Nunavut premier condemns Russian rocket launch, demands it be halted

Nunavut Premier Peter Taptuna has joined with the Inuit Circumpolar Council to demand that the governments of Canada and Denmark tell Russia to keep its toxic space junk out of Inuit marine waters.

“We condemn Russia’s actions and demand that this launch be halted. We can’t afford to have unknown amounts of hydrazine fuel land in largest polynya in the northern hemisphere,” Taptuna said in a statement released Oct. 6

On Oct. 5, Inuit Circumpolar Council had made a similar demand, issued in reaction to Russian plans to launch an old, re-purposed Russian SS-19 intercontinental ballistic missile carrying a European Space Agency satellite into orbit Oct. 13.

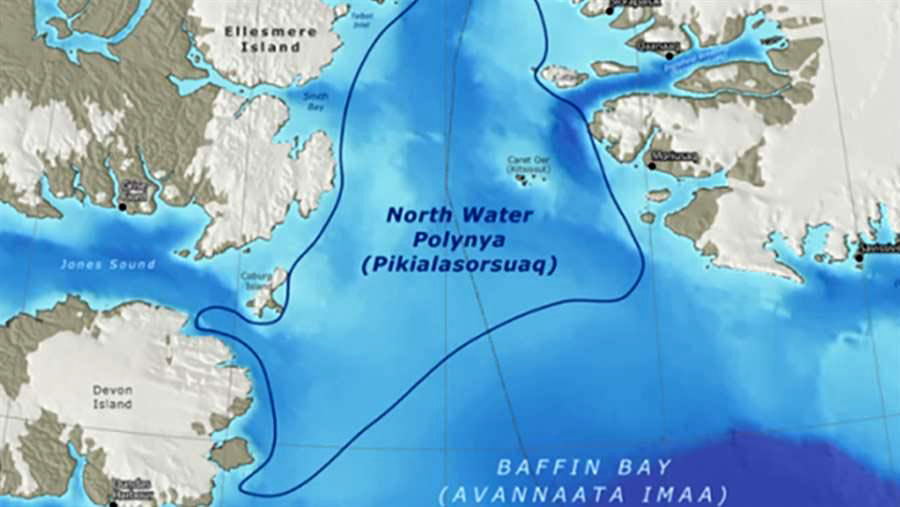

The rocket’s second stage contains an unknown quantity of hydrazine, an extremely toxic fuel that could end up falling into the waters of Pikialasorsuaq, also known as the North Water polynya, between Ellesmere Island and Greenland.

“The fact that space agencies are willing to use the Pikialasorsuaq/North Water [polynya] as a toxic dump underscores the pressing need for local management of this sensitive ecosystem. These marine waters are in fact our source of food,” Nancy Karetak-Lindell, the acting chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, said Oct. 5 in the ICC statement.

The old SS-19 rockets date to the Cold War and were originally designed by the Soviet Union to carry nuclear warheads. Following the arms control agreements of the 1980s and 1990s and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian now uses many of its old SS-19s for commercial civilian purposes.

Because of the fuel’s extreme toxicity, many countries in recent years have been transitioning away from the use of hydrazine.

Karetak-Lindell is also chair of an ICC commission created in 2016 to consult Inuit in Greenland and Canada about the huge, 85,000-square-kilometer (about 33,000-square mile) polynya.

It’s an ecologically rich zone of open water at the northern end of Baffin Bay that feeds numerous marine mammals and birds within its unusually warm microclimate.

The Pikialasorsuaq Commission, after visiting Inuit communities in Canada and Greenland, eventually recommended the area should be managed by Inuit.

They now say the Russia rocket launch should be delayed until the impact of dropping space junk into the polynya can be studied.

“We urge the governments to apply the precautionary principle to this issue and in the absence of certainty about the health and environmental risks of the residual hydrazine fuel and metal debris that will fall into this marine region, the launch must not proceed,” said Kuppik Kleist, the Greenland member of the commission.

In his statement, Taptuna agrees that Canada should act to stop the rocket launch.

“Canada has a duty to protect our citizens and marine environment from foreign actions that have the potential to cause ecological contamination and health impacts as a result of residual hydrazine fuel and metal debris that falls into the marine area,” Taptuna said.

And he also said he has communicated with Canada’s prime minister on the issue.

“I have reached out to Prime Minister Trudeau to express Nunavut’s concern and disappointment,” Taptuna said.

Michael Byers, an expert in international law and a professor at the University of British Columbia, said in a recent paper, co-authored with his son, Cameron, that the Russian rocket launch is likely inconsistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Canada, Denmark, Norway and Russia are all signatories to that treaty, Byers said.

At the same time, the rocket’s second stage will fall into areas lying within the 200-mile exclusive economic zones of either Canada or Denmark, which means the environmental laws of those countries would automatically apply to any toxic materials dropped into the waters of the Pikialasorsuaq polynya.

This means that Russia, as well as France and the Netherlands, which are involved in the European Space Agency launch, may carry legal liabilities under international law, Byers said.

Another affected area is the Barents Sea, within Norway’s 200-mile exclusive economic zone. That’s where the first stage of the rocket is likely to drop.

But although NOTAMs—or notices to aircraft pilots—are issued in advance of these Russian rocket launches, people who live in the area never receive any advance warning.

“Inuit living near the debris field in Baffin Bay, and who often travel there while hunting, do not receive notice from any source,” Byers said.

Byers paper also cites studies that found that U.S. aerospace workers who came into contact with nuclear missiles fueled by hydrazine suffered numerous health problems including different types of cancers, and that rocket stages dropped on the land in Russia and Kazakhstan have polluted “vast territories.”

Larry Audlaluk, a hunter and former mayor of Grise Fiord, said he’s worried about the upcoming rocket launch.

“Not only do we [Inuit] on both sides of the largest open water [area] depend on the wildlife for sustenance, but the distance between the two countries is very small. The closest gap further north between the two islands is only 32 kilometres,” Audlaluk said.

The ICC also protested the last Russian rocket launch, which threatened to drop toxic hydrazine into Baffin Bay in June 2016.