Nunavut seamstresses are reviving a skin tent tradition

Pond Inlet elder Rhoda Arnakallak remembers falling asleep in a sealskin tent, lulled by her grandmother’s tales.

But the tent was more than a place to sleep, she said.

“We gathered around as a family, [to] feast on the hunters’ catch and tell stories,” said Arnakallak, through translator Ernest Merkosak, manager for the Nattinnak Visitor’s Center in Pond inlet.

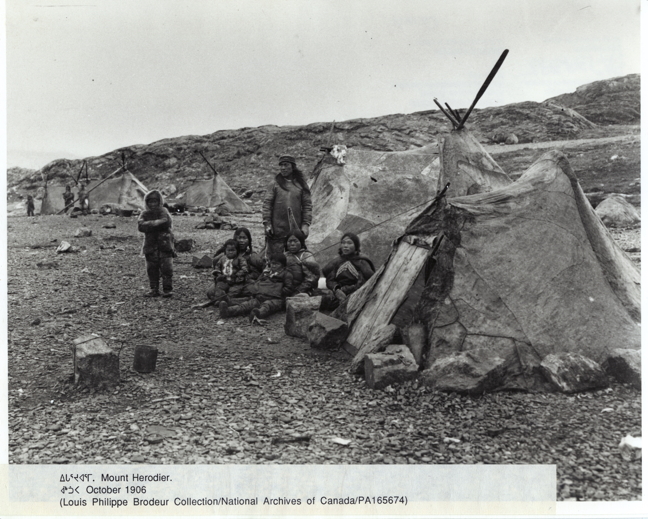

The skin tent, or tupiq, was used by travelling groups from spring until autumn, for hunting or long journeys.

“They are quite easy to set up and take down,” and could be moved quickly when a landscape changed during the spring thaw, said Arnakallak.

The tents were made from the pelts of older seals, which were bigger and less likely to be used for clothing. Seamstresses would scrape the aged fur off the hides, making the tent thin to allow more light to penetrate.

But the skin tents became scarce when Hudson’s Bay Co. traders introduced canvas, a material less valuable and also easier to sew, around the 1940s, said Pond Inlet archivist Philippa Ootoowak.

“They’re not seen anymore here, it’s definitely a thing of the past,” she said.

That is, until this summer.

To keep tents and their tales from being lost forever, six seamstresses are working to create a new sealskin tupiq.

The tent will be set up during the community’s summer tourist season and will sit near to the foundation of an existing traditional sod house, which has been a community attraction for years.

Last summer, the split jawbone of a bowhead whale was positioned in the base of the sod house, to act as a frame.

The sewing group is currently working to craft a sealskin covering for the sod house, which will be stretched over the whale bone. They chose to use sealskin instead of traditional sod, so that the covering can be taken down in winter.

Once the skins, gathered last year, are ready for the sod house, the group will start preparing skins from this year’s hunt to use as a covering for the traditional tupiq.

They hope to have the project finished in time for the first cruise ship, which is expected to arrive on July 28.

“Even if they don’t finish in time for August, the visitors will also be interested to watch and ask questions and see pictures of what they are trying to make,” said Ootoowak. “It’s very neat for even young people in the community to see a sealskin tent being made and learn a bit about their history as well.”

Photos from the Pond Inlet archives show tents used in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but there are also images of recreated tents made in the mid-1980s and 1990s.

One such image shows the Tununiq Theatre Group performing for cruise ship passengers and local people in the early 1990s. The touring group used the tent as a prop for their performances.

While visitors often come to Pond Inlet for business, or to visit the floe edge in the spring, the community sees quite a few cruise ships.

Last year, at least 2,000 tourists from 12 ships visited the community of around 1,600, said the visitor center’s Merkosak. The community is expecting 13 ships this summer, including a second visit from the massive passenger vessel the Crystal Serenity.

When local tour guides show visitors the sod house, they’re often awestruck by the thought of living in one, said Merkosak, who is project lead for the sod house and sealskin tent initiative.

“Some of them compare it to a hobbit’s hut,” he said.

Merkosak also plans to have an inuksuk set up by the site.

For now, the seamstresses will work away at their tasks, scraping, stretching and drying the skins under the midnight sun.

“The final stage is to tenderize the skin to make it flexible,” said Arnakallak, who is transferring her kamik-making skills to the tent and sod house covers.

The only drawback is that there are not enough large or older pelts available in the community, she says, so some pelts being used for the sod house and tent are from younger, smaller seals — good quality skins more often used for kamiks or mittens.

While she finds it difficult to see high quality pelts going toward a tent, “it is more important to preserve this knowledge,” she said.

“The purpose of the project is to recollect the culture, customs and traditions that are fading away. This allows us to connect with each other, young and old,” said Arnakallak. “I guess, in a sense, the traditional tent will continue to tell stories.”