One of the first scientists to document sea ice retreat puts four decades of experience into a book

It was the 1970s. The girls in the band were topless and, for the pilots, a night out at The Flyers’ Club, in Gander, Newfoundland, often lasted until late. The pilots, though, were always ready to fly each morning, over the sea ice in the northernmost stretches of the Atlantic. It was on those flights that a young Peter Wadhams noticed from his observation window at the top of the plane’s fuselage that something was happening below. The observations made him one of the first scientists to document the sea ice retreat.

Today, Wadhams is one of the world’s leading experts on polar sea ice, the mechanics that drive its disappearance and the consequences of its retreat on our climate (of which there are many, since with less ice, less of the sun’s energy is reflected back into space).

Between 1987 and 1992, Wadhams headed the UK-based Scott Polar Research Institute, one of the world’s leading polar-research institutions. After which he served for 13 years as a professor of ocean physics at Cambridge. In “A Farewell to Ice – a report from the Arctic,” published on Sept. 1, he shares insights gained over more than four decades of Arctic and Antarctic expeditions and his somewhat pessimistic conclusions.

Wadhams accuses the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (and by extension most of the world’s decision makers) of massively underestimating the pace at which sea ice is receding, and the global impact this will have in the form of droughts, storms, flooding, famine and general destruction.

To support his gloomy outlook, Wadhams presents his own findings and those of scores of other polar researchers. Among his more dramatic predictions, he expects that the first ice-free summer at the North Pole could occur as early as 2017, not 2050, as the IPCC expects. The IPCC, he believes, is “consciously ignoring the observational data in favour of accepting models that have already shown themselves to be false.”

A Farewell to Ice provides a thorough and timely overview of Peter Wadhams’s own research and his analysis of vast amounts of other current polar research into ice. We’re also provided with a fleeting account of a dramatic event on one of his expeditions under the Arctic ice aboard a British nuclear-powered submarine. A subsea explosion nearly led to the entire boat being lost. Two of the crew were killed in the incident.

Unfortunately, such accounts of Wadhams’s work in the field are sporadic and terse. The title of his book plays on Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms,” but the drama Wadhams depicts, is not his own but the planet’s.

Wadhams presents his science eloquently and in terms that are easily grasped by the reader, even in the passages that spare few technical details. He takes particular care to explain how melting sea ice perpetuates a number of feedback loops, in which the impacts caused by the lack of ice lead to further sea-ice loss.

