On Alaska’s St. George Island, a mayor fights for fur seals — and a new future

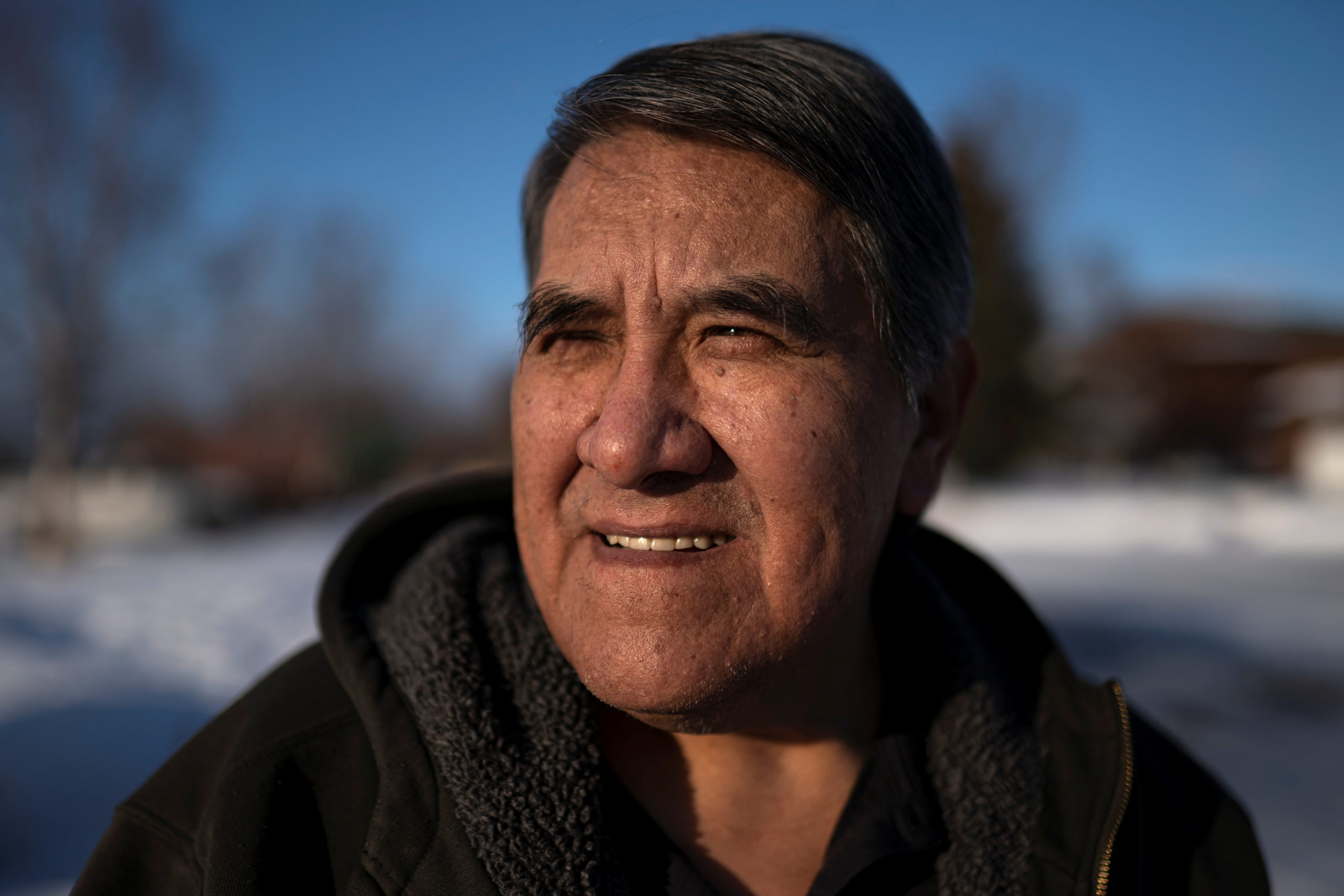

Patrick Pletnikoff hopes a new marine sanctuary could save both the island's iconic species, and its economic vitality.

