Nunavut should revisit uranium policy, says legislator

“I think we should consult Nunavummiut about whether they support uranium mining or not.”

If you thought the demise of the controversial Kiggavik uranium project in 2016 put a lid on the Nunavut uranium debate, think again.

John Main, the MLA for Arviat North–Whale Cove, said Monday in a member’s statement that it’s time for the Government of Nunavut to take another look at the uranium policy statement it issued in 2012.

“I think we should consult Nunavummiut about whether they support uranium mining or not, and whether we should be talking about this matter, and if Nunavut should have that,” Main said.

Main prefaced his comments by saying his fellow MLAs and his constituents know he’s a strong supporter of mining because of the hundreds of jobs and local contracting opportunities the industry can bring.

But he suggested uranium is different.

“I personally am disconcerted, as it impacts our caribou herds, and in representing my constituents of Whale Cove and Arviat who will be severely impacted when the caribou move because of a mine’s impact,” he said.

Main said the potential impact of uranium mining on caribou is just one of many questions related to the mining of uranium and other radioactive minerals that Nunavummiut should consider.

Policy emerged from Kiggavik controversy

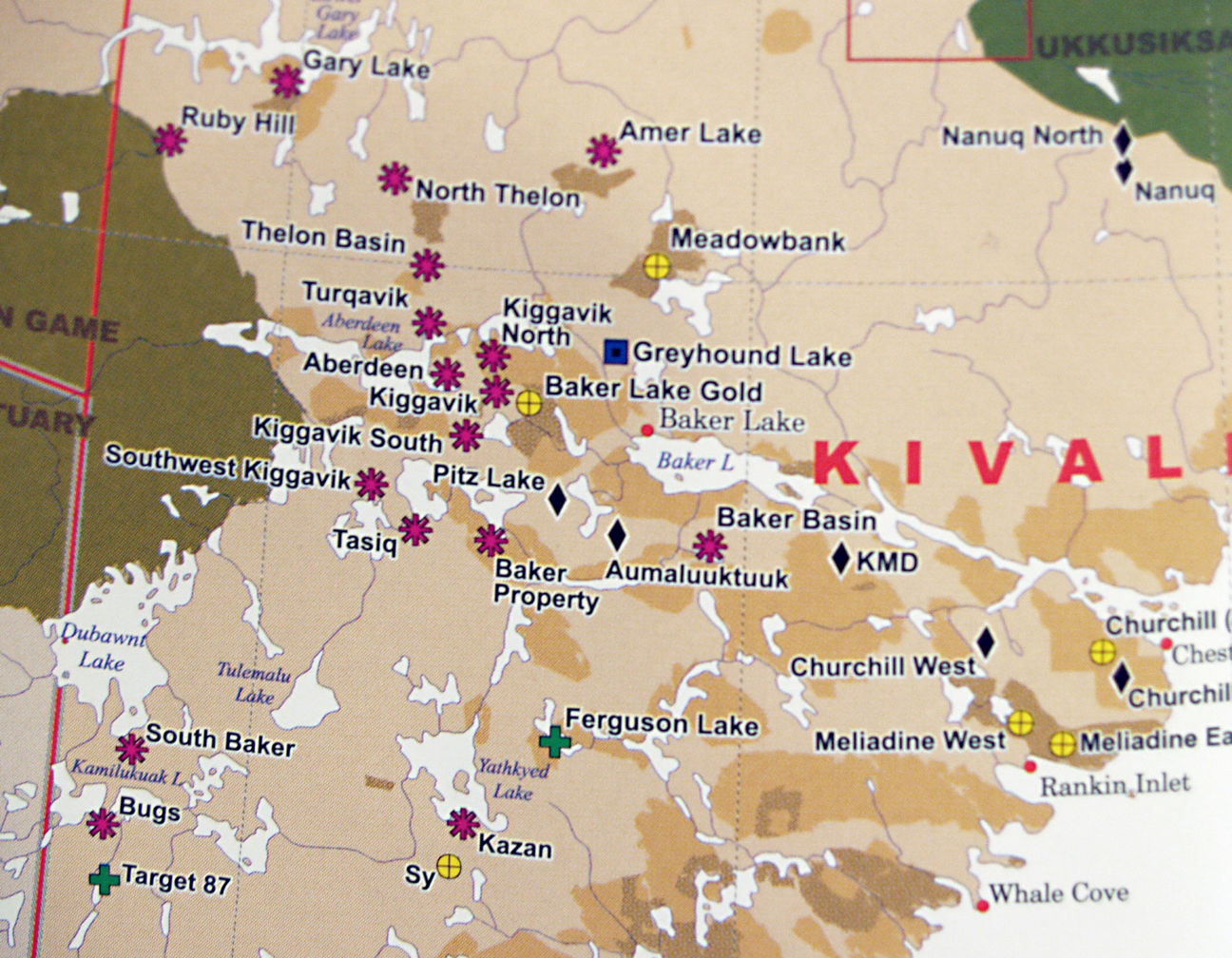

The issue last erupted around 2008, when Areva Resources Canada, in its Kiggavik project, proposed the extraction of uranium from four open pits and one underground site at two spots located about 80 kilometers from Baker Lake.

The GN had no uranium policy at that time.

Around the same time, Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. had adopted its own pro-uranium mining policy in 2006 for Inuit-owned lands. NTI also owned shares in a uranium exploration firm called Kivalliq Energy Ltd., prompting accusations that they had put themselves in a conflict of interest.

And in 2007, the Nunavut Planning Commission amended the Keewatin Regional Land Use Plan to permit uranium mining in the region, and various hamlet councils in the Kivalliq region stepped forward to support the Kiggavik proposal.

But opposition to the project also grew, from the Baker Lake hunters and trappers organization and an activist group called Nunavummiut Makitagunarningit, who put increasing pressure on the GN.

So Eva Aariak, then the Nunavut premier, launched a public consultation process, which included an acrimonious public forum in Iqaluit, aimed at creating a made-in-Nunavut uranium policy.

Aariak’s successor as premier, Peter Taptuna, released the policy statement in August of 2012. It says the GN will support uranium exploration and mining subject to five conditions, including a condition that it must enjoy the support of Nunavummiut.

A plebiscite on uranium?

On that point, Main asked Economic Development Minister David Akeeagok if the GN would ever use a plebiscite to determine whether support for uranium development exists.

Akeeagok said in reply that GN staff would visit communities, and that the territorial government would rely on the Nunavut Impact Review Board’s review processes.

Main said he interprets Akeeagok’s response to mean that it’s very difficult to measure community support.

“I believe that’s the reason why plebiscites exist in terms of determining what the official wish of a community is on a particular issue,” Main said.

He also asked Akeeagok if the GN’s policy extends to the disposal of nuclear waste and radioactive byproducts — an issue the five-point GN policy does not explicitly mention.

Akeeagok replied that “international agreements” are in place that cover the safe disposal of uranium.

After a lengthy environmental and socio-economic assessment, the NIRB eventually recommended, in 2016, that the Kiggavik proposal “not go forward at this time.”

That’s because Areva, hampered by rock-bottom uranium prices in the wake of the Fukushima disaster, couldn’t give regulators a firm start date for the project.

After that, Areva mothballed the Kiggavik property, closed its building in Baker Lake and left the region.