Nunavut reaches for the stars with the territory’s first satellite

“It should feel like you’re 400 kilometers above the surface of the Earth”

For Jason Carpenter, Arctic College’s joint satellite project is more than the territory’s first space mission — it’s an inspiration point.

Carpenter is the senior instructor of the college’s Environmental Technology Program, and coordinates the Nunavut side of the Western University–Nunavut Arctic College CubeSat project.

By partnering with the Ontario university, Carpenter hopes that Nunavut’s “first foray into satellites” will end up being one step of a much larger journey.

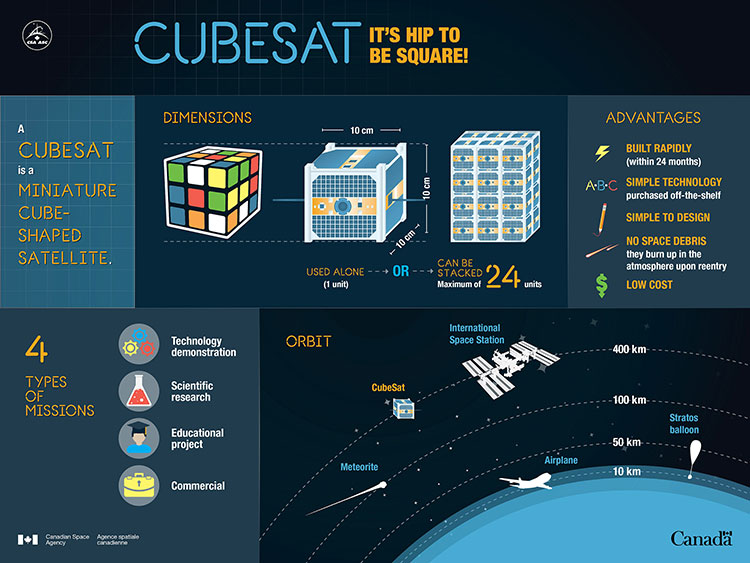

The Canadian CubeSat Project is an initiative of the Canadian Space Agency. In 2017, CSA asked post-secondary schools for proposals for a miniature cube-sized satellite, also known as a CubeSat, that professors and students could design and build.

The CubeSats—which are about 1 kg and the size of a Rubik’s cube, but can be stacked to be made bigger—are often used by school programs, since the satellites are quicker to build, require simpler designs and are cost efficient.

In 2018, 15 projects were awarded grants by CSA, with schools from every territory and province taking part.

The objective of each CubeSat differs between participants, and can range from themes like space exploration to asteroid geology. But the Ontario–Nunavut team took a different approach: by placing two, 180 degree cameras on either side of the CubeSat, the team will get a 360 degree view and create virtual reality glasses using those images.

“So you’re used to seeing beautiful images of space from the space shuttle, from various telescopes,” Carpenter explained. “But to actually have a 360 degree view and see how things are all interrelated … that’s not something most people have experienced.”

“[Basically] you’ll be able to turn around and move and it should feel like you’re 400 kilometers above the surface of the Earth.”

Viewers could look around and watch celestial bodies, the Moon, the Earth and more.

CubeSats are planned to launch around 2021 or 2022 from the International Space Station. The Ontario–Nunavut satellite will have up to 12 months to gather images.

Jayshri Sabarinathan, the project lead and part of Western University’s Centre for Planetary Science and Exploration, as well as the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, describes the relationship between the two schools as “outreach but outreach plus a little bit more.”

Due to their aerospace and engineering programs, Western University is the technical lead on the project. Throughout the past year, their students have been creating a preliminary design for the cube.

“They’re second to none in Canada, for sure,” said Carpenter on Western University. “So, we’re taking a [watch and learn] sort of role, but they’re also asking for our input on things.”

After Western staff made a February visit to Nunavut, members from both institutes discussed how Arctic College could be more involved moving forward.

Ideas include gathering public opinions on what images to take and when (such as maximum and minimum sea ice, the four seasons or northern lights), and etching symbols into the CubeSat, like syllabics or symbols representing Inuit folklore. There’s also talks of having students in Arctic College’s jewelry and metalwork Program design and create a component of the satellite.

And, until April 12, Nunavummiut can pitch names for the satellite as part of a naming contest.

Carpenter describes the relationship is a good start and says that, as Arctic College contributes more input, the college will become familiar with the process around such projects. With rumours that CSA might hold a second round of CubeSats, that familiarity could prove useful.

Nunavut almost missed its chance with the current program when, in 2017, the territory initially declined to take part for unknown reasons. But when staff from Western University noticed the territory was missing, they reached out.

“One of our co-[principal investigators], Dr. Gordon Osinski, does a lot of research up in the Arctic and in Nunavut,” explained Sabarinathan. “And so he had contacts up in there, and so we discussed this and we were very excited to do something together and so we put forward this project.”

Carpenter hopes that “small successes this time around will give somebody, whoever the space agency calls, the courage to say yes, Nunavut will do this. And do it alone.”

“I don’t think there’s anything in the future that Nunavut’s not going to be able to do.”