Permafrost thaw will force Greenland’s Kangerlussuaq Airport to close to most commercial traffic in 2024

Permafrost under the runway at Greenland's main international hub is warming and thawing, causing the runway to subside and crack.

Kangerlussuaq Airport is Greenland’s main hub for international and domestic flights with 250,000 annual passengers, of which between 80 and 90 percent transfer to different flights. Thawing permafrost has resulted in technical failures of the pavement requiring either costly and ongoing repairs and maintenance or a shortening of the runway, which would impact its suitability for large commercial airliners.

While it has not yet been determined to what extent the airport will be used for commercial traffic after 2024, international traffic and most Air Greenland flights will be relocated to yet-to-be-built runways at the airport of the capital Nuuk in the south and the tourist destination Ilulissat to the north.

“The current status is to partly close the airport for Air Greenland scheduled traffic during the summer of 2024. It is now agreed and confirmed by the Greenlandic and Danish Government, that the airport will remain open […] mainly for the future use by the Royal Danish Air Force and commercial traffic. The extent and use of commercial traffic is not yet determined,” explains Peter Høgh, the International Airport Manager of Mittarfeqarfiit, the company that manages Greenland’s Airports.

A history of runway damage

Damage to the runway was first documented in 1973 when the pavement at the western threshold had settled up to 30 centimeters resulting in local repairs. More extensive excavation and replacements occurred in 1988/89 when the entire runway was repaved. However, the runway continued to settle and by 2006 a 400-meter-long section had settled unevenly by up to 40 centimeters. Further studies conducted in 2013 measured settling of 52 centimeters leaving scientists to conclude that the western part of the runway sinks by 2.6 centimeters per year.

Greenland’s government has considered a number of options following various expert studies and reports, including downgrading the Kangerlussuaq to a heliport, shortening the runway, or maintaining the current situation. All options come with substantial costs.

Permafrost threatens Arctic infrastructure

Greenland’s largest airport is just one of a growing list of infrastructure that is becoming susceptible to thawing soil. Permafrost is ground that is frozen year-round for at least two years. With rising temperatures across the Arctic more and more permafrost is susceptible to melting turning solid frozen earth into mud. This can result in destructive failures for any structure erected on top of it.

Recent studies on the matter confirm that 70 percent of the Arctic’s roads, buildings, and airports have a high potential to be affected by thawing ground over the next 30 years. A 2018 study by the University of Alaska Fairbanks concluded that three-quarters of the Arctic population, about 3.6 million people, are located in areas with a high potential for thawing of permafrost. Even just across the “high hazard” zone more than 36,000 buildings, 13,000 kilometers (more than 8,000 miles) of roads and 100 airports face a very high risk of damage by 2050.

The effects of permafrost melt are not limited to road and housing infrastructure but also affect major industrial developments, such as oil and gas projects in Russia’s Yamal region, as well as Alaska’s trans-Alaska pipeline.

“We show that nearly four million people and 70 percent of current infrastructure in the permafrost domain are in areas with high potential for thaw of near-surface permafrost. Our results demonstrate that one-third of pan-Arctic infrastructure and 45 percent of the hydrocarbon extraction fields in the Russian Arctic are in regions where thaw-related ground instability can cause severe damage to the built environment,” explains Vladimir Romanovsky, a scientist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute.

Finding a suitable alternative for Kangerlussuaq

Kangerlussuaq’s situation is unique among the country’s airports explains Høgh.

“The only other airport with similar problems is Thule Air Base, the American air base in the far north, but closed for civil/commercial traffic – and information.”

Kangerlussuaq’s facilities face an extreme range of temperatures ranging from as low as minus 45 degrees Celsius to as high as 25 degrees Celsius.

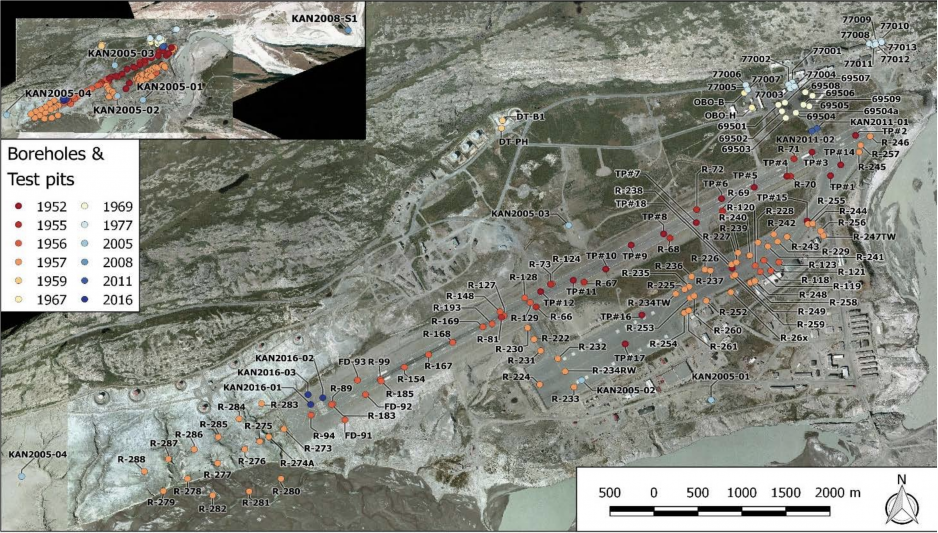

Experts have continuously studied the runway with the use of boreholes to survey any damage. Latest studies conclude that ongoing settling is likely caused by ice-rich deposits under the western part of the runway and by the use of non-frost susceptible material during the construction of the embankment. The pavement also faces cracking due to the “large thermal variance” as joints were inadequately sealed.

The closure of Kangerlussuaq Airport to most commercial traffic within five years represents significant logistical challenges. While the airport does not represent the final stop for the vast majority of passengers, it serves as the key distribution hub for all incoming visitors. Kangerlussuaq’s stable arid continental climate limits the airport’s closings to a few days a year and in practice careful planning of flights has allowed for “close to 100 percent regularity.” In contrast, Nuuk further south is known for notoriously bad weather conditions and the north-south orientation of the current runway results in frequent crosswinds requiring airplanes to divert to alternate airports.

Kangerlussuaq Airport is just one of many examples that the challenges related to melting permafrost will grow larger in the years to come.

“Much more needs to be done to prepare [Arctic populations] for the adverse consequences of coming changes in permafrost and climate,” concludes Romanovsky.