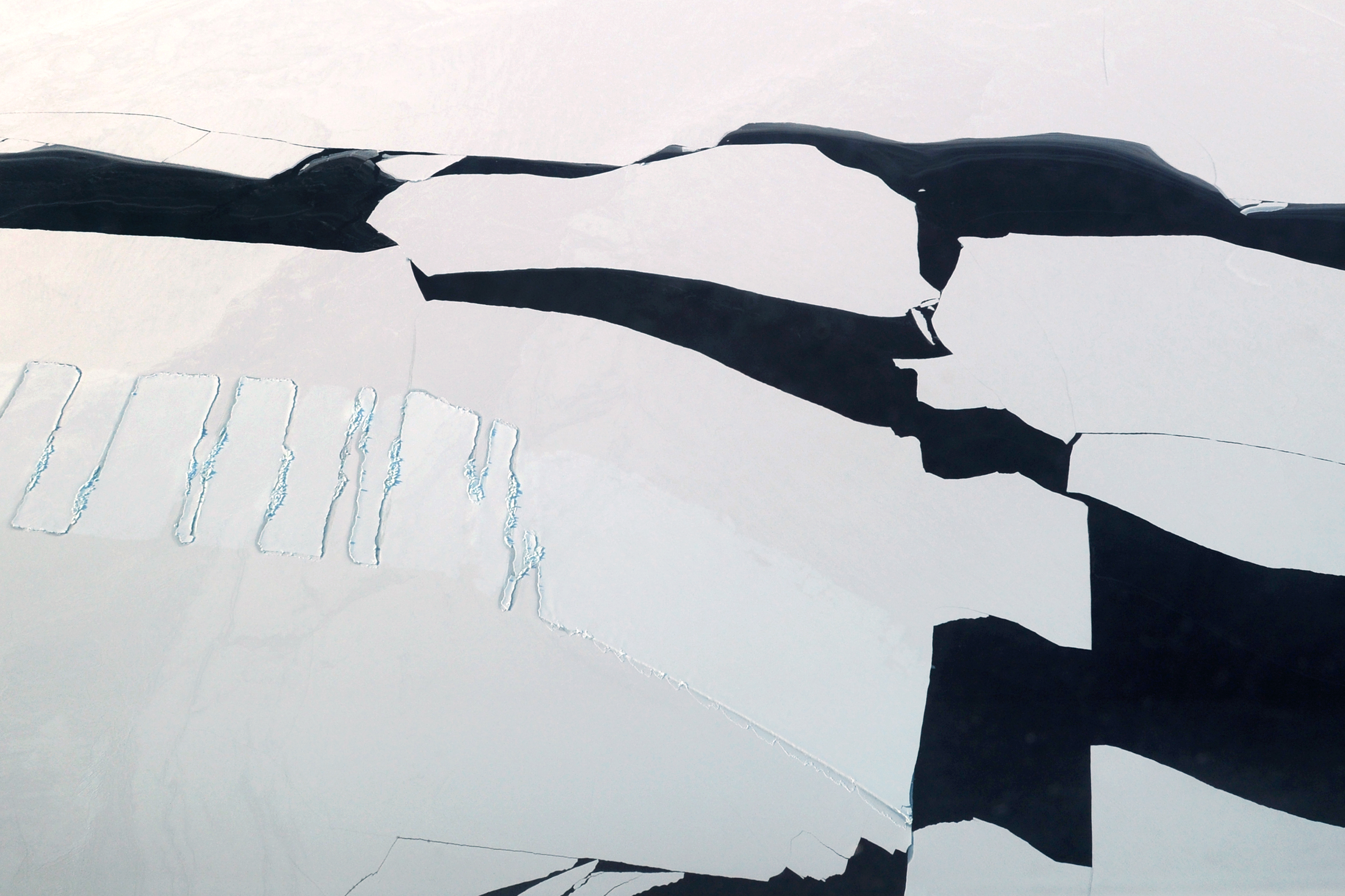

One significant feedback loop arises when the disappearance of ice allows for larger waves to develop in the Arctic Ocean. With less ice to provide a protective covering on the ocean, the polar winds will whip up more, larger waves. These will hit the remaining sea ice, break it and cause it to melt faster, leaving behind more open water allowing for still larger waves in a self-perpetuating cycle.

Wadhams lays out no less than 10 such feedbacks, a process he labels “runaway warming.” He credits Mark Serreze, head of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, in Colorado, with the term the “Arctic death spiral.”

Wadhams devotes a full chapter to current research into the release of methane from the floor of the Arctic Ocean and from the region’s permafrost. Once again, he accuses the IPCC for underestimating the dangers. Water temperatures have, for the first time in thousands of years, risen to above 0°C at the ocean floor in parts of the Arctic. This phenomenon has gained speed since 2005, when, for the first time, large parts of the Arctic Ocean were free of ice. One of these areas was the East Siberian Sea, which in many areas is less than 40 meters deep.

When water temperatures rise to above freezing at the ocean floor, the sea bed begins to thaw. As it does, large volumes of methane are released and percolate to the surface. “A Farewell to Ice” includes a rare picture of these subsea clouds of methane taken by a Russian scientist, and Wadhams is clearly worried.

As a greenhouse gas, methane is far more powerful than carbon dioxide, and the threat is now so grave that, in Wadhams’s opinion, immediate action is necessary. The oil industry has offered to drill horizontal pockets under the ocean floor where methane can be contained and then pumped to the surface and burnt off, and Wadhams argues that the time has come for this type of geoengineering. “It would be ironic if the oil industry saved the world through its advanced technology, but I am sure that God would raise a smile,” Wadhams writes.

Wadhams is in his element when he presents his wealth of scientific knowledge of sea ice and the processes involved with its disappearance. His editors could have have helped by pushing two introductory and rather technical chapters further back and by weeding out in Wadhams more general commentary about the state of the planet. But when it comes to explaining the retreat of polar ice, the science behind it and how it relates to our climate, “A Farewell to Ice” serves a hugely important task and sets a high standard for future books on the topic to meet.

A Farewell to Ice – a report from the Arctic, By Peter Wadhams: Allen Line/Penguin, 239 pages, illustrated, £20

Martin Breum is a Danish journalist who has written extensively about Arctic issues, including most recently “The Greenland Dilemma.” He is an occasional contributor to The Arctic Journal, where this review first appeared.