Nunavut’s St. Patrick Bay ice caps are gone, but not forgotten

“It’s kind of a sad little story.”

Nunavut’s St. Patrick Bay ice caps are gone.

Once located on the Hazen Plateau of northeastern Ellesmere Island, the two ice caps were where a 22-year-old grad student named Mark Serreze got his first taste of the Arctic.

“It’s kind of a sad little story,” said Serreze, who’s now the director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

“You think of them as permanent things, an ice cap is an ice cap, and to think that they would die out, it kind of blows me away.”

[Canada’s last fully intact Arctic ice shelf collapses]

Ice caps are glacial ice that show movement, but despite their name, do not always sit on the tops of mountains.

Instead, they are characterized by their size, smaller than an ice sheet but larger than a glacier.

Although it’s hard for Serreze to give the age of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps, he believes that were likely a remnant of the Little Ice Age, which occurred between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries.

“They were fairly young as far as ice bodies or as ice caps go,” said Serreze.

‘A certain irony’

The St. Patrick Bay ice caps provided scientists with a unique opportunity to collect data on how the last ice ages developed.

This is because the ice caps and the land surrounding them were at similar elevations, allowing scientists to place meteorological instruments that measure elements like temperature and the reflectivity of the surface both on the ice and on the land.

“By doing that, we could get this direct view or direct measurement of how these little ice caps were actually affecting the environment,” said Serreze.

Because snow and ice reflect most of the sun’s energy back into space, ice caps affect their own environment by making it a little cooler, says Serreze.

This means that each season more snow and ice are likely to stick around.

The larger the ice surface, the more reflective it is, the cooler the environment becomes and an ice cap can quickly grow into an ice sheet.

In this sense, the story of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps took a wry turn of events, from being used as a prime location to better understand how glacial ice forms to their untimely demise.

“There’s a certain irony there to be sure,” said Serreze.

‘How quickly the environment is changing’

Although Serreze went on to conduct research in other areas after his time on the St. Patrick Bay ice caps, they remained meaningful for him as the place where his career began.

“I always kept my eye on them,” he said.

“A few years ago, it really became apparent that these things were in big trouble.”

[An ice researcher’s memoir follows the unfolding story Arctic melting tells about climate change]

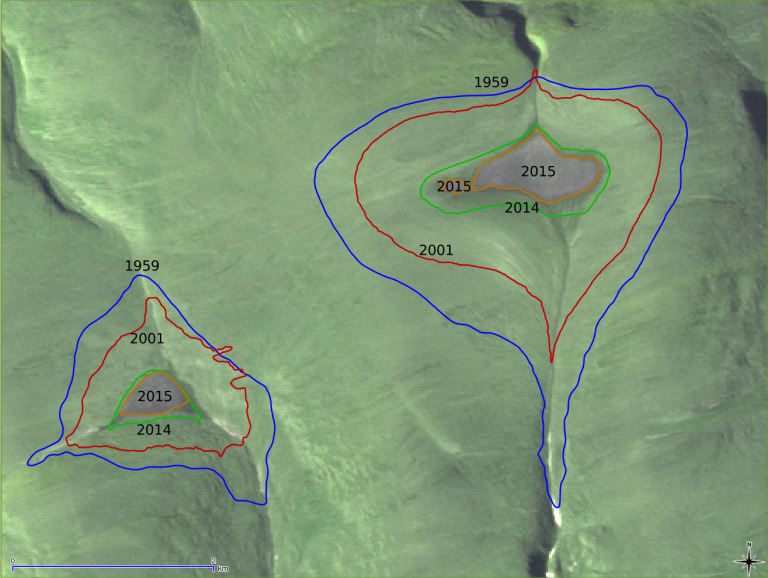

In 2017, Serreze contributed to a paper that predicted that within five years the St. Patrick Bay ice caps would disappear.

“Lo and behold, sure enough, they have,” said Serreze.

“We looked into the satellite data for this summer and they’re gone and they’re probably never coming back.”

While he acknowledges that it’s easy for some to see the demise of two small ice caps as insignificant in the grand scheme of things, Serreze sees it differently.

“These things really are indicators of how quickly the environment is changing up there,” he said.

Around the same time, Serreze also worked on the Murray and Simmons ice caps, which are south of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps but still on northeastern Ellesmere Island.

While they are still around, that may not be the case for much longer.

“They’re bigger to start with and they’re a little higher in elevation, and as you go higher in elevation, it gets cooler and cooler and cooler, so they’re hanging on a little bit better,” said Serreze.

“But they’re on their way out. I’d say a decade and they’re gone.”

While the disappearance of the St. Patrick Bay ice caps is a loss for Serreze, Nunavut and the planet as a whole, there may be a glimmer of hope.

“I think we’ve reached a turning point, said Serreze.

“Climate change is here and there is no escaping that the cause is us, the pandemic has exposed our vulnerabilities and we are finally facing our long history of racial injustice. The first key step in moving forward is getting past denial and I think we are there.”