Post-Brexit, Scotland looks toward a more Arctic future

Is Scotland the newest Arctic nation?

As interest in the High North heats up, places far from the 66th parallel have sought to position themselves as Arctic players.

Twelve nations, as far south as Singapore (a scant single degree north of the Equator), have been granted observer status at the Arctic Council, and other regions, from the Baltic to the U.S. state of Maine, have shown an interest in the region.

[How Maine is turning itself into an Arctic player]

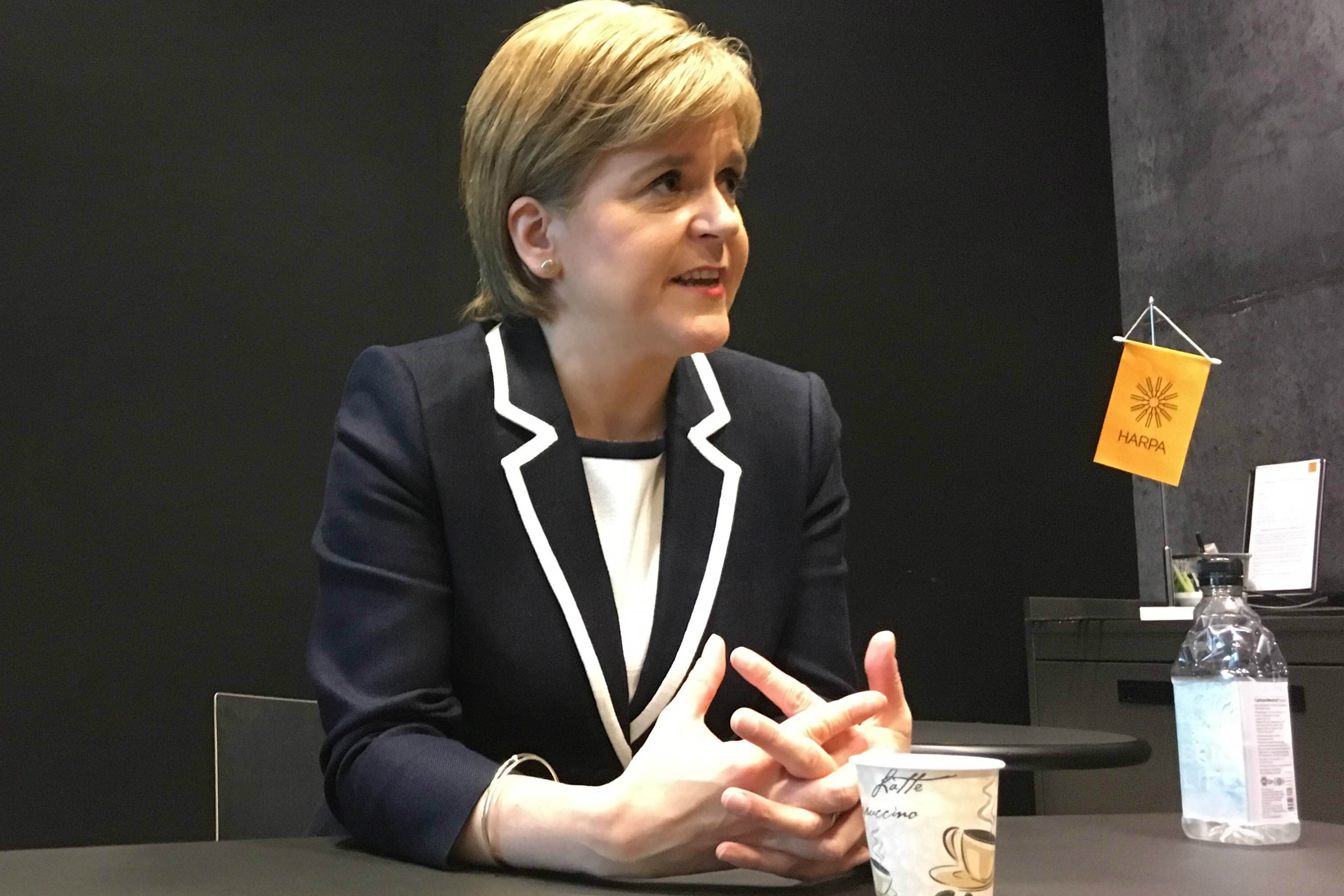

But during a keynote address Friday at an international Arctic conference in Reykjavik, Iceland, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon staked out a special place for her nation as the nearest of near-Arctic states.

“The north of Scotland is actually geographically closer to the Arctic than to London,” Sturgeon said.

The remarks drew a scattering of knowing laughter from the international audience. They come as Scotland pivots to the north in the wake of Brexit, the United Kingdom’s June referendum vote to leave the European Union—a move strongly opposed in Scotland and one which has revived talks of another Scottish independence vote. (To questions on whether such a vote might be held, Sturgeon would only say a decision would come “when we think the time is right.”)

Scotland has sought to collaborate more closely with the Nordic Council, an inter-parliamentary gathering of the five Nordic nations and several territories.

And Scots opposed to Brexit but not eager for another independence vote have found in the Arctic one potential solution to their political future. In the so-called “reverse Greenland” scenario, Scotland would remain in the EU, while England and Wales exit. The move hearkens back to Greenland’s departure, in 1985, from the EU’s predecessor organization while remaining in the Kingdom of Denmark.

But while Sturgeon talked up Scotland’s historic cultural and trade ties with Nordic—and Arctic—nations of the North Atlantic, she also downplayed the role of Brexit in Scotland’s fresh Arctic interest.

“I don’t think it’s been sudden,” she said.

Scotland’s long been engaged with climate change, in the Arctic and elsewhere, she said, and is a world leader in research into sustainable energy sources, such as wind and tidal, that have shown promise in the region.

And a Scotland oriented to the north no longer sees itself as a nation on Europe’s periphery. Seen from the Arctic, Sturgeon said, “We’re the gateway to Europe.”