Quebec’s anti-racism task force is flawed without Inuit voices, says Makivik

Makivik Corp. calls on province to reform Nunavik’s justice and policing systems.

The Quebec government has announced the creation of a task force to counter racism in the province, and Makivik Corp. has a suggestion for where to start — Nunavik’s justice system.

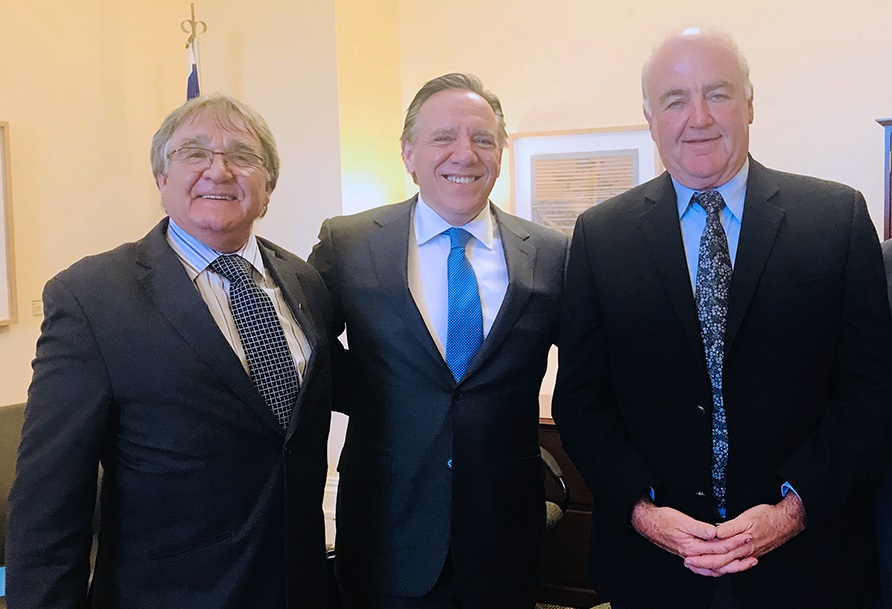

Although Quebec Premier François Legault has denied there is systemic racism in the province, his government announced on Monday, June 15, the creation of a new “action group” tasked with coming up with ways to combat racism.

The group is composed of seven Coalition Avenir Québec ministers and MNAs, including Lionel Carmant, Quebec’s minister of health and social services; Minister of Indigenous Affairs Sylvie D’Amours; and Ungava MNA Denis Lamothe, who is Nunavik’s representative in Quebec’s legislature.

Legault has asked the group to look at priority areas, such as public security, justice, education, housing and employment in Quebec, and to consider the specific realities of racialized and Indigenous communities.

But Makivik Corp., which represents Inuit in Nunavik, says the group is already flawed without the representation of Inuit or other Indigenous groups.

“The protests taking place around the world highlighting systemic racism inside the justice systems is alive and well in Nunavik and it sickens me,” said Makivik President Charlie Watt in a June 17 statement.

“A systematic overhaul of the administration of the justice system and policing is long overdue. Report after report has called for an overhaul. Study after study has highlighted the deficiencies in both systems and Inuit are suffering discrimination from both systems in all levels from education to health care and the administration of communities.”

Among its demands, Makivik said that Nunavik in particular should have an Inuk chief of the Kativik Regional Police Force.

Makivik also called for a revamp of the region’s youth protection services to reflect Inuit culture and a justice system that is based in the region, rather than one that relies on a circuit court and southern lawyers.

Makivik pointed to a handful of reports and inquiries that have already exposed issues of racism and inequity in Nunavik and within other racialized and Indigenous communities throughout Quebec.

Just last year, Quebec’s Viens Commission — which looked at what barriers Indigenous people face when accessing certain government services — released its findings, along with 142 recommendations.

“The pandemic, and the demonstrations related to systemic racism within police forces, are bringing these issues to the forefront, and we want to work with you to get to the bottom of the problems of policing and the justice system in Nunavik,” Watt said, in a comment directed to the government.

For its part, the task force has been mandated to come up with a series of recommendations to be tabled this fall.

“We were all deeply touched by what happened in the United States,” said Premier Legault earlier this week, referring to incidents of police brutality against Black Americans and the anti-racism protests that have followed.

“We must avoid importing this climate of confrontation here. The majority of Quebecers are not racist. But there is racism in Quebec. We must no longer tolerate acts of racism in Quebec. We must take action.”