Phytoplankton blooms hint at changing Arctic waters

On the surface, two recent NASA images depict common summer phytoplankton blooms. But signs of climate degradation are in the details.

During the spring and summer in the Arctic Ocean, various types of phytoplankton show up in abundance. This happens when ice cover recedes, exposing these floating plant-like organisms that, like plants on land, need sunlight and nutrients to thrive to the ample sunlight that causes their numbers to explode.

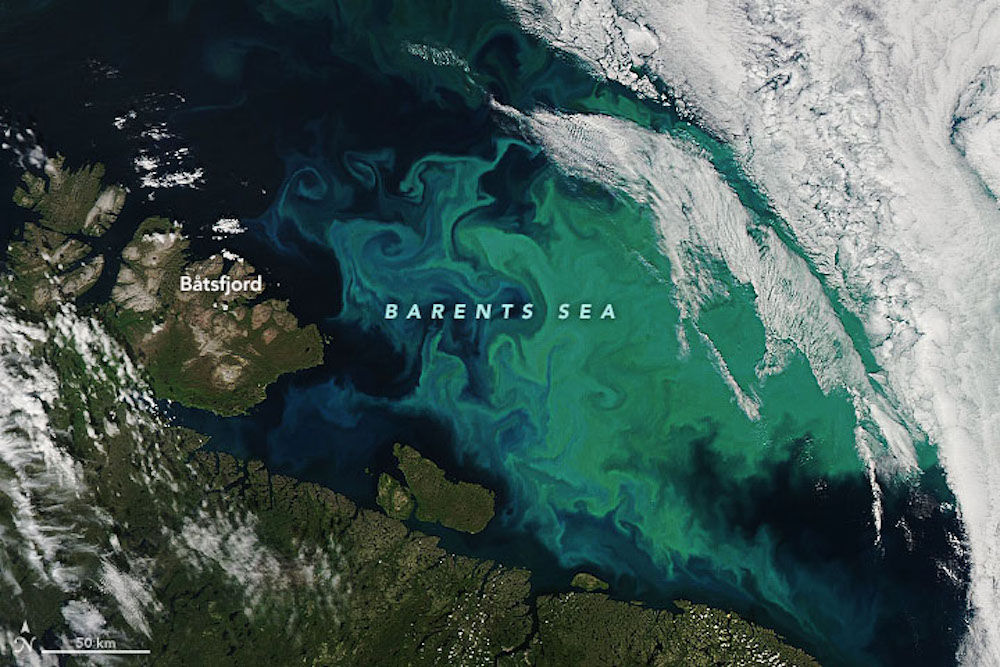

At times, these blooms can be so large that they are visible from space. Two composite images made available by NASA, America’s space agency, during the past month have shown this occurring in mesmerising detail. But they also hint at something less appealing: change brought on by a warming marine environment.

For example, the image above, taken of the Barents Sea on July 15, is odd in that the bloom is two-toned. Typically, various types of phytoplankton bloom at different times. This is because different species thrive under different conditions, causing the blooms that mark their high points to occur in sequence.

In the Barents Sea, the blooms that occur in spring and early summer are typically composed of diatoms, a microscopic form of algae with silica shells and ample chlorophyll, which makes them appear green in satellite images.

[How Barents Sea ice loss contributed to extreme winter conditions in Europe]

Starting in late July, the water becomes warmer and well-defined layers form. This change promotes the rise of coccolithophores, a type of phytoplankton that turns the water milky whitish green in satellite imagery due to their calcium carbonate shells.

Such concurrent blooms have been observed before, according Andrew Orkney, of the University of Oxford. And while this may be the case here as well, Orkney, the author of a paper on phytoplankton in the Barents, reckons that the color likely results from a coccolithophore bloom occurring in waters rich in what is known as colored dissolved organic matter, which can make seawater appear anywhere from green to yellow-green to brown.

Identifying just what is occurring in the image would require samples of the water to be taken. But, regardless of what is currently happening, recent research has found that coccolithophore blooms are occupying increasingly more space in the Barents Sea. Between 1998 and 2016, coccolithophore summer blooms have expanded poleward and their surface area in the Barents Sea has doubled.

[The Arctic Ocean is becoming more like the Atlantic and Pacific, studies say]

Such changes could have implications for Arctic marine food webs and geochemical cycles. Coccolithophores and other type of phytoplankton are a primary food source for small zooplankton and fish. They are also critical to the global carbon cycle and key producers of Earth’s oxygen.

Similar findings were reported in a recent paper concluding that the rate of growth of phytoplankton biomass across the Arctic Ocean increased by 57 percent between 1998 and 2018. This is due to both the increasing frequency of blooms, and their tendency to last longer. In all, scientists calculate that Arctic phytoplankton blooms account for about 40 percent of the region’s annual net primary production, a measure of how much carbon dioxide vegetation consumes.

In places such as the waters around Greenland, which are fed during the summer months by the fresh water of melting glaciers, such a conclusion would seem to overturn a previous assumption that increasing glacial melting in might lead to fewer nutrients and blooms.

That the prevailing thinking might not actually be the case was first posited in 2017, when scientists noted a correlation between phytoplankton blooms and pulses of fresh water into the seas surrounding Greenland during the summer.

[Arctic sea ice algae need less light to grow than researchers thought. Here’s why that matters]

The theory now is that the flow of fresh meltwater from the icecap out to sea carries iron, silicate, phosphorous and other nutrients that phytoplankton subsist on. This appears to be what is happening in the image above, showing the coast off Nuuk on July 8.

It depicts Ameralik Fjord and other inlets, stained chalky tan and gray by sediments the powdery remains of rock that has been crushed by the immense weight of the icecap moving over it. Known as glacial flour, it gets washed out with meltwater into Baffin Bay, the Davis Strait and the Labrador Sea, where the light green swirls in the image indicate the presence of phytoplankton in summer bloom.