leave the door open for possible ice-breaking through winter if Baffinland needs supplies or equipment delivered, Burlingame said. But communities would be notified in advance.

Burlingame cautioned that this is only a project update and that more details of their plans, with a cost-and-benefit analysis, will be contained in a still-to-come environmental impact assessment, to be filed as soon as the company get the green light from the NIRB.

Enook said he’s grateful that Nunavut leaders had the foresight to negotiate for the creation of the NIRB within the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement because the board has the expertise to weigh technical, scientific and Inuit evidence on behalf of communities which don’t have that kind of capacity.

“We are being bombarded with all this stuff,” he said. “At the end of the day, we stand strong and do the best we can for our community and our environment. Because we have to,” he said.

The Mary River mine, located about 150 km from Pond Inlet, contains an iron ore grade estimated at 67 per cent, one of the highest in the world.

Truck traffic along the frozen tote road will continue this winter, Burlingame said, as ore is stockpiled and equipment serviced and maintained for next summer’s shipping season.