ST. GEORGE ISLAND, Alaska — Fifty years ago, Patrick Pletnikoff spent his summers stripping blubber from the carcasses of seals clubbed to death in Alaska’s annual harvest, competing with other young men to show who wielded the fastest blade.

Now he’s fighting for a bigger prize: to transform his native St. George Island’s fortunes and protect dwindling colonies of northern fur seals by creating Alaska’s first marine sanctuary in the surrounding waters — a move that would empower local people to limit fishing for the seals’ prey.

Commercial sealing was once the lifeblood of St. George, a treeless speck of volcanic rock in the Northern Bering Sea, far from the U.S. mainland. But the Indigenous Unangan community has struggled to find a new niche in the decades since the trade was banned, and there are now less than 60 inhabitants left.

As the long-serving mayor, Pletnikoff has spent years lobbying the federal government to add St. George to the network of 15 U.S. marine sanctuaries, hoping that a designation will kick-start a new “conservation economy” based on eco-tourism, scientific research and sustainable fishing.

With President Joe Biden pledging to expand ocean protections, Pletnikoff believes his dream of placing his fog-shrouded home on a par with sanctuaries such as California’s Monterey Bay or the Florida Keys may finally be within reach.

“It could be a new beginning,” Pletnikoff, 73, said of his plan for St. George, which along with neighboring St. Paul is sometimes referred to as the “Galapagos of the north” for its role as a haven for wildlife in the northern Pacific.

“We’ll look at this holistically, and try to understand what our responsibilities are: Not only to ourselves, but to our environment and the animal kingdom as well,” he said.

With climate change also affecting the surrounding Bering Sea, where sea ice in recent winters has hit its lowest level in millennia, advocates say the proposal could ease pressure on seals by allowing islanders to regulate industrial trawling of the walleye pollock that the species depends upon for food.

Establishing a sanctuary could also help right historic wrongs, Pletnikoff added.

Generations of his Unangan ancestors worked in harsh conditions in the sealing trade, run first by Russian explorers and then the U.S. government. The lingering sense of exploitation is evoked in a contemporary folk song called “Slaves of the Harvest.”

Now, the National Marine Sanctuaries program, run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, aims to give local people more autonomy to manage designated waters — including powers to control fishing.

With the Bering Sea considered one of the most lucrative and rigorously-monitored fisheries in the world, plied by vessels sailing 2,000 miles from Seattle to drag their nets off St. George, fishermen are wary.

The industry says the area is already sustainably managed by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, an advisory body that sets quotas in consultation with fishermen, Alaska communities and scientists.

“Limiting or taking their regulatory power away in an area with no scientifically based challenges is a solution in search of a problem,” said Gavin Gibbons, spokesman for the National Fisheries Institute industry group.

Tribes ‘in the driving seat’

As a boy, Pletnikoff would hike with his father across the island’s landscape, learning to hunt and fish. His eyes tear up at the thought that his people’s knowledge of St. George’s seals, Steller sea lions and seabirds could be lost.

Nevertheless, on one level, the mayor has succeeded in bringing sanctuary status closer.

In December, a congressional committee requested NOAA begin designating five sanctuary nominations it already had accepted for formal consideration, including the proposal from St. George which Pletnikoff submitted in October, 2016.

In April, Biden proposed a record $6.9 billion budget for NOAA, with funds earmarked for the designations that also include a proposed Chumash Heritage sanctuary off California, Pennsylvania’s Lake Erie Quadrangle, the Atlantic’s Hudson Canyon and the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific.

Biden’s emphasis on Indigenous stewardship in his goal of protecting 30 percent of U.S. land and sea by 2030 could also play in Pletnikoff’s favor.

“More and more, federal officials are recognizing that tribes need to be more in the driving seat when it comes to land or environmental issues,” said Raina Thiele, an Alaska Native who co-chairs Biden’s Native American Policy Committee.

But establishing a sanctuary can take years, as NOAA launches rounds of public consultation, develops management plans and seeks approvals from politicians.

With St. George’s proposal lacking a champion in Alaska’s state government or its Congressional delegation, which is comprised of Republicans, there is no guarantee it will move forward any time soon.

[Biden’s day one orders revived key protections in Alaska’s northern Bering Sea]

Lashed by storms and a corrosive sea breeze, the dilapidated facades of the island’s houses suggest time may be short for the mayor to reverse the decline.

Nearby, spectacular thousand-foot cliffs provide nesting sites for the bulk of the world’s population of red-legged kittiwakes, a species in the gull family, while auklets, puffins and guillemots also thrive.

But it is the northern fur seals performing lazy barrel rolls in the surf, or playfully grappling each other with their flippers, that are closest to Pletnikoff’s heart.

Legacy of servitude

St. George takes its name from a Russian sloop that made landfall on the then-uninhabited island in June, 1786 by following seals through fog.

The Russians lost little time in rounding up Unangan people from the Aleutian island chain some 220 miles (355 kilometers) to the south to harvest and skin the seals. For much of the 19th century, the activity was Alaska’s most profitable industry.

Passing under U.S. control following the purchase of Alaska in 1867, commercial sealing remained the foundation of the local economy until it was banned in St. George and St. Paul, the main islands in the Pribilof chain, in 1973 and 1984 respectively.

The trade cast a long shadow: Federal overseers once dictated almost every aspect of life on the islands, including whom Unangan workers could marry, historians say.

The system came to national attention only after more than 800 Pribilof and Aleutian islanders were interned on the Alaska mainland in terrible conditions during World War Two. Several of Pletnikoff’s family members were among the 10 percent who died.

Since sealing has wound down, St. George’s population has fallen by about 75 percent from its peak of 250 in the early 1960s. Four years ago, the only school closed.

Meanwhile, northern fur seals have declined. On St. George and St. Paul, their main breeding grounds, numbers have fallen to about 459,000 from 2.1 million in the 1950s, according to NOAA estimates.

On the uninhabited Bogoslof Island to the south, however, northern fur seal numbers have increased from almost none 30 years ago to about 161,000.

Researchers have spent years considering possible factors at play: from disturbance by ships and entanglement in fishing gear to pollution, predation by killer whales and climate change.

In December, an analysis of northern fur seal diets published in Frontiers in Marine Science found that previous studies may have “vastly underestimated” the amount of commercially-valuable walleye pollock consumed by the species.

Although scientists do not know how much impact fishing might be having on seal numbers today, Pletnikoff saw the paper as vindication of what he had long suspected: large trawlers are competing directly for the animals’ prey.

[A radical transformation of the Pacific Arctic appears to be underway, a new study finds]

Not everyone believes that a sanctuary would bring tangible benefits.

Some question how many tourists would risk being stranded when fog grounds flights. Others fear changes to today’s management system might hamper prospects for generating local fishing jobs.

“The benefits of a sanctuary beyond the conservation measures and public forum that are already supported through this existing regulatory framework are unclear,” said Luke Fanning, chief executive of the non-profit Aleutian Pribilof Island Community Development Association, which supports a small-scale halibut fishing program in St. George.

Nevertheless, with American and European seabird biologists who have fond memories of field trips to St. George backing his plan, Pletnikoff hopes a sanctuary designation could spur the creation of a permanent research station.

His vision: to combine modern science with ancestral knowledge to find ways to buffer seals and other wildlife from the challenges ahead.

“Generations of Unangan people, including my younger brothers and sisters, grew up with knowing nothing more than fur seals and seabirds — and knowing our environment,” he said. “We don’t want to see that destroyed.”

Nathan Howard Reported from St. George and Matthew Green reported from London; additional reporting by Yereth Rosen in Anchorage and Valerie Volcovici in Washington; writing by Matthew Green; Editing by Mike Collett-White.